In 1870, a wealthy American millionaire traveled around the world in 80 days — not counting a two-month stopover in France to hobnob with the revolutionaries of the Paris Commune. His name was George Francis Train, an eccentric and vastly wealthy entrepreneur who amassed a purported $30 million fortune (in mid-19th century dollars!) in shipping and rail. He was obsessed with transportation, from urban tram systems to clipper ships to the Union Pacific Railroad. He was the Elon Musk of the Gilded Age — and left his mark on the Pacific Northwest.

French author Jules Verne wrote a novel that is said to have been inspired by Train’s travels. Around the World in 80 Days (1873) became a classic, and its latest incarnation is as a new series on PBS’ Masterpiece Theater. It stars David Tennant as the story’s protagonist, wealthy English oddball Phileas Fogg, who bets he can journey around the world in record time. (Tennant is used to playing eccentric travelers; he was once the galaxy-hopping Dr Who.)

The success of Verne’s book stimulated late 19th century interest in global travel, speed and new transportation technologies — which suited Train’s interests in a brisk global trade system. If today’s megabillionaires have eyes on space travel, Train’s vision was solidly terrestrial, but no less ambitious for its time.

The book also inspired adventurers to try and best Train’s original 80-day record. Most famous was the 1889 jaunt of American journalist Nellie Bly. Sponsored by the New York World newspaper, Bly raced around the world (heading east) in a mere 72 days. She completed her trip in January of 1890, beating a simultaneous female competitor by nearly a week.

Then, up stepped the budding, ambitious city of Tacoma. The Tacoma Ledger newspaper proposed to send the “real” Phileas Fogg, George Francis Train, on a second round-the-world trip, during which he would try to beat Nellie Bly’s record by taking a western route across the Pacific.

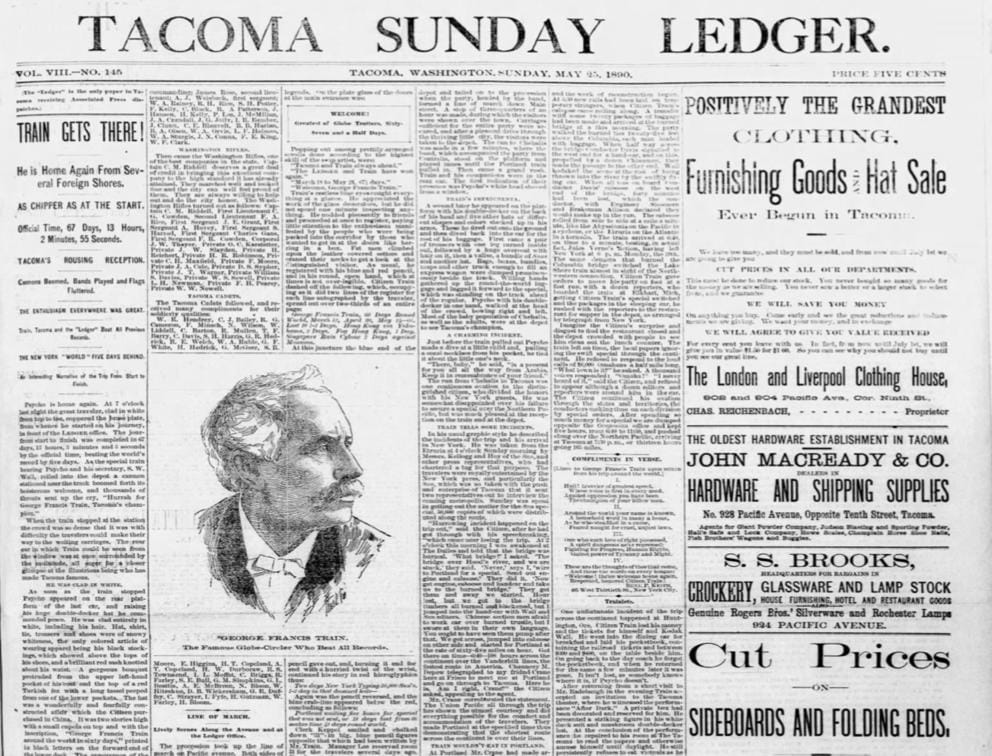

George “Psycho” Train (center, white hair) surrounded by children of Tacoma in celebration of his journey. (Washington State Historical Society)

Tacoma was desperate to regain its edge among Puget Sound ports by demonstrating that it was the best jumping off place for Japan and the Far East. The publicity, the paper calculated, would be enormous. Global trade could not ignore Tacoma’s advantages, including being hundreds of miles closer than San Francisco to Yokohama. The “City of Destiny” would be recognized as the gateway to Asia.

At this point in Train’s career, he was a self-described “crank,” an eccentric public figure known for his business success and weird ideas. He had run as an independent for president in 1872, but no one rallied to his cause. He had supported not only the Paris communists, but Irish rebels — neither considered “sane” behavior for a 19th century megacapitalist.

Train was a believer in “psychism,” wherein he thought he tapped into universal energies that made him smarter and wiser than any other human being on Earth. All great men, he asserted, had access to this energy stream, which could ignite worldwide transformation. He believed he would live to be 200 years old. He referred to himself as “Citizen Train,” for his support of the masses, but he also adopted the title of “The Psycho.”

Writings poured out of him, often barely coherent. He published his own newspaper and made oracular pronouncements while sitting on a park bench in New York City. (If only he’d had access to Twitter.) Between his oddball beliefs and business success, he was constantly in the news.

But he embraced Tacoma with zeal, becoming a huge city booster. It was Train who coined the anti-Seattle phrase, “Seattle, Seattle, death rattle, death rattle,” to indicate how the town on Commencement Bay would rule the region, if not the world.

In May, 1890, the Tacoma Ledger ran a front page story about Train’s journey and return.

When Train arrived in Tacoma in mid-March of 1890 to begin his journey, the Ledger’s headline read: “Tacoma Went Wild.” There were parades, banquets, booming cannons, and Train gave interviews and lectures. Mobs crowded The Psycho’s carriage just to catch a glimpse of the great man who would make their city greater still.

Train’s was not a journey in strange contraptions — hot air balloons or elephants. Instead, it showcased the already established network of rail and steamships that could reliably speed a determined traveler around the globe, especially if one had means. It certainly sparked public interest in the globalization of trade and travel.

The stunt gained international publicity, so much so that other Puget Sound rivals tried to hop onto its coattails. In Seattle, people suggested that Train take Princess Angeline, Chief Seattle’s aged daughter, along on the trip from Tacoma to Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, Suez, the Middle East, Europe and back. In Port Townsend, a young local woman, Regina Rothschild, was alleged to be planning a similar trip heading eastward. Neither happened, but the speculation generated some publicity.

Train had the skills of a social media influencer — reflected by the fact that The Ledger had printed bundles of miniature newspapers he was to distribute on his trip. And though he could speak in avalanches of prose, a private secretary, Samuel W. Hall, accompanied him in order to send occasional dispatches that told the world more coherently how the journey was progressing. Hall also recorded the trip with a camera, which got him dubbed as Train’s “Kodak amanuensis.”

International business connections earned Train a string of friends and contacts at nearly every major stop, but they also challenged his ability to stay on time. Along his journey, he berated rickshaw drivers and Arab laborers, but at the same time, showered attention on foreign babies and children. He regaled fellow travelers with stories of his past adventures and enterprises, and he exhibited unusual Victorian sympathy for some of the less fortunate. On the Cunard liner Etruria on the Atlantic leg to New York, he attempted to organize the steerage passengers to rebel against mandatory vaccination requirements. The Psycho’s work was never done.

Train finally arrived back in Tacoma on May 24, 1890. A chamber of commerce historical marker clocks his journey at 67 days and 13 hours, beating Nellie Bly’s record of 72 days.

How did the stunt work out for Tacoma? There was some complaining that the press coverage was more about Train than the City of Destiny. Still, The Ledger tallied the successes in terms of raw publicity: At nominal cost ($6,000), the paper concluded the city had received at least a billion media mentions and had exposed Tacoma to at least 80,000,000 newspaper readers in the U.S. and Canada. If there is anyone who hasn’t heard of Tacoma, The Ledger wrote, “it is his own fault.”

The only city newspapers that didn’t cover the event extensively, the writers observed, were those in rival Northwest cities like Seattle and Portland. But folks did pay attention in Whatcom, now Bellingham. In 1892, that growing city sponsored a third circumnavigation by Psycho Train — during which he finally cut his travel time down to 60 days.

It stood as a measure of progress and technology that carried into the era of (well-funded) flight. Train had gone around the world in 60 days. In 1929, a German zeppelin made the journey in 21 days. In 1995, the supersonic Concorde jet did it in less than 32 hours. And now, Musk’s SpaceX capsule can orbit passengers around the globe in a leisurely 90 minutes.

Despite his place on this roster of achievement, Train died poor in 1904. He had given much of his fortune away and lived in a cheap hotel in New York. Newspapers like The Ledger lionized him and defended his eccentricity. Train himself said his around-the-world journeys were typical of life lived at a frenetic pace.

“I have lived fast,” he wrote in a 1902 autobiography. “I have ever been an advocate of speed. I was born into a slow world, and I wished to oil the wheels and gear, so that the machine would spin faster and, withal, to better purposes…. I wished to add a stimulus, a spur, a goad — if necessary — that the slow old world might go more swiftly, and ‘fetch the age of gold,’ with more leisure, more culture, more happiness.”

While local civic boosters may have derived some publicity for their ambitious communities, Tacoma and Whatcom were not endpoints but jumping off places for the better, faster world Psycho Train envisioned. Whether more happiness ensued is another question.