Deciduous trees are currently engaged in their final flourishes — leafy bursts of copper, tangerine and crimson that hang above our heads like fireworks. In the new show at Seattle Art Museum, the fall colors come in primary hues, suspended midair in the marvelous mobiles and stabiles of artist Alexander Calder (1898-1976).

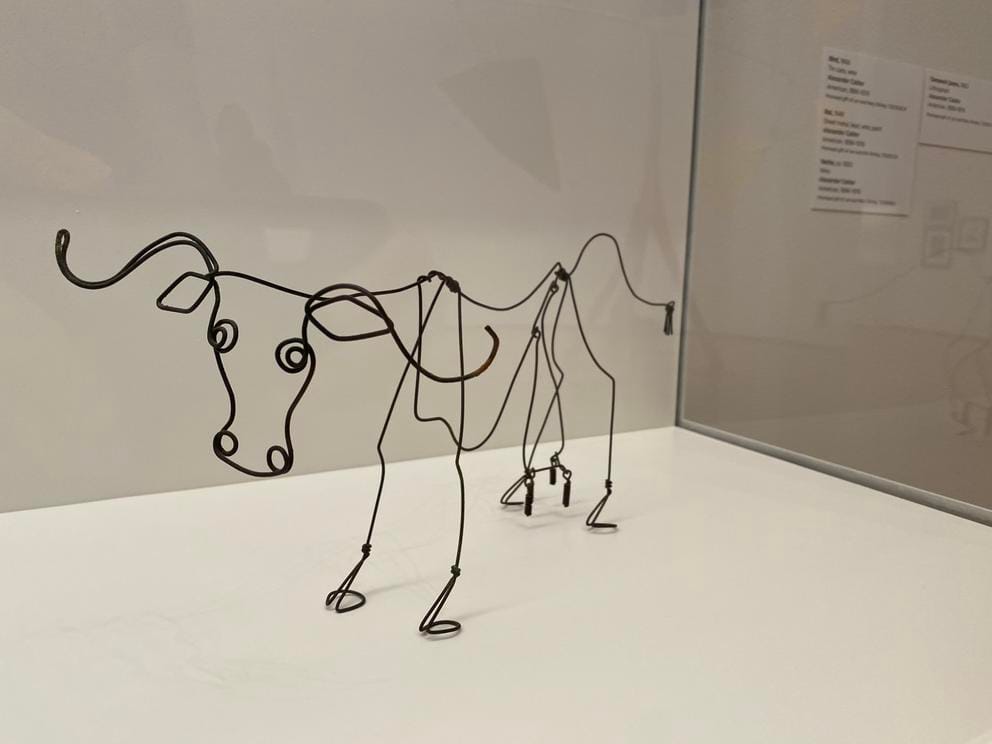

Calder: In Motion, The Shirley Family Collection (through Aug. 4, 2024) features 48 of the revolutionary American sculptor’s works. From delightfully delicate wire figures like “Vache” (c. 1930) to the comically imposing metal “Red Curly Tail” (1970) and including drawings and paintings as well — all the pieces were gifted to the museum by Seattleites Jon and Kim Shirley.

“Everything looks better here than in our house,” Jon Shirley, a former Microsoft executive, noted with a laugh at the press preview. I’ve never been to the Shirleys’ house but the exhibit looks terrific, set off by a tall, S-curved wall built to “hug” the largest sculpture.

Calder invented the mobile — so named by his friend Marcel Duchamp — and the double-height gallery allows plenty of space for the soft movement of the cascading leaves and branches of his signature pieces, which drift gently in the breeze of the HVAC system.

Trained as a mechanical engineer, Calder was entranced by spatial relationships, balance and counterbalance. His experiments in color and physics are doubly apparent in the intriguing shadows cast against the stark white walls.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

Calder was interested in astronomy, too — evidenced directly in his paintings “Moon and Waves,” “The Yellow Disc” and in his “Constellations” series. His sculptures often echo 3D models of solar systems in some faraway galaxy, places where levity holds as much sway as gravity. In this way, he created his own worlds.

“Moons and Waves” (1963), one of several of Calder’s paintings at SAM, reflects his abiding interest in space and astronomy. (Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society, New York. Photo: Nicholas Shirley)

I was surprised to learn that Calder lived for a time in the Northwest. Born in Pennsylvania, he spent parts of his career in the artistic hotbeds of New York and Paris. But in 1922, he worked as a timekeeper in a logging camp in Independence, Washington.

That connection came via his older sister and her husband, who lived in Aberdeen at the time. Another local connection: Calder’s wife, Louisa James, who was born in Seattle in 1905.

While at the logging camp, Calder was so inspired by the natural landscape he wrote to his mother and asked her to send paints and brushes.

Can we find hints of the regional influence in his sculpture “Femme Assise” (1929), an ebonized carving of a woman posing on a slab of wood? What about “Mountains” (1976), a large-scale, abstracted range? Both are on view (in the latter case, it’s the sheet-metal model for the final piece); both are black with stout and somewhat foreboding lines.

Calder wasn’t a fan of imposing “meaning” on his works, preferring instead that they be experienced in the moment — enjoyed for their wit, physicality and wonder. You’ll have plenty of chances to do so, as this show is the first in a Shirley-funded plan for annual exhibits, programming and collaborations, including with artists influenced by Calder.

In the meantime, for those captivated by the simple yet resonant lines in Calder’s early wire works … check out Seattle artist Shelli Markee, whose wire figures share a similar minimalist pleasure.

And mobile fans: Keep your eyes open (and upward) for the renegade “Time Traveling Dragons” by anonymous artist(s) SEA Dragonsss, whose cleverly balanced hanging creations keep mysteriously popping up around town (and now in Portland, Oakland and LA, too; see map).

Calder was one of the first artists ever to “draw” with wire. Several of his animal likenesses are on view at SAM, including “Vache” (c. 1930). (Brangien Davis/Crosscut)

While Calder’s individual works were always unique, he was constantly tinkering with several key elements: space, movement, balance and color. Combined, they make for wonderful artworks; separated, they make for a fine organizing strategy for other arts happenings on the horizon.

Movement and Balance

Calder was an aficionado and practitioner of performance and dance (and a lifelong friend of Martha Graham’s). One of the large mobiles displayed at SAM was used in the stage set for Joseph Lazzini’s 1969 ballet Métaboles.

You too can engage with dance this weekend via Love and Loss at Pacific Northwest Ballet (through Nov. 12). This tender triple bill features the titular piece by Seattle choreographer Donald Byrd; “Wartime Elegy,” Ukrainian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s tribute to his home country; and the world premiere of “The Window,” by Dani Rowe, artistic director of Oregon Ballet Theatre.

Color Theory

Calder stuck largely to primary colors (including his signature “Calder red,” as exemplified in “Eagle” at the Olympic Sculpture Park) because of their inherent counterbalance and impact.

You can experience a different take on color theory in The Water Series, a new show of paintings by California artist Hiroshi Sato at Harris Harvey Gallery (through Dec. 2). With a sense of isolation reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s work, these solitary figures in pastel and colored pencil reveal the power of hues to suggest emotions.

Theatrical Space

For an illustration gig in 1925, Calder sketched the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus over two weeks of performances. The action under the tent became a lifelong interest, and was the source of his early work Cirque Calder — for which he created and performed an entire low-fi mechanical menagerie (get a glimpse of it here).

At SAM, you can see seven prints from the “Calder’s Circus” portfolio, charming, minimalist lithographs that resemble his wire works.

If you share Calder’s appreciation for the shape a circus takes, head to Teatro ZinZanni’s new show (through March 31, 2024). Featuring trapeze artists, contortionists, aerialists and more feats of derring-do, the performance takes place in the high-ceilinged former church known as The Sanctuary (now part of the Lotte Hotel).

It’s one more way to watch things — leaves, kinetic sculptures, acrobats — fly through the air with the greatest of ease.