On a cold, January afternoon in 2019, curator and art consultant Lele Barnett walked into a stately brick house in Edmonds and discovered what must have been one of the largest stashes of art she had ever seen: hundreds of paintings, calligraphy drawings and sketches stacked on top of each other, hanging on the walls, lying in flat filing cabinets — all made over the past 40 years by Victor Kai Wang.

“It was like stumbling upon buried treasure,” Barnett recalls. With her decades of experience placing art in private and corporate collections, she could easily imagine some of these swirling, semiabstract landscape paintings on the walls of a major museum. But most of the works had never left Wang’s home.

The Chinese American artist, now in his late 80s, lived much of his adult life in a house on Seattle’s Beacon Hill. More recently, he has been based in a mansion (a gift from his children) on the Edmonds waterfront. But besides a few showings at an antique shop in Bellevue in the 1990s, he had never exhibited his work in an art gallery or museum. Barnett decided right there and then: “It needs to be shown.”

This week, Barnett made good on that promise. About a dozen of Wang’s paintings are hanging in an upstairs exhibit space at the Wing Luke Museum, part of the group show Reorient: Journeys Through Art and Healing, opening June 10 (running through May 14, 2023).

The show, curated by Barnett, unites Wang’s work with that of three other contemporary artists based in the American West. All of the artists have something in common, Barnett says: experimenting with nontraditional art materials — clothing, pumice, tree branches, marking-pen ink — to transmute personal stories of immigration and trauma into joy.

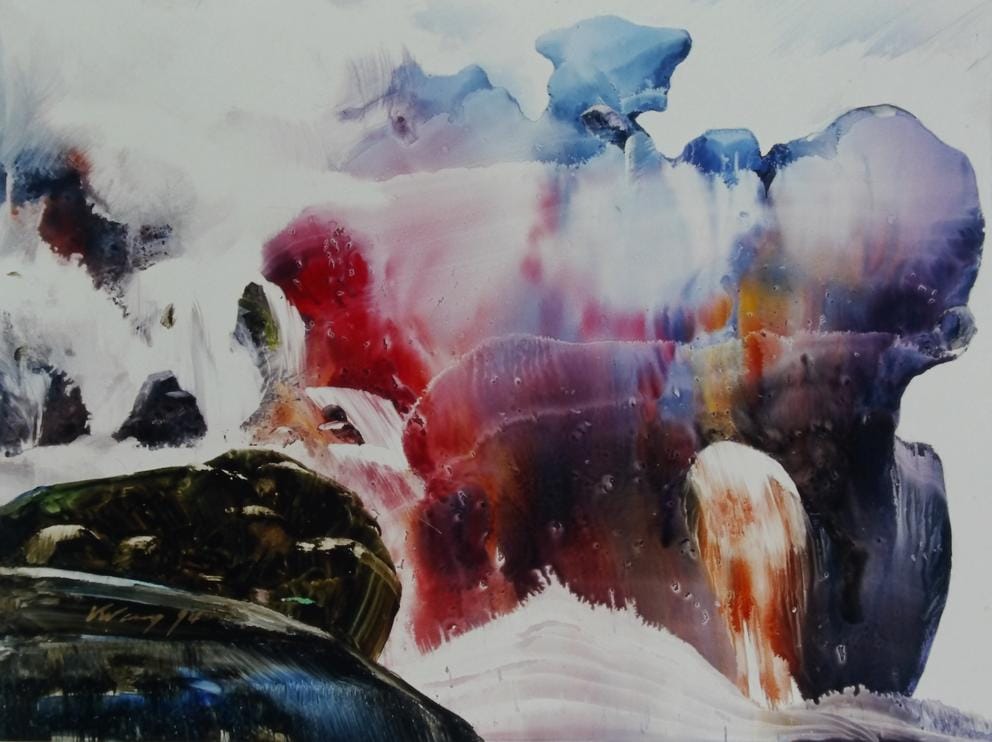

“Song of Falls,” painted by Victor Kai Wang in 1992. (Victor Kai Wang)

When Wang arrived in the U.S. from China in 1980, he faced challenging years as a newcomer. But art proved a respite, says Barnett, who spoke extensively with Wang and his children about his experience.

She sees a similar “reorientation to joy” in the work of the others featured in this show: Seattle artist Tuan Nguyen, who fled Vietnam with his parents; Jean Isamu Nagai, a Japanese American born in Washington state and now based in Los Angeles; and Guyana-born, Denver-based Suchitra Mattai, whose art often explores the journey of her Indian ancestors, who worked as indentured laborers on sugar plantations in colonial Guyana.

“All of these artists felt disoriented,” Barnett says, explaining the title of the show, “being in this new surrounding or trying to fit in with these other kids — and then [found] art to help them reorient themselves.”

Nguyen’s surreal wall-hangings, Mattai’s fabric installations and Nagai’s pointillist paintings have been exhibited relatively widely. But even the most in-the-know art connoisseurs have probably never heard of Victor Kai Wang. Until early 2019, neither had Barnett. Wang doesn’t have a website, and barely any internet presence at all. But an email from Wang’s sons had piqued her curiosity.

At his Edmonds home, when she flipped through his paintings — some up to 5-by-7 feet — Barnett’s jaw dropped. Amid the imagery, she could discern the “scholar’s rocks,” towering mountains, jagged cliffs and waterfalls of the traditional Chinese paintings she grew up with in her own Chinese American household. But Wang had taken these elements further into abstraction.

“Red Cliff” by Victor Kai Wang, painted in 1989. “When you’re young, you don’t really know how to paint yet. You’re just hoping to paint well, paint realistically,” Wang says in a documentary his son made about him. “By the time you learn how to paint realistically, you realize it’s not enough.” (Victor Kai Wang)

Painted with marking-pen ink on paper traditionally used to print photos, the dark green of the forests blotted out like a Rorschach test. White waterfalls flowed with negative space and rocks appeared weathered into cragged strata. The shapes of semidiscernible natural elements looked swirled and wrung out, much like Francis Bacon’s tortured portraits. Wang’s unique technique lent the works an ethereal but immediate, highly contemporary quality.

“This one was my favorite, immediately,” Barnett says, during a recent visit to the Wing Luke. She gestures toward a large painting titled “Red Cliff” — one of those she selected from the stacks in Wang’s studio. On it, a vague, tigerlike face disappears into a swirling, merging mass of rocks and vegetation. Drips and discoloration bleed through the surface. “I can’t believe it’s from 1989,” Barnett says. “It looks like it was painted this year.”

The 1980s were a difficult period for Wang, who had studied art history and philosophy in Guangzhou, China, but had been forced into manual labor during the Cultural Revolution. After moving to the U.S., Wang painted signs for restaurants and washed dishes, raising his two sons largely alone while his wife, who is half American, struggled with PTSD caused by her internment in a “re-education” camp during the Cultural Revolution.

A job doing color correction at local photo studio Yuen Lui — regionally known for the school photo business — would deliver him his artistic breakthrough: Wang found huge amounts of scrap photo paper, on which he started to paint with marking-pen ink and a thick brush, which renders a watercolorlike, translucent effect. He figured out that a special solvent could dilute the ink, working as an eraser of sorts, which gave him the power to create negative space in a way that watercolors don’t usually allow.

“It was such a difficult time for him, with his wife going through that,” Barnett says. “So when he struck on this new technique, he was so excited.” It was this innovation that brought him joy, she says. “And it has helped him heal.”

The joy found in innovation echoes through in the work of the other artists in the show. Case in point: the flamboyant, feather-topped fabric installation by Suchitra Mattai. Displayed in an oblong, hallwaylike room, strings of braided vintage saris cascade from the ceiling and spill out onto the floor. “She’s always trying to tell that story of [her ancestors] crossing the Atlantic, having this difficult journey, being taken from their homes to basically be slaves,” Barnett says of Mattai. “But [she turns] the story into one that’s more joyful and reimagines it, giving them more power, especially the women.”

Curator Lele Barnett in the exhibit “Reorient: Journeys Through Art and Healing,” at the Wing Luke Museum on Wednesday, June 8, 2022. On the right, a painting by Jean Isamu Nagai, and in the background hang "Skins" made from T-shirts by Seattle artist Tuan Nguyen. (Amanda Snyder/ Crosscut)

Also reusing clothing is Seattle-based artist Tuan Nguyen, whose family fled the Vietnam War to the U.S. when he was a child. Eight tiger skins line the wall. Instead of fur, these are made from T-shirts Nguyen has deconstructed and ripped apart, blotting them with bleach and ink. “They’re about assimilation…. The kinds of skins that we wear,” Barnett explains.

Lining another wall are a series of sculptures made from wood panel, gesso, acrylic, driftwood and canvas. With dead branches sticking out and parts swaddled or patched together, the sculptures look like nests that might have been made by a velociraptor. They are imbued with a sense of suffering. Nguyen calls these his “pain bodies,” after an Eckhart Tolle concept, the residual and accumulated pain that lingers in your body and brain.

“What he’s trying to do in his work is healing cultural collective pain,” Barnett says. But, she adds: “He’s also taking apart the medium of painting, finding his way through that pain with experimentation.”

So is Jean Isamu Nagai, the Seattle-born artist who now works from L.A. and often incorporates unconventional materials in his paintings. In the three works on view at the Wing Luke, you can see the granules of pumice he has mixed in with his paints. The volcanic rock adds another layer, suggesting the rub of cultural assimilation that Nagai struggled with, the grit required to survive. The large, bright, semiabstract paintings (whose pointillism recalls traditional Indigenous Australian painting), shimmer with splendid sunset hues — orange and yellow and purple and pink. The warm, inviting colors are another artistic approach to healing, Barnett says.

Barnett started putting together the show in January 2019, and the exhibit’s message has become even more relevant since. “We needed healing before the pandemic, but we need healing more than ever right now,” she says. “And I’ve always believed that art has … the power to heal.” That belief applies not just to the viewer, but to the artists.

And, in a way, it has proved true for Barnett herself. Her chance encounter with Wang’s work has reminded her of the joy of discovery, too. “As an art adviser, I visit commercial galleries, travel to art fairs and follow auction records,” Barnett reflected in a recent email. “I get caught up in the art market and often forget what it’s like to have a spiritual experience with art.”

"Colored Mountains," a painting by Victor Kai Wang from 1994. (Victor Kai Wang)

“Victor has done nothing but that. He doesn’t sell his work; he doesn’t want attention or fame,” Barnett wrote (in fact, he told her, in 2019, “Don’t make me famous”). “He has been able to stay pure with his art and focus on creating and innovating as a spiritual journey.”

This is likely to change now, and Wang is somewhat reluctant to see it happen. But at 88 years old, he decided he should put his collection — and legacy — in his descendants’ hands. His sons, both successful in tech, want people to experience and enjoy his work.

“I’ve already had such an amazing response after posting some of the pieces on Instagram,” Barnett wrote. “An adviser friend messaged saying she has a client for these, and [asked to] please send pricing. It feels strange — and kind of wonderful, in a way — to promote an artist who can't be bought,” she said. (While the oeuvre is now in the hands of his sons, Wang told Barnett he’d prefer not to see the works sell in his lifetime.) “It’s giving me a moment to simply love art, to find and enjoy beauty, and that’s what Victor wanted.”

That’s evident when Wang shares his thoughts about the artist’s search — and the human longing — for beauty in a documentary about him (made by one of his sons). “Everyone loves beauty,” he says. “Not just beauty in terms of appearance,” he explains, “but also in how we live, how we care about society, how we look after one another — this is all beauty.”