In the lobby of the Bellevue Arts Museum, a shingle-roofed farm building seems to have dropped out of the sky. But the jarring appearance is appropriate for a story of shocking displacement. Created by Seattle artist Michelle Kumata, Emerging Radiance: Honoring the Nikkei Farmers of Bellevue (through March 13) is a multimedia immersion that showcases the stories of Bellevue farmers who were unjustly incarcerated in Japanese American internment camps during World War II.

The striking piece came about after Kumata was commissioned to paint a similar large-scale mural for the Bellevue offices of Meta. The idea was to educate employees about the history of the location — specifically, the Japanese and Japanese Americans who operated local strawberry and sugar pea farms long before high-rise office buildings took over the landscape.

The mural was a success except on one front: the public could not access it. So the Meta Open Arts team helped Kumata create the freestanding, four-sided, augmented-reality-enabled “farmhouse mural” now on view at BAM.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

“Sixty farm families were removed from here,” Kumata said during the press tour. “Only 12 families returned.” Many of those who attempted to come back to Bellevue discovered that their homes had been burned or vandalized, their wells poisoned. Kumata did research with local nonprofit Densho, which 20 years ago had collected oral histories of displaced local farmers. In a clever use of tech, those voices are incorporated into her artwork.

The farmhouse is painted with striking graphic illustrations on all sides: farmers in 1940s dress; sprigs of snap peas and strawberries; and white-winged cranes (a symbol of hope) that direct your gaze around the tall cube. The faces of the farmers are painted a warm golden hue — a color of honor, Kumata said, but also a reference to racist slurs lobbed at Japanese Americans. “I think of yellow as a symbol of empowerment,” she added.

Artist Michelle Kumata working on the panels that were assembled into a cube to create the "farmhouse" structure at BAM. (ARTXIV)

As standalone murals, these are eye-grabbing enough, but they achieve three-dimensional depth when you click on the QR codes embedded in each image.

Most of the augmented reality applications I have seen over the past several years are little more than visual gimmicks. But this one — created by filmmaker and creative director Tani Ikeda — convinced me of the technology’s potential.

After opening the feature in Instagram, point your phone at the mural. The painted faces will suddenly become animated, as farmers Tosh Ito, Rae Matsuoka Takekawa and Mitsuko Hashiguchi tell their stories in one-minute clips taken from the oral histories. At the same time, animated plants unfurl, swoops of color swish by and cranes take flight. And in yet another visual layer, historic photos of local farms from the era emerge, superimposed on the mural. It’s both effective and affecting.

The roof of the farmhouse is asymmetrical, which Kumata said she intended to convey “something off or not quite settled,” because there is still so much unresolved about this history, so much lingering anti-Asian sentiment.

“Why don’t later generations know these stories?”

She asked the question, then shared a personal insight: Both of her parents were born in the Minidoka Relocation Camp in Idaho. “My parents were too young to remember, my grandparents didn’t talk about it, and I didn’t know enough to ask,” Kumata said. After being punished because they were seen as “different,” many Japanese American families emphasized blending in over stirring up bad memories.

As we mark the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 this month, Kumata hopes to facilitate more story sharing. On Feb. 19 at noon, BAM will host a virtual Day of Remembrance event, a conversation with Kumata, Tani Ikeda, Densho founding director Tom Ikeda and descendants of the Bellevue farmers featured in the artwork. They’ll talk about the history and legacy of Japanese incarceration, as well as the creation of the farmhouse mural, which Kumata says is “a container for these stories of strength and resilience.”

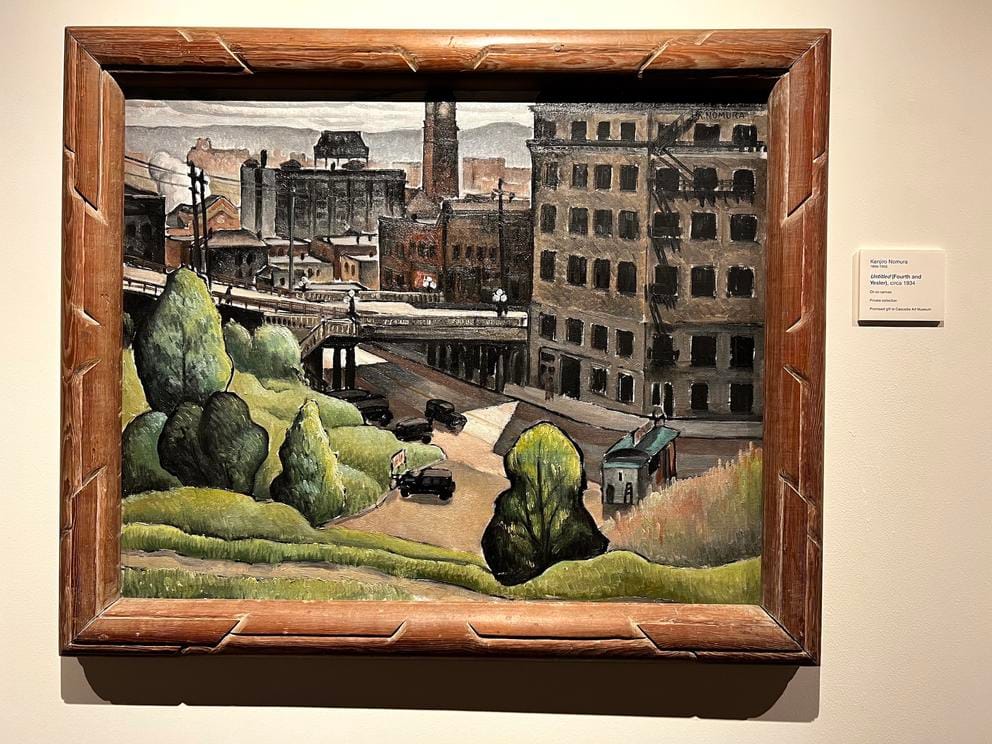

Kenjiro Nomura's painting of Yesler Avenue and Fourth Avenue in Seattle, circa 1934, exhibited at Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds. (Daniel Spils)

Another of these stories of resilience is currently on beautiful display at Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds. Worth the drive for even die-hard Seattle dwellers, Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey (through Feb. 20) explores the creative life of an artist who was one of the Northwest’s most prominent in the 1920s and ’30s.

Born in Japan in 1896, Kenjiro Nomura came to the U.S. with his family at age 10. He grew up in Tacoma, and by age 20 was living on his own in Seattle’s Japantown, trying to make it as an artist. He worked as a sign painter and took classes with Fokko Tadama, a respected Dutch-Indonesian painter who taught many issei (first generation Japanese American) artists in his Capitol Hill studio.

The Cascadia exhibit features several of Nomura’s earliest works, including portraits from the 1910s, as well as a fascinating collection of his modernist urban cityscapes from the 1920s and ’30s: old Ford cars lined up on Yesler Way, the Fourth Avenue train tunnel, the Smith Tower, houseboats on Lake Washington. His work was highly acclaimed and won awards. And when the Seattle Art Museum opened in 1933, he was the first regional artist to be featured in a solo show.

Kenjiro Nomura’s painting style changed drastically after he returned to Seattle from the Minidoka camp, as seen in ‘Puget Sound,’ from 1947, exhibited at Cascadia Art Museum. (Daniel Spils)

His career was skyrocketing as he worked among a group of artistic peers that included Kamekichi Tokita and Takuichi Fujii. Then: World War II.

Nomura, his wife, Fumiko, and son, George, were sent to the Puyallup Assembly Center before being transferred to the Minidoka camp. In both places, he painted extensively — scenes at the camps that are devastating in their plainspokenness: the water tower, the laundry, the outhouse. He used watercolors in soft blues and greens, but always there are dark clouds overhead, barbed wire in the distance.

Nomura and his family returned to Seattle in 1945. One year later, his wife took her own life. With the support of other midcentury Seattle artists, including George Tsutakawa and Paul Horiuchi, he started painting again, but in a totally different style. Seeing the contrast between these wildly abstract paintings and the ones he made before the war is jolting — and yet, it makes complete sense. His whole world was shaken up and turned on its head.

Cascadia Museum is hosting Conversations About Nomura this weekend (Feb. 13, 10 a.m.), featuring Densho’s Tom Ikeda with art historian Barbara Johns, who wrote the wonderful book that accompanies the exhibition. On Feb. 20, the museum will host a daylong Day of Remembrance (10 a.m.-5 p.m.), commemorating the signing of Executive Order 9066 with Taiko drumming, a Japanese tea ceremony, ikebana flower arranging, a calligraphy workshop and haiku writing — art forms that survived and flourished in the face of tremendous adversity.