Seattle is a city with a sexual misconduct problem. That’s true of a lot of cities — maybe most of them — including supposed bastions of liberal thought. But in recent months, sexual harassment skeletons have been dragged out of Seattle’s closets, thanks in part to the global Me Too movement and women’s increased willingness to speak out.

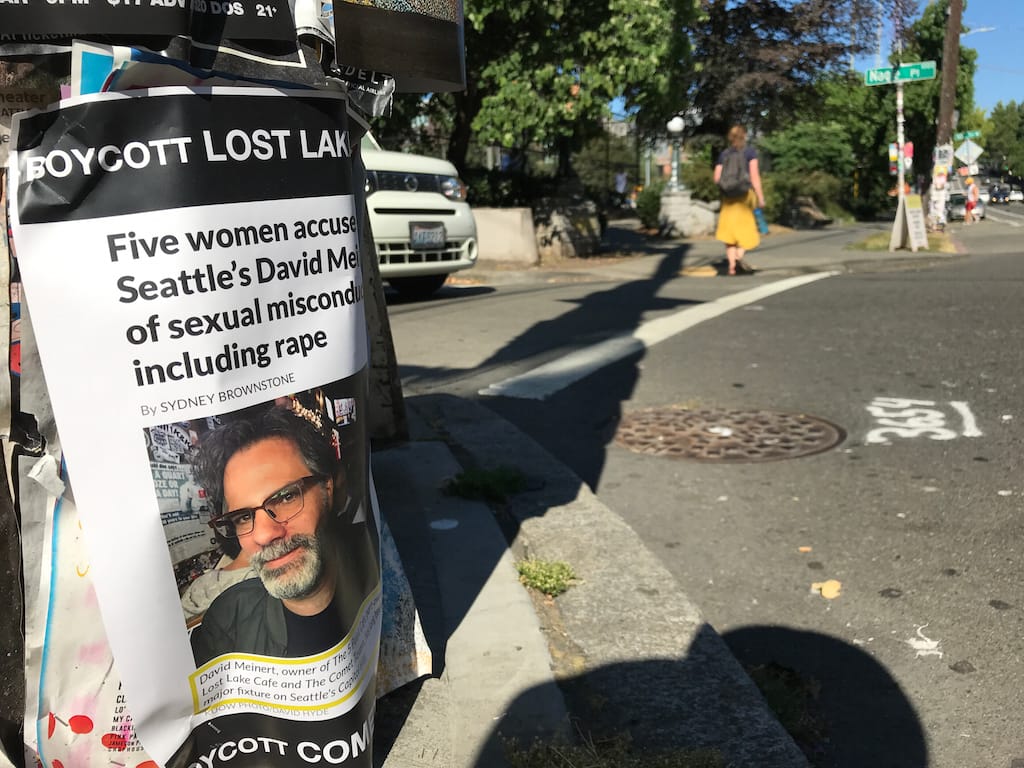

Most recently, KUOW reported allegations of sexual misconduct by local restaurant, bar and music entrepreneur David Meinert. First five women, and in a follow-up story, six more reported incidents of harassment, abuse and rape. Coming as it did on the heels of sexual harassment allegations against local author Sherman Alexie, as reported by NPR, the news seemed to reflect an epidemic of sexual misconduct in Seattle’s cultural scene.

Debates over the best course of action have been raging across town and on social media, with suggestions ranging from “unfriending” Meinert on Facebook to boycotting his restaurants. Local band Tacocat began selling “Ruin Your Local Rapist” t-shirts, with proceeds going to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN).

To find out which issues are front and center in these discussions, Crosscut convened seven Seattle women — all influencers in the restaurant, music and arts communities — for a conversation.

What are the options when women in these industries want to report sexual harassment? How effective is public shaming in altering behavior? How should men be self-policing? Can Seattle, a city of innovation, lead the way in changing the culture that perpetuates sexual misconduct?

This roundtable interview, conducted at Crosscut’s office, has been edited and condensed.

Crosscut: Please introduce yourself and tell us why you’re here.

Om Johari: I was in the band Hell’s Belles when David Meinert was the manager. I'm a musician, producer doing various things around my native hometown.

Angela Stowell: I’m a co-founder and CEO of Ethan Stowell Restaurants and I have worked on a lot of different policy issues in the city. The restaurant groups in town have the luxury of being able to have an HR department. We’ve grown from being very small when we didn’t have HR to very large where we do have HR.

Rachel Marshall: I own Rachel’s Ginger Beer and various other bars on Capitol Hill. When all the Me Too stuff started exploding in December we took some really swift steps because we only have 80 employees and don’t have in-house HR. I have some input on some steps that can be taken when you have a small amount of employees.

Megan Jasper: I’m CEO of Sub Pop Records. We also do not have official HR but we have a lot of fixes for that. We as a company have been talking an awful lot about this stuff that we’re going to be getting into today.

Karen Maeda Allman: I’m one of the author-events coordinators at Elliott Bay Book Company. We also have been hit by Me Too because that’s part of our world, the literary world. We’ve been trying to figure out as a bookstore and as part of the literary community: How do we respond?

Michelle de la Vega: I’m a multidisciplinary artist and a social practice artist. I’m here because over the last few years I’ve done work around this topic. I did a project called The Sugar Project that was a large-scale community engagement project... the thematic arc was the commodification of women. I’ve had a lot of thought around having voice and speaking out and silencing.

Miki Sodos: I’m co-owner of Café Pettirosso and the Bang Bang Café. I’m also a local musician, so I’m involved in the arts. For the most part, I’m a lifelong waitress. I started when I was 17 and I was lucky enough to move up in the industry. It’s been very interesting to hear the dialogue that’s going on with the Me Too movement, with the Shout Your Abortion movement, and women are being more vocal in their experiences.

I’m really excited that people are actually talking about it and realizing that all this stuff that’s happening is so normalized in the music and food industry — you don’t even realize that there is anything wrong with it when you’re a 22-year-old waitress.

Crosscut: Have you seen things in your community changing?

Stowell: We implemented HR when we were at about 200 employees. We want to make sure that the women of this organization feel supported and comfortable... feel like we would have their backs if something was going on. Like you, Miki, I was a server 20 years ago and [harassment] was kind of normal. It was one of those things where I was like, this was part of my job and you dealt with it. I think that in the last six months with Me Too, what we’ve seen is a lot more [employees] coming forth with sometimes smaller issues that maybe aren’t quite …

Marshall: Actionable.

Stowell:… actionable, that is actionable. Definitely, we have had more of an instance of reporting that customers are being inappropriate more than co-workers. We actually implemented a No Drinking policy at our restaurants. Back in the day, everyone got a free shift drink at the end of the night and we’ve really changed our thinking on that. You can’t sit down in the restaurant that you worked at and buy a drink. You can eat dinner; [but] you cannot drink if you’ve worked that night. You can go to another one of our restaurants and enjoy your employee discount as a guest, but you can’t sit around and drink all night because I think that’s when a lot of these things are happening.

Sodos: Yeah, Pettirosso implemented that — no shift drinks — because I like to remain professional. I’m pretty strict on my employees, just from working in the industry for so long. I’m pretty strict because I want to support them in their personal life and not promote alcoholism within the industry, which is so rampant.

One of the things that we did this year, that we’ve never done in 30 years, is we had a harassment workshop program and it was amazing.

Stowell: It’s not like in any other industry. You’re like, “I’m done with my accounting work for today, I’m going to pull up my bottle of booze and sit and drink in the office with all my pals.” That doesn’t happen in other industries, it shouldn’t happen in ours.

Sodos: You don’t have your clients or customers sitting right in front of you thinking all of a sudden they are your friend.

Jasper: In music it’s the same because you are going out, you are in bars. There is drinking everywhere and all the time. One of the things that we did this year, that we’ve never done in 30 years, is we had a harassment workshop program and it was amazing. It was led by a woman who’s a lawyer and she broke down what is harassment, what is not harassment and her focus was sexual harassment. We did two of them with every single employee and we got great feedback.

We have a roundtable here full of women but really the responsibility is on men to change this rape script.

Johari: I just wanted to reiterate the irony about the Me Too movement. Tarana Burke, who started the #MeToo movement in 2006, actually started that hashtag with the intention of putting women of color up front. I think it’s unfortunate that it got co-opted by White female actresses in the movie industry and now everybody is using it. Ultimately, if you're looking at the Indigenous women of this continent and the enslaved women, we’ve been going through 500 years of these kinds of actions. It is clear that the judicial system and the laws are designed to shield and protect White women. Now we have this incident where there’s a White male who is doing particular things to a disproportionate number of White women in the Seattle area, but many of us who are women of color are wondering: If these women had come forward and been women of color, would we be seeing the actions that we see now?

Sodos: I don’t think that it would have gotten so much attention if it wasn’t some of the [specific] women that came forward, you know what I mean? Lower wage women, women of color — these women don’t have options to report; they can’t lose their job, they can’t lose their shift. I don’t think it would have had as much impact if it wasn’t Dave Meinert; if it was just some restaurant worker with a Black waitress it probably wouldn’t have had the effect that it did.

Stowell: I ran into somebody the day before the second article came out and it was a guy. He actually had on a shirt that said “Meinert Threat.” He said that he was selling them at the Pearl Jam concert, but he was like, “I can't believe people have already stopped talking about this.” That that was such a quick news cycle. I think it’s also unfortunate that you have to put your name out there, and that you have to have a recognizable name for it to continue [in the news cycle].

Johari: I think these kinds of conversations are actually difficult to have. We have a roundtable here full of women but really the responsibility is on men to change this rape script.

De la Vega: Because in a way, here we are doing the heavy lifting. Here we are being the teachers.

Johari: I think much the same as with racial tensions and racial issues, when you are trying to set up some sort of workshop, it really needs to come from those people who are dictating the oppression and the power. We need to find out who those people are at the forefront in the nation. Who are male experts that are talking about toxic masculinity and violence? We can have them come to Seattle. Those are the people who can lead this script.

De la Vega: Yeah, I think that actually, the culture is shifting with men. I’ve had a lot of dialogues with men and I see a definite shift from before and after. I was doing this work before Me Too happened and it felt very alone, and I would talk about sexual assault being epidemic and people would think I was so extreme. There is a shift that is starting to happen that I see from men and a level of awareness going on. I think that there's some effectiveness in Me Too.

Is it okay if I jump in and get a little bit personal? It's been an interesting year for me in the sense that I've been involved in this work but it has not made me immune to sexual harassment or sexual assault. I have been dealing with a personal situation and considering how to speak out. I don't want to ruin somebody. [But] I am feeling the sense of responsibility and also wanting to have my own voice heard.

This is a person that’s in [the art community]. [A leader in that community] drafted a letter from a lawyer and submitted that to the person. He also said he was going to create a statement of values for the community and the people who would either have to sign it or agree to it.

I think women have been shamed into silence forever. On the other hand, I feel like we can be motivated out of anger... if we're motivated by hatred and to be destructive … I mean what are our goals? Justice, healing, redemption?

There are a lot of different ways to speak out in our community. Media is one option, that’s what’s been going on with the David Meinert thing and it’s been effective for sure. People are angry at him partially because he’s been unrepentant. I think when people have apologized, people have been willing to give grace and say, “Great, thank you, we’re not not angry, but we don't hate you.”

Sodos: I don’t think he thinks he did anything wrong. I don’t think he’s apologetic.

De la Vega: No, he is not.

Sodos: I think he feels… upset that all this publicity is around his personal life. I think he thinks he was hitting on these chicks and they turned him down and he got a little handsy but I don’t think he actually thinks he did anything wrong. I think that’s why his apology was so shocking because it wasn’t apologetic.

Jasper: It wasn’t an apology, it was defensive.

Sodos: Right, if he’d come out and he was like, “I’m sorry that I made these women feel this way,” I think he would be in a much better situation right now.

Marshall: Does anyone see a downside to the public shaming on Facebook?

Sodos: I think so.

Marshall: It spread so quickly for Dave.

Sodos: Right, I think it’s a good tool for women with a limited scope to use something to help open up their voices. It’s also making one person and a thousand of their Facebook friends judge and juror… and all of a sudden there is no reporting of what happened in the situation. It can be good and bad.

Allman: I think it’s really been tough on our community when women who have spoken out have then left town or were never seen again. It’s like, why do you have to leave?

I mean I understand why people are laying low and leaving, but it’s really terrible to think that that’s the price of speaking out against someone who is a very public person. I think about racist dynamics coming into play as well. I think it’s just really difficult if it’s men of color who are being accused. On the other hand, I believe these women and I would like to see people taking responsibility. There is not a lot of taking responsibility, there is more of these false apologies like Dave’s.

Crosscut: [Filmmaker and activist] Tracy Rector wrote an op-ed after the Sherman Alexie allegations that got at the complexity of a situation in which the accused was also a friend. It’s one thing if you don’t know the perpetrator but what if you do? And what do you do when they’re attached to a work of art or a business you respect?

Johari: I don’t know how many of you actually know Dave but he is also a father of a little girl. I’m concerned and worried about how this backlash is unapologetically attacking him… the baby mother is also involved ... so there is this child who has to deal with what has happened too.

Stowell: Collateral damage.

De la Vega: If he had apologized right off the bat and didn’t hire a public relations manager, it wouldn’t have gotten so huge. Part of the anger he is receiving is due to his denial basically and his lack of humility about it and his lack of willingness to accept. Instead, he’s trying to do damage control.

Something I wanted to get to was the rising power of female business owners and female CEOs in Seattle.

Johari: I think it’s also a human reaction when somebody does something heinous, their first reaction is not to apologize. If you know Dave, then did you expect him to apologize immediately? I mean, let’s look at all the different people of power … Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, you know, these are not guys who automatically just apologize.

Marshall: We’re supposed to extend the scepter to them and say, that’s okay?

Johari: No, not at all. What I think we have to do is find another way. For example, in the music industry, back in the ‘90s, there used to be a group called Ladies Who Lunch and I don’t know what happened to it. To me it was the kind of place where he could have been clocked, he could have been put on point a lot earlier had that group stayed cohesive and super powerful. To me, the solidarity comes with women creating our own consequences and not waiting for said guy to apologize because we think it’s the right thing to do.

Marshall: To your point about female solidarity, something I wanted to get to was the rising power of female business owners and female CEOs in Seattle. I feel like there’s more women who are super successful in restaurants. I’m surrounded by many, many of them and they’re my dearest friends. I love seeing the women in charge.

When I was in my teens I was victimized by a powerful man. He told me I was not going to amount to anything, “You’ll always be a whore.” That put a fire in me to go be as successful as I possibly could, because he said that I was going to be a loser, and it gets me up in the morning. I make decisions about who I’m going to hire. I interview every single person that works with me and I make decisions about vendors that I work with and people whose events I attend based on being victimized. You know, at almost 38 years old I feel more powerful than I have ever felt because I get to make decisions that empower women. We hire as many LGBTQIA people as we possibly can and I give my money to those kinds of organizations. I feel like I have power in a way that I never have.

Stowell: And you’re a mom of boys.

Marshall: I’m a mother of two boys, yeah. I don’t want to make it about me. I just love all these women in the community. I feel like maybe we’re catching up to the dudes very quietly.

And then the question is how do we support men who will speak out on behalf of women?

Sodos: In Seattle, we are in a little bit of an awesome space because there are so many women owners. It’s not just how we feel powerful; it’s also the 22-year-old women who are working for me who feel more powerful.

I don’t really have a lot of sexual harassment in my restaurants because it’s either me or my sister hiring, doing all the firing and men that treat women like that generally aren’t going to be attracted to working for me. Racist people, transphobic people aren’t going to be.

I think the real way that we’re going to fix this is balancing that power.

Marshall: Being the decision makers.

De la Vega: Women speaking out are being decision makers. They’re making the choice, they’re making decisions.

Sodos: For their own life, yeah.

De la Vega: Yes, I think also when we talk about solutions we have to realize each one of these situations is different. I think one thing we should never do is shame women who are speaking out or say that you did the wrong thing by doing that. I have never spoken to a woman yet who does not have a story or multiple stories. It is such an epidemic, it’s so rampant.

Stowell: And then the question is how do we support men who will speak out on behalf of women? We need our male allies to come in and speak out. I think there are probably a lot of really great men who are like, “Oh I made a pass at a woman that one time, I don’t want to speak out because what if that comes back to haunt me?”

How do we empower imperfect people to speak out in a way that isn’t about calling out people’s imperfections? Moving forward, we need to have the conversation, but how can we get our really wonderful male counterparts, friends, brothers, fathers, husbands to have these same conversations and say, “You know what dude, that’s not cool.”

Johari: To do it in spaces where it’s of men, by men, for men, so that they feel like this is a safe space for them to actually say that they made a mistake without feeling like there is somebody there who is judging them and is going to call all their girlfriends and say, “Keep an eye on that one.”

Stowell: Men who lunch, yeah.

De la Vega: We can’t necessarily protect every perpetrator from the shit they’re doing.

Jasper: No, but it has to lead to growth because that’s how things will change.

Jasper: For me, the thing that’s frustrating, specifically around the Dave Meinert stuff, is that I feel like what I’m seeing is a lot of men not speaking out.

Crosscut: Why do you think they aren’t speaking out? Is it because of the fear of imperfection, as in, “If I speak out, everyone is going to attack me?”

Jasper: I think they’re not speaking out for a couple of reasons. I think one of the reasons is what Angela [Stowell] was just talking about, which is that we’re not perfect human beings, so I think there are a lot of men especially in these industries that are grossly forgiving [of other men] in a lot of ways. I think there are some men who feel like if they speak out they are being hypocritical and then I think also, Dave still has an incredible amount of power and it silences a lot of people.