When Skagit Valley artist Todd Horton learned that trees communicate with each other, he was determined to depict the phenomenon on canvas.

He’d just read The Overstory, by Richard Powers, a novel based on the scientific evidence that trees “talk to” each other through root systems, fungi and airborne chemical signals (aka the “world wood web”).

“I loved that book,” Horton recalls. “So I was like, well, how can I translate that idea into my art?”

Known for his paintings of regional landscapes and animals — misty views of the Samish River, blue-black crows in conversation — Horton first tried to convey his imagined dendrological chats by drawing trees with root systems visibly connected underground. The results were intriguing to him, but didn’t feel sufficient.

This was about four years ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, when people were trying all manner of new endeavors. Horton had a wild idea of his own. “I kept thinking about it and pushing it,” he says, “which eventually led to the trees themselves making the marks and telling a story.”

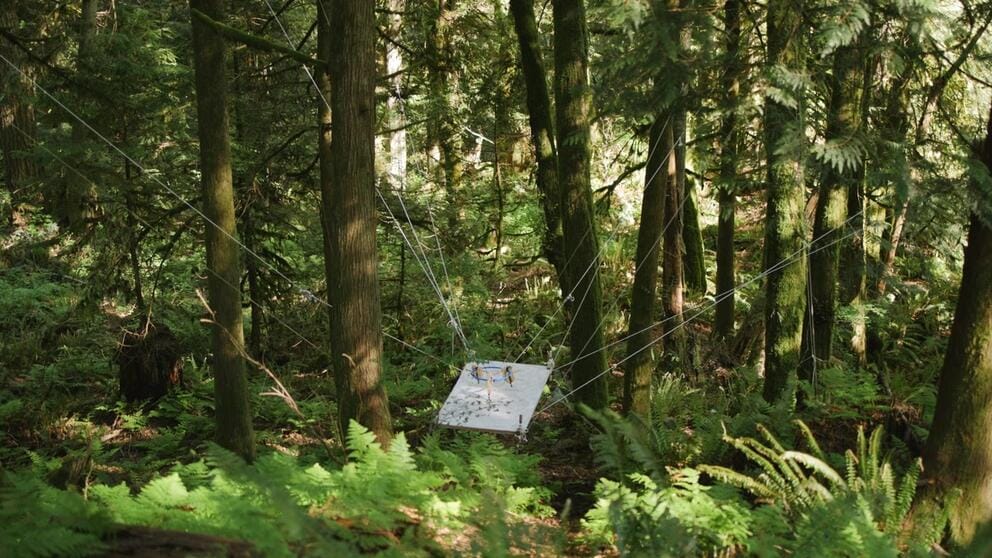

Driven by the poetic idea of visually transcribing the dreams of trees, Horton constructed “drawing devices” from simple materials: clotheslines, carabiners and wooden clamps that grip black chunks of graphite or white lumber crayons.

One of Todd Horton’s tree drawing devices suspended in a forest off Chuckanut Drive. (Still from ‘Art by Northwest’)

He set out into the forests of Bow and Edison and strung the devices up in the trees above blank canvases. The trees’ movements made captivating markings — with an assist by wind, rain, snow and the drying effects of sun.

“It was exciting,” Horton recalls of these early forays. “Each day I would hike up into the forests and see what happened. It was always unexpected and fun.” He especially liked getting out of the studio and “dealing with the environment directly.”

Horton decided to keep pushing it, experimenting with old truck tarps, hollow-core doors and vintage sheets of paper as his canvases. He named his series the Topographia Index, from the Greek meaning writing about place. But in this case the place itself is doing the writing.

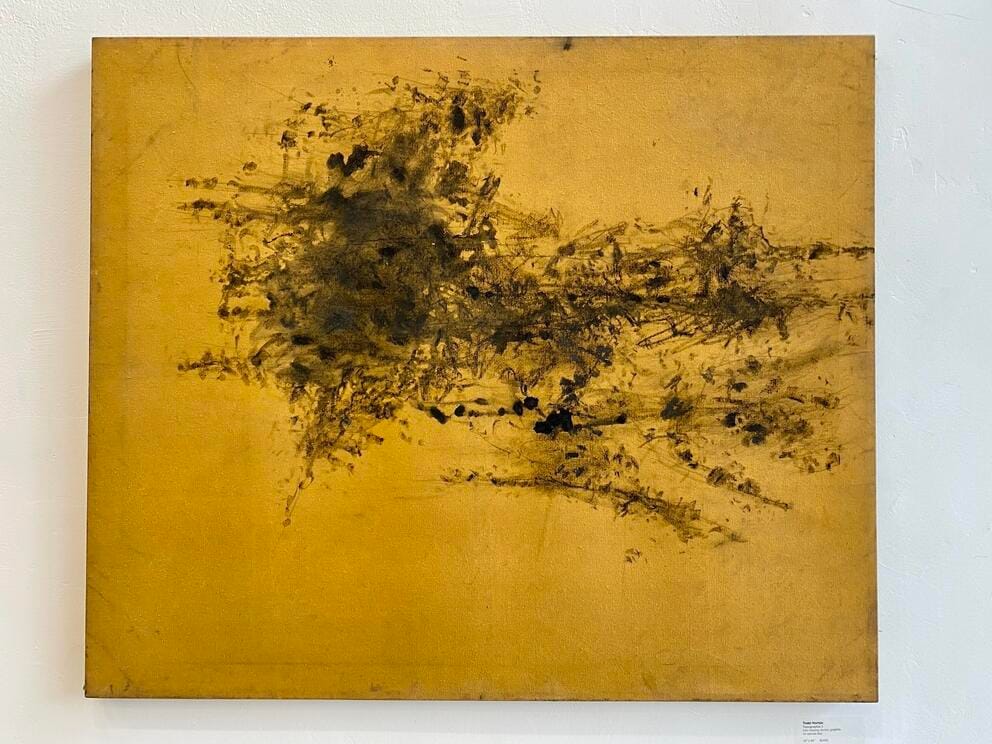

Dark clusters of dots and dashes, waves of grassy lines, pockmarks that seem to have been jabbed into the canvas — the resultant markings look intentional, resembling abstract expressionist paintings. If you saw the finished pieces without knowing his process, you might assume Horton was the one doing the drawing.

This piece from Todd Horton’s ‘Topographia Index’ is a collaboration featuring black graphite markings made by tree movement and a white wash applied by the artist. (Brangien Davis/Cascade PBS)

Some of the works could be considered a human/tree collaboration — such as when Horton removes the canvas and adds his own gesso wash before returning it to the woods. He repeats this process, for a month or a year, until he sees something “visually interesting.”

In a recent solo show at Perry and Carlson Gallery in Mount Vernon, Horton’s assembled works shone with starry mystery. Some had dark circles of graphite that looked like black holes. Swirls of white crayon resembled nebulas. Others seemed to depict murmurations or constellations. Horton finds these celestial similarities intriguing.

“There are old stories and myths from around the world where the trees connect the earth to the sky … these pillars that uphold the whole cosmos,” he says. “I like that reference … suggesting stars in the night sky … a mysterious map of the sky the trees are transcribing for us.”

Horton’s studio is a bright-blue shipping container sited on acreage that backs up to the Samish River, with Lummi Island looming purple in the distance. A prominent eagle’s nest is perched in a small grove of trees on the premises, a favorite spot for birdwatchers to pull over and point their binoculars upward.

Inside the studio, Horton is surrounded by artistic projects past and present, including wooden block prints in homage to Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman — fellow artists who based their work in the study and translation of nature.

Todd Horton’s shipping-container studio looks out at wide green Skagit Valley fields. (Brangien Davis/Cascade PBS)

A couple Topographia Index projects hang in the trees just outside. Remnants of the resident eagle’s lunch often end up on the canvas — feathers, bones and duck feet — not to mention tree resin, seeds and bird poop, all of which add to the texture of the works and the sense that these pieces track the passage of time.

Surrounded by waterways, Horton wanted to hear what the river had to say too. “I got this idea about trying to record the emotional response of the river to the world around it,” he recalls. So he created a new invention — a “tidal drawing device,” made from charred wood, old cedar floats and plumbing tubing — and set it up at a bend in the Samish River.

In this case the canvas is wrapped around a piling, with the burnt sticks of wood encircling it. As the tide rises and falls, the charcoal makes marks that look something akin to calligraphy. Silt, sediment and pollutants add to the story.

Horton says interpreting the markings produced by trees and rivers is a bit like “reading tea leaves” (maybe reading tree leaves). But in his mind, he sees signs of stress in the scribblings. Local cedars have been dying inexplicably in recent years, he notes, and the river is suffering not just from recent climate change. “There’s a long history of humans manipulating and regulating this river,” he says, pointing to its legacy of dredging and dikes.

By inventing and implementing drawing devices, then tracking and interpreting the results as the stuff of tree dreams, Horton is blending scientific inquiry with poetic license.

One of Todd Horton’s “tidal drawing devices,” in which he wraps a river piling with canvas and attaches a circle of burned wood to make markings as the tide goes in and out.

His work feels strongly connected to that of The Northwest School — the loose group of local artists who made environmentally influenced work in the 1940s and ’50s. Mostly painters (including Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves and Guy Anderson), they reflected the regional landscape with earthy tones, symbology, misty washes and hints of calligraphy.

Sometimes called the Northwest Mystics, these artists often imbued their work with an element of mystery, a metaphysical sense of oneness with surrounding nature. Horton even has a close association with one such mystic: Clayton James, a longtime Skagit Valley painter with whom Horton shared a studio just before James died in 2016. Horton now uses one of James’ old wooden clamps in some of his drawing devices.

In many ways, Horton is a direct artistic descendant of these forebears — capturing the immediate environment on canvas and adding a hint of mystery. Having moved to the area from Ohio 20 years ago, he says his creative efforts have seen a definite shift after being in this place.

“Living close to the seasons and the changes … it’s just a different way of thinking,” Horton says. “I know it’s definitely changed how I make art.”

Watch and read more stories in Art by Northwest, a Cascade PBS series about how place affects art making.

Another piece from Todd Horton’s ‘Topographia Index,’ with graphite tree markings on a faded truck tarp. (Brangien Davis/Cascade PBS)