In the theater, a “technical rehearsal” is an all-day, all-hands-on-deck affair. With opening night imminent, stress levels are high. Under the director’s watch, every aspect of a show, down to the most minute detail, is closely examined for last-minute adjustments.

At Seattle Repertory Theatre on a recent afternoon, the play under scrutiny was the world-premiere staging of the holiday play Mr. Dickens and His Carol, a fantasia about the famed novelist and his enduring story “A Christmas Carol.”

As director Braden Abraham, playwright Samantha Silva and the show’s designers and other staffers watched from worktables in the Rep’s darkened Bagley Wright Theatre, the actors (outfitted by Catherine Meacham Hunt in top hats, full-skirted gowns and other Victorian garb) went through their paces line by line, step by step, gesture by gesture.

They were often interrupted by Abraham and others — for a lighting correction, a modified bit of stage choreography, replacing a chair with a stool for better sightlines, an altered line of dialogue.

Such is the painstaking artistic sausage-making most patrons of the theater never see. And after the long pandemic pause, the festive Mr. Dickens is an unusually large and expensive undertaking, with a cast of 14, an elaborate mobile set designed by Scott Bradley and many other moving parts.

It is also Braden Abraham’s swan song as artistic director. After 20 years at the Seattle Rep, he’ll leave his post in January for a new position at the Writers Theatre in Chicago.

Members of the cast of ‘Mr. Dickens and His Carol’ in a rehearsal led by Braden Abraham at Seattle Rep. (Sayed Alamy/SeattleRep)

At the tech rehearsal, Abraham was clearly in his element — interacting with performers and crew with quiet assurance, calm and good-humored but laser-focused on the production. He roamed the auditorium to observe what the audience would see from every seat, and sometimes jumped on stage to chat and joke with the actors.

Abraham’s down-to-earth demeanor, diligence and openness to collaboration are lauded by many of his longtime colleagues. (Good luck finding any negative comments from those who’ve worked with him — even off the record.) That includes Seattle actor/playwright R. Hamilton Wright, who has played roles at the Rep since the 1980s and is in the cast of Mr. Dickens.

“Braden loves the dynamics between actor and director,” says Wright. “He’s a genuinely nice person. And he is completely OK, ego-wise, with having good ideas come from people other than himself.”

That isn’t always the case in showbiz. And Abraham’s lack of interest in hogging the limelight has perhaps obscured some of his many achievements at the Rep.

A Western Washington native, he began his career there in 2000 as a young intern, later ascending to artistic associate, and in 2008 was promoted to associate artistic director under former artistic director Jerry Manning, who appreciated his talent and creative ambition.

While overseeing the company’s New Play Program, Abraham commissioned, workshopped and staged fresh scripts (i.e., Photograph 51, The K of D) while putting his own intimate spin on modern classics (including Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge and Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, co-starring Abraham’s now-wife Cheyenne Casebier). “I liked the balance, I like the new work to talk to the old work,” Abraham said.

But it was the noteworthy newer plays that brought the Rep renewed success and visibility. Back in 2007, Abraham staged the controversial My Name Is Rachel Corrie, about a local college student who died while protesting Israeli policies in the Gaza Strip. Later he was deeply involved in co-producing the debut here of one of the Rep’s greatest hits: Robert Schenkkan’s two-part drama about the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, All the Way (which went on to Broadway, won a Tony Award and was filmed for HBO), and its sequel The Great Society (which the Rep commissioned).

When the much-respected Manning passed away unexpectedly in 2014, Abraham was stunned. “When Jerry died it was terrible,” he recalled. “Hard personally and a big transition for the theatre, a real shock.” The Rep’s board skipped the customary national search for a new artistic director and named Abraham Manning’s replacement. “I was set up because of how included I had been in the leadership,” Abraham explained. “I was ready to expand the reach of the theater … I had a good sense of where we could grow.”

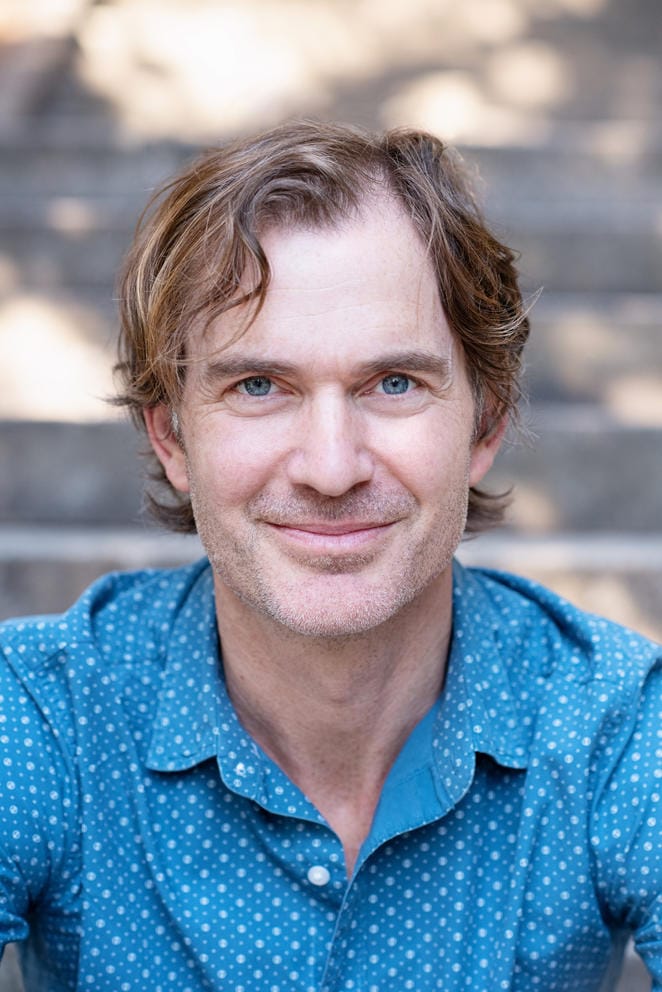

Braden Abraham has spent the past 20 years with Seattle Rep. (Bronwen Houck)

Seattle Rep managing director Benjamin Moore (one of Abraham’s chief mentors, along with Manning and another former Rep artistic director, David Esbjornson) knew how unusual it was to hand the reins to such a young artistic leader. Abraham was 37 and had never run a resident theater — much less a nationally lauded one with a $10 million-plus annual budget (it’s now $16 million) and a big staff.

“This transition was so complicated, so challenging, with Jerry’s unexpected passing,” said Moore. “And my planned departure after 28 years at the Rep was a simultaneous event. But Braden’s background, in terms of building strong relationships with local artists, and his long tenure in the company, were major factors in stabilizing the organization.”

In the decade since, Abraham and Jeff Herrmann (Moore’s successor as manager) have faced new challenges. The nonprofit Rep had amassed a large, growing deficit by 2015, which led the theater to dip into its endowment and end some popular education programs. (Recently it reduced the deficit by two-thirds, to a more manageable $1 million, at a time when 30 percent of U.S. nonprofit theaters are carrying debt.)

In addition, shows were not attracting enough younger patrons — another industry-wide problem — which Abraham and Herrmann attempted to address in part by bringing in the immersive, clubby David Byrne musical Here Lies Love. The costly venture (which required a total rebuild of the Bagley Wright space) did attract more millennials and the run was extended.

The Rep also staged popular works by young, upcoming and unconventional local theatre artists like playwright/musician Justin Huertas and drag performer Jinkx Monsoon.

And Abraham scouted and nurtured a winner in Come From Away, a folksy musical the Rep co-produced with the La Jolla Playhouse about the small Nova Scotia town that hosted travelers stranded after the 9/11 attacks. “I thought it would do well,” Abraham recalled, with a laugh. “But some people said, ‘You’re doing a musical about 9/11?’ They thought we were crazy.” It drew an intergenerational crowd and went on to Broadway success.

More recently, theaters across the U.S. have faced serious demands to hire more artists and staff of color. The Rep has had a strong history of multiracial casting and producing playwrights of color (including the entire canon of August Wilson), but Abraham and Herrmann, both white, knew greater efforts were needed.

One was to adapt a program of New York City’s Public Theatre to create the Public Works Project, a recurring summer musical featuring amateur performers drawn from diverse communities around Puget Sound. “It’s one of the first things I did as artistic director,” said Abraham, “and a big cornerstone for me. I wanted to tie the theater more strongly to the community and use this platform to reflect the breadth and depth of the talent here.”

Notably, the majority of commissions the Rep has doled out so far in its ambitious “20 x 30” program (funding 20 new scripts by the year 2030) have gone to authors of color. “It is one of the things I’m proudest of,” Abraham said.

Kathy Hsieh, the Seattle cultural-investments strategist for the Mayor’s Office of Arts & Culture, praises the Rep’s support for such local locally based, nationally noted dramatists as Cheryl West and Keiko Green.

“One of Braden’s remarkable strengths as a leader is his ability to [give opportunities to] incredible people, trust them enough to lean into their ideas and give them the resources to grow and flourish,” Hsieh commented. “He is really gracious that way. I think his experience of starting as an intern at the Rep made him want to offer support to others.”

The cast in a scene from ‘Mr. Dickens and His Carol,’ the last play Braden Abraham will produce as Seattle Rep’s artistic director. (Lindsay Thomas)

During the pandemic, the Rep, like all Seattle theaters, went dark for well over a year, limited to various Zoom events. “We got enough money from the government’s COVID funds and other sources to keep going,” Abraham said. “We used the downtime for some renovation of the theater that we’d planned on. But our actors and other artists really suffered because there were no shows.”

By the time the curtain went up again this season, Abraham had agreed to a four-year contract extension. But when the job at Writers Theatre suddenly came up, he shifted gears. After 20 years with the Rep, and directing more than 20 shows on its Bagley Wright and Leo K. stages, he was ready for a new challenge.

There was “never going to be a perfect time for me to leave this theater that I’ve grown up in,” Abraham said, but he was enticed by the idea of working at an intimate professional institution that concentrates mainly on fostering new plays. “As a theater artist you never want to get too comfortable, and this takes me to a new community with new collaborators,” he said. “Hopefully I’ll also bring Seattle people to do things with me in Chicago too.”

The Rep board of trustees plans a national search to replace Abraham. Board chair Nancy Ward knows he will be a hard act to follow. “Braden has vision,” she asserted. “He’s not just chasing trends. Season after season, play after play, I’m just bowled over by how he picks the work, the writing and artists he finds, and how he always provokes community conversations about what’s on stage.”

Abraham will have no say in who follows him at the Rep, but said he hopes his successor will take advantage of a wealth of local talent, be an accomplished director or other stage artist (rather than an administrator) and “leave the theater better than they found it.”

He has himself grown professionally in the job. Some new plays he championed early on were disappointments. (So was Bruce, the soggy recent musical based on Jaws.) But producing all hits and no misses is virtually impossible, and taking risks can lead to better discoveries later.

It is too soon to tell how Mr. Dickens and His Carol (based on Silva’s same-titled novel) will fare with audiences. Season subscriptions are still way down (roughly half of pre-pandemic levels), so the Rep’s newest challenge is wooing back enough patrons to keep the company solvent. Some have fallen out of the theatergoing habit, others are still leery about attending public events — which is why the Rep recently instituted “mask-required performances,” certain dates when all audience members must be masked.

But Abraham has had a blast commandeering his last production at the Rep alongside some of his favorite Seattle cohorts. “One of the joys of this theater is that everything is in one building,” he noted. “You can walk through the scene shop and the rehearsal rooms and the costume shop and feel the talent of the artists and artisans who work here. This is a showcase for all their talents.”

Abraham’s presence in those rooms will be missed. “Braden is tremendously beloved,” says board member Ward. “He’s been with us for two decades. We’re so lucky for it — and that he built an artistic organization that can withstand him leaving.”