Julia Ruuttila gripped the baseball bat. The women standing next to her at the gate of the Portland sawmill gripped rolling pins, scraps of lumber — whatever they could find to defend themselves from the attack they knew was coming.

It was the fall of 1937. Ruuttila and the women with her were members of the Women’s Auxiliary of the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), a timber workers union founded only a few months earlier. Determined to keep these leftists out of their sawmills and logging camps, employers in the Northwest timber industry had refused to bargain with the fledgling IWA. In response, the IWA went on strike for union recognition.

The strike that followed was one of the bloodiest in Northwest history. Mill security guards, strike breakers, and even members of rival unions attacked and beat IWA picketers. Trucks driven by IWA members were overturned. Riots on the picket lines quickly became so routine that the press stopped reporting them.

As the months passed, the violence became so bad that several IWA men were threatening to abandon the new union and cross the picket lines. And that’s what’d brought Ruuttila and the women’s auxiliary members to the mill gates that morning.

“We were not about to let our husbands go through the picket lines,” she later remembered.

Ruuttila and the auxiliary members did not work in the mills. Most, in fact, did not work outside the home. And since they didn’t technically work in the industry, they weren’t eligible for membership in the union, only its women’s auxiliary. Yet, as they saw it, the fight for unionization and better wages was their fight as well. Because they did not — or more usually could not — work outside the home, their material existence hinged on their husbands’ wages. The responsibility for feeding, clothing, and caring for the family fell to women. So when their husbands’ commitment to the union and the better life it offered began to falter, it was women who proved more willing to take up the strike and face down the “employer goons,” to use Ruuttila’s term.

But the violence Ruuttila and the auxiliary members were prepared for never came. In fact, because the strikebreakers refused to attack women, their presence allowed the pickets to go on, free from violence for the next eight months. Moreover, the picture of Ruuttila and the women’s auxiliary holding the picket line, ready to fight with rolling pins if need be, circulated widely throughout the IWA’s newspapers and the Northwest labor press, inspiring support for the IWA and helping the union to win the strike.

This would not be the last time Julia Ruuttila would throw herself in harm’s way in the name of activism. In the 1930s and 1940s, she was a part of the effort to expand the power of unions. In the 1950s, she fought for civil rights and against the country’s communist witch-hunt. In the 1960s, she protested the Vietnam War, and in the 1970s, against policies that disproportionally affected poor people.

What’s most remarkable about Ruuttila’s life is how her activism spanned so many causes and generations. Yet if there was a theme that linked Ruuttila’s battles, it was her belief that economic justice and women’s rights were tightly linked. It was women, she said, who shouldered the burdens of poverty, had to stretch paychecks and find ways to provide for a family on insufficient wages. It was therefore women who truly understood why it was necessary to fight against injustice.

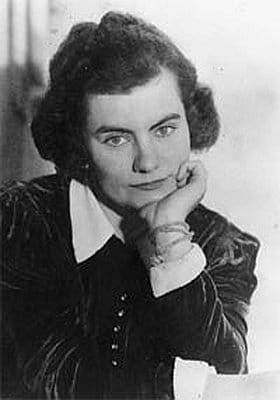

Julia Ruuttila was born Julia Evelyn Godman on April 26, 1907, in Eugene, Oregon. Her mother worked in the home. Her father was a logger, and like most Northwest loggers in the early twentieth century, he barely earned enough to keep food on the table.

While her parents may not have been able to provide Julia much in the way of economic stability, they did provide her with a radical education. Her father was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, a union known for its frequent strikes. Julia grew up singing songs from the union’s Little Red Songbook, which talked about a future free from want, in which workers controlled the means of production. Her mother was a suffrage activist and a birth control advocate. She taught Julia, from an early age, that women belonged at the forefront of fights for equality.

But it was Ruuttila’s experience as a working-class woman in the early years of the Great Depression that truly laid the foundation for her lifetime of activism.

Though only in her early 20s when the Depression started in 1929, Ruuttila had already lived a life of considerable hardship after she left her family’s home around the age of 17. She’d married a sawmill worker, though the relationship fell apart within months when unsteady work and the ensuing economic hardship made it difficult for the couple to stay together.

In the late-1920s, Ruuttila married Butch Bertram, also a sawmill worker. Her second marriage lasted longer, but was once again strained by poverty. The couple travelled widely as Butch looked for work. When Ruuttila became pregnant and the couple decided they could not afford to support the child, Ruuttila had a botched abortion, conducted by a doctor with questionable credentials. Ruuttila spent several months in the hospital afterwards.

In 1928, Butch finally found steady work at a sawmill just outside of Portland, in the small company town of Linnton. Even before the Depression, life was difficult for the town’s working-class residents. Wages at the mill were poor, and women like Ruuttila learned to sew to keep clothes serviceable, or took up gardening as a way to keep food on the table

“In company towns in those days,” Ruuttila remembered, “workers were no better than serfs.” The homes workers lived in offered little comfort. Ruuttila remembered that they were “duplexes … with knotholes so big you could look through into the next apartment and see your neighbors quarreling over which bills to pay.”

Then the Great Depression hit. Work became unsteady, the employer cut wages, and layoffs became routine. For the women in town already struggling to feed and provide for their families, it was too much to bear.

And so when the industrial union movement came to the Northwest timber industry, promising better wages and a higher standard of living, it was women, often more so than men, who were eager to join the uprisings of workers.

Ruutilla’s husband was initially ambivalent about joining the labor movement, but she wasn’t having it. “This is industrial war,” she told him. “It’s the real thing and we belong in it.”

Scenes like this were common across the entire Northwest timber industry. Women regularly pushed their husbands to join the union and fight for better wages, or went door-to-door with stacks of union cards, encouraging men to sign. One woman, Ruuttila remembered, threatened to leave her husband if he didn’t join the labor movement.

Women’s effort to build unions was not without irony. Women may have taken on the difficult work of organizing, but because they did not technically work in the industry, they were not eligible for union membership. Instead, they supported the movement through women’s auxiliaries.

Women’s auxiliaries had long been a part of the organized labor movement, though they mostly functioned as social spaces. Not so in the IWA. In the late 1930s, Ruuttila was elected president of the Portland IWA Women’s Auxiliary. She transformed it from a simple social organization to a truly activist organization. In addition to walking pickets and supporting strikes, auxiliary women became the political wing of Oregon’s IWA. They packed city council meetings in support of affordable housing ordinances, lobbied for health care reforms, and put pressure on employers to improve living conditions in company towns.

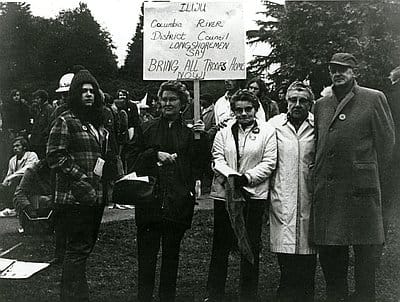

Women's Auxiliary march to Victoria in 1947.

During the Depression Ruuttila also discovered another weapon she would use throughout her life: the typewriter. In the late-1930s, she started writing for the IWA’s newspaper and the Northwest radical press, using her articles to encourage the all-male union to take an active stand on women’s issues. Her writing promoted the activities of the auxiliary, made the case for equal-pay for equal-work, and argued for legalized abortion and birth control.

Over the course of the next few decades, Ruuttila continued to work on behalf of the labor movement, and became a more vocal proponent of the Civil Rights Movement. She joined the NAACP in 1937, and when the IWA was ambivalent about extending membership to Japanese workers, she encouraged Japanese women to join the auxiliary.

But it was a flood that transformed Ruutila into a more vociferous civil rights activist. In 1948, the Columbia River unexpectedly flooded and wiped out the homes of the large African American community of Vanport, on the outskirts of Portland. The natural disaster left the overwhelming majority of Portland’s African-American population homeless. Ruuttila went to the Portland Housing Commission and demanded accommodations be made until Vanport could be rebuilt. When she was rebuffed, she began publishing a series of scathing articles that highlighted the Housing Commission’s indifference to the African American population.

Ruuttila also put pressure on the labor movement to open up membership to African Americans. In 1943, Ruuttila divorced again. She married briefly for a third time, before marrying her fourth and final husband, Oscar Ruuttila, a longshoreman and a member of the International Longshoremen’s and Wharehousemen’s Union (ILWU).

The ILWU was a proponent of civil rights nationally, but the Portland local was far more conservative. Writing in the longshoremen’s newspaper, Ruuttila condemned the Portland local’s exclusionary policies and became a member of the ILWU’s Women’s Auxiliary and worked to open auxiliary membership to women of color.

Ruuttila eventually reached out to women in the NAACP and Portland’s Urban League, and women in the groups started attending one another’s meetings. Within a year, they organized a protest that forced the Portland City council to pass a public accommodations ordinance.

Such victories emboldened Ruuttila, and encouraged her to expand her activism. In the late-1950s she was visible at protests of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which notoriously attempted to hunt out Communist infiltrators in the United States. In the 1960s she was heavily involved in the anti-Vietnam War Movement.

But perhaps it was her last big campaign that she’s best remembered for. In 1975, Pacific Power and Light (PP&L) raised electric rates. Ruuttila argued this would disproportionately affect the poor, and both she and a friend occupied PP&L’s offices, refusing to leave until they met with PP&L’s director. Their prompt arrest received extensive news coverage, and the widely circulating images of the police carrying off two seventy-year old women proved a potent symbol for their cause.

Shortly after what Ruuttila referred to as the “PP&L caper,” though, her health began to fade. In 1976 she was hospitalized with the flu and was forced to take up residence in a retirement community, which she did only grudgingly. Still, old age and failing health did not dull her activism. Throughout the 1980s, she could be seen wandering the halls of the retirement community, distributing pamphlets about nuclear non-proliferation or registering voters for the Democratic Party.

Not long before her death in 1991, oral historian Sandy Polihuk extensively interviewed Ruttila. for what would become her biography, named Sticking to the Union: An Oral History of the Life and Times of Julia Ruuttila.

While Ruutilla’s story is that of a remarkable woman, she was only one of the few committed women activists of the era. These women, most of whom are unsung, were the foot soldiers of the twentieth century’s major social movements. They walked the picket lines of the labor movement, they helped organize for civil rights, and their stories remind us that because women often bear the burdens of poverty and injustice disproportionately, they’re often more willing to take a stand.

Or, as Ruuttila put it: “Women are more radical than men. I really believe that.”

--

Steven Beda teaches history at the University of Oregon. His research explores the history of labor activism in the Pacific Northwest timber industry. He is currently writing a book about Northwest timber workers’ unions and environmental politics throughout the twentieth century. His dissertation won the Labor and Working Class History Association’s Gutman Prize for Outstanding Dissertation. He received his PhD from the University of Washington in 2014.