Earlier today, renowned Northwest sculptor Gerard “Gerry” Tsutakawa stood in the sun and recreated an iconic photo from his artistic past: the day in 1976 when he and his father, the late modernist sculptor George Tsutakawa, together installed the “Memorial Gates” at the north entrance of the Washington Park Arboretum.

“Put your left leg in front of your right,” Arboretum Foundation staff directed. “I need a jean jacket,” Gerry Tsutakawa replied. But replicating the complete 1970s look wasn’t necessary. Seeing him once again standing between the ornamental bronze gates was thrilling enough. Especially since two years ago the gates had disappeared from the park.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

In March 2020, soon after the pandemic “lockdown” was implemented, thieves stole the Memorial Gates one night, leaving only a pair of bolt cutters behind. As a frequent Arboretum walker (even more frequent during those isolated days), I remember the gut punch of seeing the empty posts that had held up the gates for decades. Of course the human toll of the pandemic resonated more loudly, but the pillaging of art added a bleak feeling to an already dark time.

A few days later, the gates — or sections thereof — were discovered. (The perpetrator had tried to sell the bronze pieces as scrap metal.) One had been fully destroyed, a small section of the other was intact. But “even the salvaged piece was damaged,” Gerry Tsutakawa’s wife Judy told me.

Right away, Tsutakawa had said he’d be willing to recreate his dad’s design, which he himself fabricated back in the 1970s. Now a longtime artist in his own right, he worked for 20 years as an apprentice to his father, who died in 1997. The Arboretum raised $160,000 to fund the restoration project.

Gerard “Gerry” Tsutakawa stands with the newly restored “Memorial Gates” in the Washington Park Arboretum. His father, the late George Tsutakawa, designed the original bronze gates, which Gerry fabricated in the 1970s. After those gates were destroyed by thieves in 2020, Gerry refabricated the gates based on his father’s design. (Daniel Spils)

“I’m so relieved,” Gerry Tsutakawa told me this morning, as he watched the new gates being installed. “I’ve been staying up every night worried.” He said that recreating the leaves, pods, vines and compound curves in bronze was no easy task, even though he had his dad’s original drawings. (“He was a packrat,” he noted, with a knowing look.)

The gates — stretching 20 feet across when closed — are made of 150 individual pieces of bronze, each of which had to be cut, welded and finished by hand. “It was a head-scratcher all the way through,” Tsutakawa said. As with the original creation, nothing was done by computer.

Still wrapped in plastic as workers made final adjustments, the gates cast a stained-glass glow on the path where the burbling organic forms made for graceful shadows. The two sections are enormously heavy and will remain open most of the time, welcoming visitors to the grassy shores of Azalea Way — a new location and one much better suited to the artistry than the previous spot, which opened onto the visitor-center parking lot.

With a small group of family and arboretum staff standing by and occasionally dipping into a pink box of celebratory doughnuts, workers closed the gates and moved the orange cones aside. Tsutakawa stepped forward to help remove the plastic. (Watch the unwrapping here.) He pointed out the sections salvaged from the original gates — a portion of circles at the top of the right gate, and on the left, a flat stretch of bronze containing his father’s name.

Next week, the public is invited to a free celebration of the restored gates, featuring food trucks and Taiko drumming at the Washington Park Arboretum on the west side of the Graham Visitors Center (Sept. 14 from 3:30 - 6 p.m.).

“Fountain” (1966), by celebrated Seattle sculptor George Tsutakawa, is one of 75 the artist made over his lifetime. It is functioning and on view at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art. (Brangien Davis/Crosscut)

The elder Tsutakawa is also the subject of an excellent and expansive show at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art. George Tsutakawa: Language of Nature (through Oct. 9) features more than 70 paintings, handbuilt wood furniture pieces, sculptures and a few of his fountains — one of which, shaped like a Brutalist canoe that has sprung a leak, bubbles with water at the entrance of the exhibit.

It’s an eye-opening collection for those most familiar with Tsutakawa’s public fountains, such as “The Fountain of Wisdom” (1960) outside the Seattle Downtown Public Library and “Centennial Fountain” (1989) on the Seattle University campus. In his quest to capture the beauty of flowing water, he created some 75 fountains over his 60-year career, most with his signature Jetsons-mod look. But here we also see the wider range of his works, and how they all hang together.

The show covers Tsutakawa’s art starting in 1950, when he completed his MFA in sculpture at the University of Washington. We see him exploring simple watercolors to portray fish, artichokes and various crustaceans and creating a moody color-blocked self-portrait in oil. His sculptures reflect his particular cocktail of smooth curves and spiky angles, cubism mixed with abstraction mixed with possibly alien flora.

Some of the works look almost animated — see the joy emanating from a blocky bronze sculpture called “Eternal Laughter” (1966). There’s no literal face here, yet we sense a smile. Then there’s the imposing “Evil Eye” (1968), a bronze cone topped with a bronze sphere pierced by a peephole. Apparently Tsutakawa positioned it on the porch of his Mount Baker home in response to the construction of the I-90 bridge, all the better to stare down the concrete scar across Lake Washington.

Even his smaller, quieter sumi-e (black ink paintings) draw you in, such as his take on “Mt. Rainier” (1975). The foreboding black mountain with a black cloud hanging above is a departure from how we usually see the local landmark — and all the more compelling because of it.

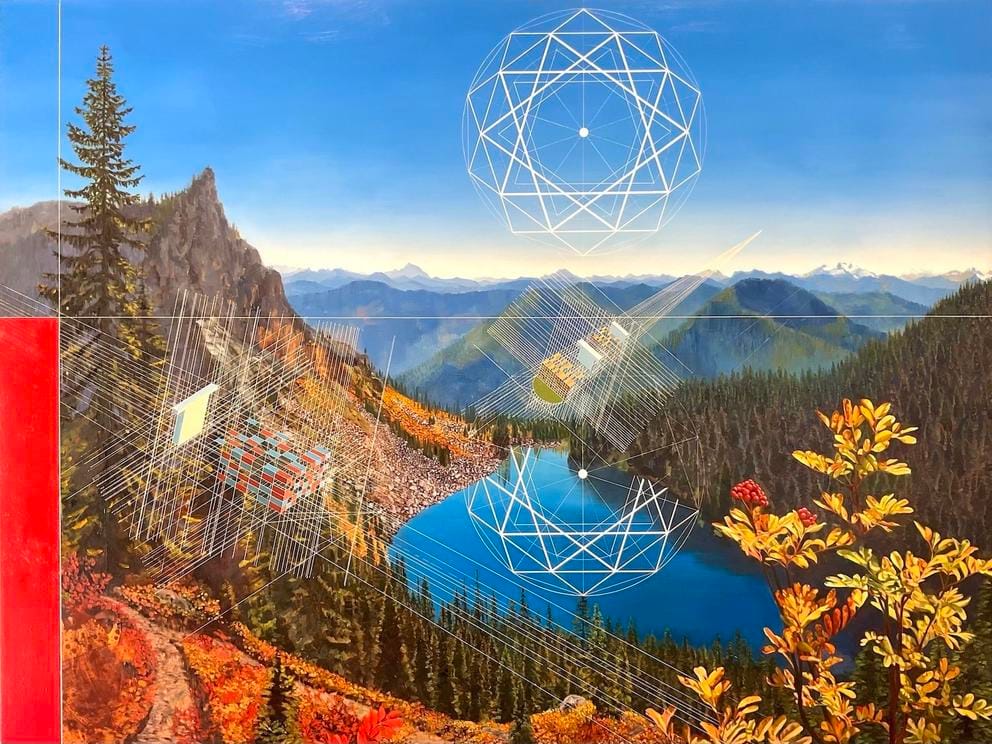

“Lake Above Valhalla,” by Seattle artist Mary Iverson. (Roq La Rue Gallery)

Mount Rainier is looming larger than usual this week, thanks to a mistaken rumor that the volcano was venting. (After a long summer of hosting tourists, who could blame it?) Scientists say not to worry: That waft of “smoke” was only a lenticular cloud. But if the momentary scare has you looking more closely at mountains, you’re in luck: We’re currently experiencing a whole range of mountain art.

At SAM Gallery (adjacent to the Seattle Art Museum gift shop), local painter Ryan Molenkamp presents an homage to the Cascade mountains in Ascendant (artist reception Sept. 11; runs through Oct. 2). These richly colored acrylics emphasize the beauty of geologic strata and tectonic action.

At Roq La Rue in Madison Valley, Seattle artist Mary Iverson is showing Rise and Fall (through Sept. 24), in which she blends traditional landscape painting with linear graphic interruptions that signal environmental danger. But in this show Iverson says she feels a new hope, expressed in paintings such as “Rise and Fall,” which puts a new spin on Myrtle Falls at Mount Rainier National Park.

And in Bellingham, at the Whatcom Museum’s Lightcatcher Building, Holy Mountain (Sept. 10 - Jan. 8), showcases acrylic and oil paintings by Northwest artist Andrea Joyce Heimer, who channels her Montana upbringing into densely packed outdoor imagery. Based on places like Racehorse Falls and Mount Baker, these works are redolent with local lore.