Seattle artist Barbara Earl Thomas reveals the subjects of her portraits with a clever technique: absence. Using stiff black paper, she cuts away strips and segments until the material reflects specific friends and colleagues — their facial expressions, hairstyles, clothing and body language. Each person gains presence and personality through a process of tiny cuts.

It’s one of several affecting metaphors in the new exhibit Packaged Black, at the Henry Art Gallery through May 1, 2022. Thomas’ work is paired with that of New York artist Derrick Adams — and it’s a perfect match. Both are concerned with Black identity, community and cultural resilience, specifically as expressed through fashion and adornment (both real and imaginary). And both use multiple layers, geometric patterns and lavish colors to create stunning pieces that demand a closer look.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

The result is an eye-popping walk through the galleries — I made several loops to soak in the details. Thomas’ portraits come alive via the multihued soft papers she places behind the black cutouts, recalling stained glass iconography in a cathedral. (More of Thomas’ exquisite cut-paper portraits are on view in The Geography of Innocence at the Seattle Art Museum through Jan. 2, 2022.)

Adams contributes several of his large-scale “Beauty World” images, in which he starts with photographs of wig salons and adds geometrically abstracted faces and vivid hair color with paint. Peer closely into each mannequin’s eyes and you’ll see a cloudy remnant of the process, which adds an animated aspect to the faces — as if they are lost in a daydream.

One of several large paper-cut gowns by Barbara Earl Thomas in ‘Packaged Black.’ (Brangien Davis/Crosscut)

Thomas also created several oversized ballroom dresses made entirely from intricately cut paper, one of which dominates the main gallery. It’s reflective of her interest in how fairy tales and other archetypal stories play into self-image — a Cinderella dream, she writes, “the every-person’s story I’ve fashioned Black.”

The flavor and ferocity of this must-see show is captured in this stanza from a poem by Thomas, included on the wall of the exhibit:

Dress up, dress down, dress to kill, dress to chill,

dress for success, dress to challenge

— it’s a vision

a meditation on the real and ideal,

our one chance to magnify or suppress

the perceived imperfection of our bodies.

Longtime Seattle artist Phillip Levine passed away in September. A retrospective of his paintings, drawings and sculptures is on view at Koplin Del Rio gallery. (Ben Lindbloom)

If you exit the Henry Art Gallery and turn right, you’ll cross the pedestrian bridge that spans 15th Avenue Northeast and encounter an iconic piece by Northwest sculptor Phillip Levine. The abstract bronze “Dancer with Flat Hat” (1971) is forever in motion — her knee bent under a twirling skirt, her arm crossing her body and pointing you down the stairs. It’s one of 30-some public works Levine has contributed to the Western Washington artscape and reflects his particular savvy in capturing the human figure.

Levine’s bodies aren’t always realistic. There’s often a stretched quality to them, with extra-long limbs, tiny heads and only the suggestion of facial features. The torsos are boxy — or sometimes absent entirely, revealing the vertical armature of the sculpture. But in their implied movements and gestures (they are always moving), the figures emanate an essential humanity.

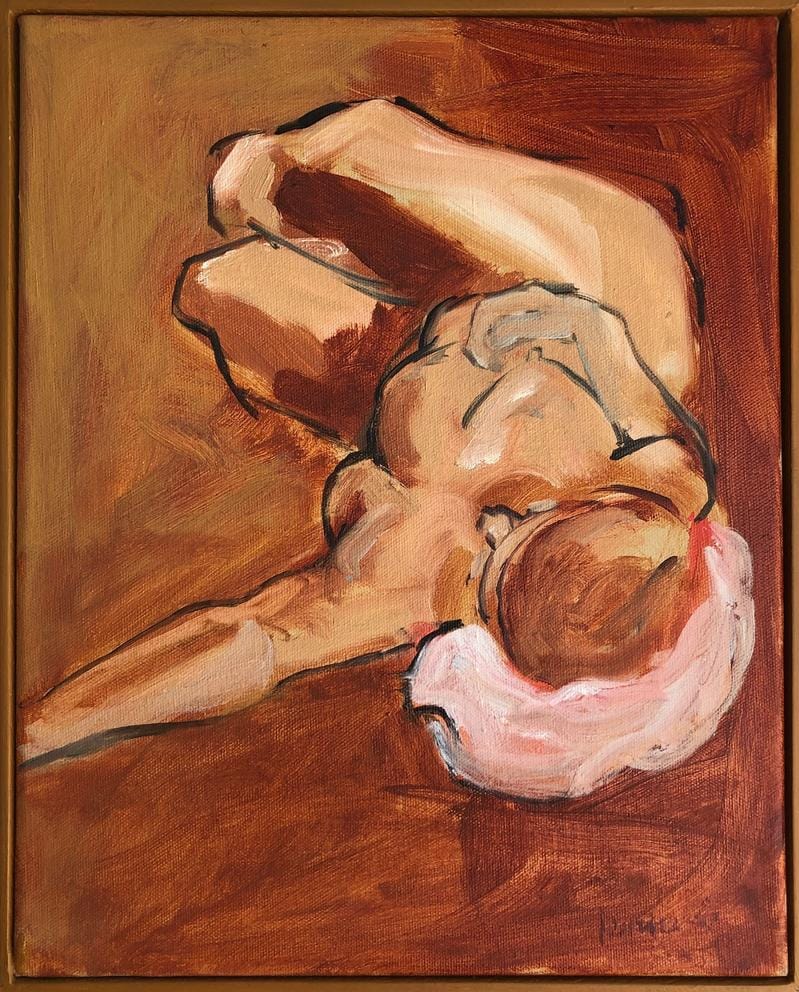

“White Pillow,” by Phillip Levine. (Koplin Del Rio Gallery)

After 70 years of making sculptures, paintings and drawings, Levine died on Sept. 19 at age 90. A retrospective of his work was already on view at Koplin Del Rio in Georgetown; gallery founder Eleana Del Rio told me he remained mentally sharp until his last day. Displaying a range of his works in bronze and on paper — in which human figures are dancing, leaning, stretching, scrambling and lounging around naked — Myth, Memory & Image (through Oct. 23) feels like an appropriately festive celebration of life.

“The world is full of boring nudes quite capably drawn,” writes Seattle artist Norman Lundin, in a recent tribute to Levine (his friend since 1968). He goes on to explain that what’s different about Levine’s nude paintings and drawings is their “inherent expressive quality … that quality that is the most elusive and most valued of all creative attributes…. It is the expressive quality in the work,” Lundin says, “that makes you believe what you are seeing is important.”

“Party at Jen’s (After the Plague),” by Seattle artist Jennifer Ament. (Zinc Contemporary)

You have plenty of chances to search for that elusive expressive quality in the bountiful crop of figural art on display this month. Pioneer Square newcomer Figure|Ground Gallery is featuring The Nude (Oct. 7-30), a group show of 60 works by a range of artists both emerging and established. “What I find fun about this show,” gallery founder Brett Holverstott says, “is that we have $180,000 art on the wall by seasoned artists next to sketches for $400 by artists for whom this is their first gallery appearance.”

Also naked: the orgy of figures in “Party at Jen’s (After the Plague),” one of many new works by Seattle artist Jennifer Ament on view at Zinc Contemporary in Welcome to Yesterday (Oct. 7-30). Ament’s printmaking background is evident in these boldly graphic works, as well as her insightful sense of humor, as seen in a series of photo-booth style paintings that reveal the personas we choose to put forward in the world.

“Send the Devil Home the Mill is Closing,” by Northwest artist Terry Turrell. (Patricia Rovzar Gallery)

At Patricia Rovzar Gallery, Jagged Edge (through Oct. 28) features the work of self-taught Northwest artist Terry Turrell, whose colorful folk-art-inflected paintings are tightly populated with people and animals. And at Shift Gallery, Seattle ceramicist Sue Springer presents Reflections (Oct. 7-30), showing her playful hand-built humanoid figures, many of which feature tiny drawers and niches — suggesting the secrets we harbor within.

But for a more literal full-body experience, consider Come On In, at On the Boards (Oct. 8- Nov. 6), in which your own person inhabits the art. New York based experimental choreographer Faye Driscoll has created a quiet environment that invites small, timed groups of audience members to step on stage, don headphones, lie on soft benches and follow a series of gentle audio prompts. You might move your hands, sit up or cradle your arms, but, mostly, you are alerted to the feeling of being in a physical body — and a heightened awareness that people among people are always performing.