Artist Nick Ferderer was working on a painting in his Belltown studio about a year ago when he suddenly smelled aerosol fumes. “I was like, I’m not spray-painting — what’s going on?” Ferderer recalls. His search took him through the door to the alleyway, where he spotted someone spray-painting 3-foot-tall letters over the abstract exterior mural he’d started a few weeks earlier. He hoped his geometric tessellation of purples and greens could brighten up the building and figured the owners wouldn’t mind. The spray-painter’s contribution was not part of his plan.

After Ferderer told him to leave, the spray-painter walked away — leaving most of the letters just outlined, Ferderer recalled, spelling the name EAGR. Ferderer painted over the tag with white paint that same day, not knowing that EAGR, or EAGER, would come back a few nights later to finish what he started.

“And then,” Ferderer said, “it became a bit of a battle.”

Ferderer isn’t the only person battling EAGER, whose spray-painted name is visible all over the city. Just last month, the Seattle Police Department arrested a man alleged to be EAGER and charged him with a felony for painting on a privately owned Capitol Hill building without permission. The arrest grabbed headlines and the attention of the graffiti community, who saw it as a harbinger of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s new plan to battle graffiti.

Harrell announced his “One Seattle Graffiti Plan” in late October, part of his larger goal to “clean up” and “beautify” the city. The plan — which will include increased graffiti removal and prosecution — is already in motion, and will be rolled out fully this year. Graffiti, Harrell said, detracts “from our city’s vibrancy,” costs small business owners and residents money to remove, and obscures street signage.

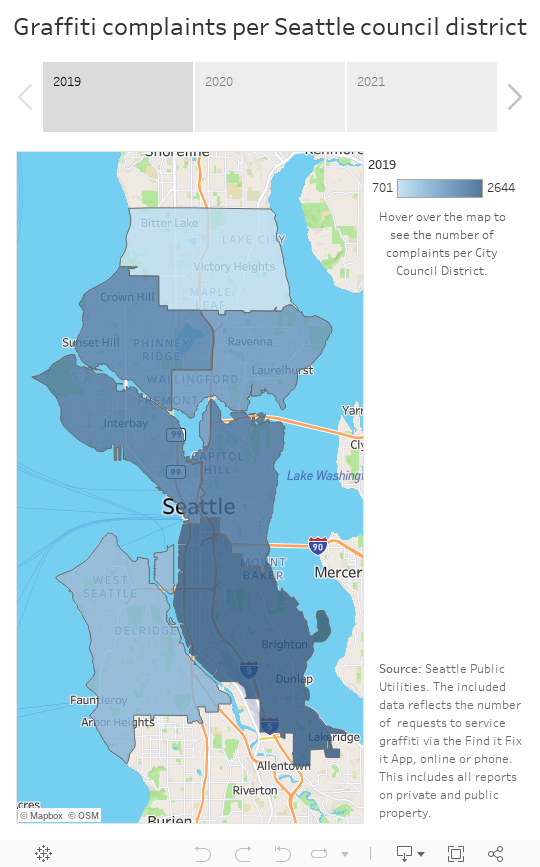

Reports of graffiti, submitted by the public, have grown by more than 50% from 2019 to 2021, according to city data. City agencies cleaned up 8,700 “tags” in 2021, up from 5,000 in 2019.

“At the end of the day, I want a city, a Seattle [where] we’ve mastered the art of expressing kindness toward one another,” Harrell said in an interview with Crosscut last month. “For me, it is not healthy for any human being to deface someone else’s property.”

He also drew a distinction between “unwanted graffiti,” made without consent, and “art,” noting, “It is healthy to express yourself through art.”

During the interview with Crosscut, Harrell stressed that opportunities for graffiti artists to create sanctioned art are central to his plan. At the same time, so is ramping up graffiti removal and prosecution, in collaboration with the City Attorney’s office and the Seattle Police Department.

Harrell’s plan has reopened a decades-old can of worms: Where is the line between artistic expression and vandalism, street art and graffiti, and what role — if any — should the government play in drawing that line?

var divElement = document.getElementById('viz1672801125539'); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName('object')[0]; vizElement.style.width='650px';vizElement.style.height='887px'; var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

Back in Belltown, Ferderer, the painter, grappled with this tension as he strolled through the neighborhood with Tom Graff, a local realtor, commercial property manager and chair of the neighborhood group Belltown United. Graff is sometimes called the “sheriff” because he knows everyone in town and wages a daily paint roller battle against his mortal enemy: graffiti, which he says has exploded in the neighborhood.

“This is not talent. This is destroying brick,” Graff said as he passed some scribbled tags on a wall near Ferderer’s studio.

Colorful and energetic letters burst from the alley’s opposite wall with a 3D effect. Graff said these, in his opinion, could stay — because these were different, creative. Ferderer, a self-professed fan of most graffiti except tagging, jumped in: “But where’s the line? Where do you start accepting it?”

In its essence, graffiti is an act of spontaneous expression and transgression — meaning that graffiti is technically not graffiti when it’s allowed or invited. (Graffiti-style artwork made with permission is usually called “graffiti art” or “graffiti-style art.”) Harrell’s approach treats graffiti as a crime while also trying to enlist graffiti art into the mainstream. The question is whether he can straddle this apparent contradiction.

Graffiti artists have their doubts. In several interviews, graffiti writers (as the people who create graffiti call themselves) challenged the effectiveness of Harrell’s proposed solutions. Graffiti removal — also known as abatement or buffing — isn’t the answer, they say, and neither is more vigorous prosecution.

While some in the graffiti community can get on board with Harrell’s goal to work with artists to create more street art, they say chasing after graffiti is a red herring distracting from the real issues of Seattle’s housing crisis and wealth inequality. Many remain wary and feel left out of Harrell’s plan. Worse, they believe Harrell’s October press conference pitted the public against them.

Seattle muralist Crick Lont, the creator and “ curator” of the pop-up graffiti art space Dozer’s Warehouse, said he urged the Mayor’s office in a call the night before the press conference, “Don’t make it a ‘you vs. us’ thing.” But Lont doesn’t think Harrell succeeded in avoiding that opposition. When the mayor stressed that complaints from the public had swelled to nearly 20,000 and called for more punishment, it felt like a taunt, Lont said. “The graffiti writers are going to be like: ‘20,000 more tags? Guys, let’s do 40!’” he said.

A longtime Seattle graffiti artist who goes by Sneke One said that Harrell should deepen his understanding of local graffiti culture before embarking on his plan. “If he’s really trying to address the graffiti in the streets, he needs to attempt to reach out to those people, not just persecute them and prosecute them … Graffiti writers have a voice [and] are part of the solution as well,” he said.

In the interview with Crosscut, Harrell said he has talked to a lot of people who are trying to combat graffiti, but fewer in the graffiti community, and admitted he could “do a better job there.” In November 2021, Harrell made a similar promise to The Seattle Times, saying “I’m going to first investigate the culture and then I’m going to try to start a relationship with a lot of these folks.”

But some local graffiti writers say that has not happened.

Seattle Parks and Recreation’s graffiti team painted over graffiti on the columns under I-5 at Colonnade Park in November 2022. The park is seen here on Thursday, Dec. 8, 2022, with new tags that popped up a few weeks after the abatement team came through the area. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Game of tag

“Goodbye, EAGER,” a City of Seattle Graffiti Ranger said chipperly, swinging his paint roller toward a knee-high wall overlooking the Dr. José P. Rizal bridge. On the wall, rounded purple block letters, maybe six inches high, spelled out EAGER, and then, again, EAGER. In seconds, the Seattle Public Utilities staffer covered the words with a layer of drab greige paint. “They caught him,” he added with a smile, referring to the recent arrest. “This guy is all over Seattle.”

EAGER was also all over the underside of the bridge, which connects Seattle’s Chinatown-International District to the Beacon Hill neighborhood, in bright, supersized but simple green letters. But the rangers wouldn’t be able to get to that — they had other places to go.

Three pairs of painters spread out across the city Monday through Friday to buff the graffiti citizens have reported (which they can do through a dedicated hotline, online, via the police and the Find it, Fix it app). It’s mostly public property that gets tagged in Seattle; 81% percent of logged graffiti instances in 2021 were on Seattle, King County and other public property, but the rangers help clean up private property as well.

Kevin, a graffiti ranger with the City of Seattle, paints over the tag “Eager” near the Dr. José P. Rizal Bridge on Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2022. The man known as “Eager” was recently arrested and accused of causing thousands of dollars in damage citywide. He has pleaded not guilty. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Today the rangers are focusing on the walls of a small sliver of park near the Dr. José P. Rizal bridge. It’s a “hot spot,” said Stacy Frazier, the painting crew chief with SPU. That means his crew assumes it will get tagged regularly and stops by to repaint it every other week. “We probably could be here once a week,” Frazier said.

Frazier started as a painter with SPU 24 years ago, when the graffiti abatement team, created in 1994, was still in its infancy. Has he noticed a recent uptick in graffiti? “[There’s] not a whole lot more,” Frazier said. “It’s always been this amount … but now there’s just more eyes on it.”

As we speak, two painters, dressed in white pants and high-visibility jackets, move their rollers across the wall to cover human-sized “pieces,” as more intricate graffiti letterings are often called. One, spelling INSITE, is packed with an intricate camo pattern of reds, oranges, pinks and purples — made invisible in a matter of minutes. Where the wall meets the ground, a small horizontal strip accidentally left untouched by the rollers hints at the bright blues and yellows there before.

Even after more than two decades of painting over graffiti, Frazier said he doesn’t get tired of the endless game of tag. “I really don’t. Because I want the taggers to understand that we'll win,” he said. “Even though I know they'll come back and tag it eventually,” he later added.

Graffiti rangers with the City of Seattle paint over recent graffiti under the Dr. José P. Rizal Bridge on Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2022. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Does buffing work?

Harrell said he hopes his plan will break the cycle of tag, buff, tag, buff. But originally, his One Seattle Graffiti Plan and his budget contained a request for more than $1.2 million in extra funding for abatement. The City Council, however — faced with a deep budget shortfall — blocked that spending in a budget amendment vote.

Still, SPU is getting $2.1 million in funding for graffiti inspection and abatement services in 2023. In addition, the Parks Department is receiving $630,000 from the Parks District to create a new five-person “vandalism response team” that will handle graffiti abatement part-time alongside general repair work in city parks.

Stefano Bloch, a professor of cultural geography and critical criminology at the University of Arizona who has long studied (and once practiced) graffiti, said an “aggressive buffing campaign” could be successful. “If a particular area is going to be painted over at six o’clock the next morning, you’re far less likely to waste your time in that area,” he said. “But it also drives graffiti writers to go higher, bigger and out of reach.”

Many Seattle graffiti artists disagree. “I think it’s a pretty generally understood reality that blank walls don’t really stop anything,” said Seattle multidisciplinary and street artist Ezra Dickinson. “They are just blank pages that are asking for people to come and draw on them.”

Sire One, a longtime local graffiti writer, poses in front of a mural he helped curate and create in Fremont on Tuesday, Jan. 3, 2023. While the group didn’t get permission from the property owner, Sire One says he hasn't heard any complaints. Plus, he said: they also cut back brambles and got rid of the garbage surrounding the vacant property. “We look and say: ‘What can we do to make this property look better when we walk away from it besides painting it?’” he said. “The difference it makes for the community is that … they’re not scared of that block anymore,” he added. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Martial art or Renaissance guild?

Graffiti is, technically, a crime. But plenty of people consider it an art form. This is one of the core tensions in a medium filled with contradiction. Few expressions center so heavily on name recognition and absolute anonymity at the same time. The culture is highly competitive, but also built on mutual respect and mentorship. Transgressive and countercultural, graffiti’s aesthetics have been co-opted by the high-end art world, with paintings or even pieces of walls marked by “street artists” changing hands for thousands or millions of dollars.

Seattle painter and muralist Baso Fibonacci, a former graffiti writer, compares graffiti with martial art. “People will be like ninjas going out at night,” he said. As in martial arts, there’s an element of physical and even mental challenge: Mapping a design, planning outlines, shadows, infills and colors at hyperspeed at night takes acuity.

As with sports, the adrenaline rush is a major draw, but there are also rules, such as: Don’t paint over someone’s artwork — including your own — if you can’t paint something superior. Graffiti’s unofficial ranking system is somewhat reminiscent of a video game: Producing more intricate designs (or pieces, as they’re called) with new techniques, hitting a hard-to-reach spot like a billboard or spray-painting your name in simple tags across large spans of territory will command extra respect from graffiti peers.

Often, graffiti writers will work in groups or “crews.” Sire One, a longtime local graffiti writer, equated these with Renaissance art guilds: “You have a tightknit group of friends that work well together and work towards a common goal of creating art for people,” he said.

People outside the community often confuse these crews with gangs. But “the vast overwhelming majority of graffiti in any city in America is not gang-related,” said Bloch. (This is true for Seattle as well: An SPD spokesperson didn’t have numbers available but said “the overwhelming majority of graffiti is not considered gang-related.”)

Similarly, graffiti often gets lumped in with hate speech, according to local graffiti photographer and videographer B. Gnarley (who publishes the Seattle graffiti magazine, BGnarley Underground Arts and Culture). Gnarley said that’s what he felt Harrell did during his press conference back in October. Racist or antisemitic scrawling on the wall? “That’s not graffiti,” he said. “Most of the graffiti writers are just out there writing their names.”

Data backs this up: Only a very small minority — 0.17% — of total graffiti reported to the City in 2021 and 2022 was considered racist, sexist or obscene. The city prioritizes swift removal of this kind of tagging, and is able to abate 100% of it within 24 hours of it being reported.

A Star Wars-themed mural done by DEPTH175 and TWOSICK. Sire One helped curate the murals along the wall. Local graffiti writers and taggers, Sire One said, are predominantly white (as is he). He said he couldn't help but notice that EAGER and SATAN, recently charged with felonies for allegedly creating thousands of dollars in property damage with graffiti, seem to be people of color (judging by their mug shots in the media). “That’s what I’m gonna be watching over time,” Sire One said, “how equitable this plan is.” (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

“Moral panic”

Crime, said Bloch, is another example of something that gets conflated with graffiti. He contends that while it is clear that graffiti does not cause other crime, this association has driven many policies. “Because of the ‘broken windows’ theory, and different ideas about what graffiti symbolizes … law enforcement, District Attorney's offices, homeowners, business owners and the general public are willing to go after graffiti writers for the interpretation of what graffiti is doing to society,” Bloch said. “It all comes back to a moral panic about what graffiti is doing.”

The influential but controversial and, by some measures, disproven “broken windows” theory purports that smaller signs of “disorder” like graffiti or broken windows lead to more serious crimes. It was popularized as a policing approach by New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani in the 1990s, when he cracked down on smaller crimes — including graffiti.

Bloch said he’s seen an ebb and flow of graffiti crackdowns in U.S. cities for decades. “What cities tend to do is, at a time of frustration, or economic downturn, or the perception of increased disorder and criminality, they directly go to the most obvious of all forms of disorder, which is graffiti, and often homelessness. And they point to those things and say, ‘Look, we’re going to stop this. And that will show you that we’re doing our job’,” Bloch said. “And it’s akin to saying: ‘The boss is coming, look busy.’ It’s symbolic.”

Harrell’s current campaign is not the first time Seattle has buckled down on graffiti abatement. Following New York City’s Giuliani-led crackdown on graffiti in the mid-1990s, Seattle passed a “Graffiti Nuisance Ordinance,” a law that requires property owners to remove graffiti from their property within 10 days after notice from the city, punishable by a fine (although fines rarely happen in practice). “Graffiti can be a powerful visual symbol of disorder which erodes public safety,” the ordinance, passed by the City Council in the spring of 1996, reads.

In 2006, then-Mayor Greg Nickels announced his own anti-graffiti effort in his 2007-2008 budget address. Yet another push came a few years later, in 2010, when councilmembers Tom Rasmussen and Tim Burgess requested an audit of the city’s graffiti policies. (Burgess currently serves as Mayor Harrell’s Director of Strategic Initiatives.)

The 2010 request came in response to “feedback from citizens who expressed concern about not feeling safe in their neighborhoods, and their concerns about ‘street disorder’ in Seattle.” In an online survey for the report, roughly 40% of respondents indicated graffiti was a problem and 39% thought it was not. The City of Seattle spent approximately $1.8 million in 2009 abating graffiti from public property. That amount grew to $3.7M in 2022. (Note: This number also contains a small share of abatement on private properties.)

!function(e,i,n,s){var t="InfogramEmbeds",d=e.getElementsByTagName("script")[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement("script");o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src="https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js",d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,"infogram-async");

Harsher punishment

Speaking with Crosscut, Harrell admitted that abatement may be the equivalent of “a dog chasing its tail,” but stressed that his approach wasn’t just about buffing. The plan will also ramp up graffiti enforcement and prosecution.

Harrell said many of these policies are still in development, but he and the City Attorney’s office said they’d prioritize prosecution and seek increased penalties for prolific taggers — whose tags can be found throughout the city and in hard-to-reach spots — including jail time and fines, and diversion programs for others.

“We would like to see programs for low-level graffiti taggers [to] clean up the property damage that they’ve done,” said Anthony Derrick, a spokesperson for the City Attorney’s office. “In order to see a meaningful change on our streets, the city must send a firm message that it will not tolerate continued defacement of our neighborhoods,” Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison said in a statement.

An SPD spokesperson did not directly respond to a question about how its strategy would change, but noted that “the department routinely refocuses and prioritizes efforts to address emerging issues. Graffiti is one such issue.” (SPD has had two graffiti detectives in the past. The most recent one retired in 2020, but the detectives in the general investigations unit still conduct graffiti investigations.)

Just this past month, SPD arrested EAGER, as well as another well-known local graffiti writer, SATAN. The King County prosecutor charged the two men, whom they called “prolific taggers,” with felonies rather than misdemeanors (the usual charge for a graffiti offense) because of the estimated $300,000 in joint property destruction they’ve allegedly caused to Seattle buildings over the years.

Both men had had previous run-ins with the legal system: Casey Lee Cain, aka EAGER, has prior convictions for graffiti, theft and assault; José G. Betancourth, or SATAN, has convictions for the unlawful possession of a firearm and witness tampering, according to charging documents. Both Cain and Betancourth have pleaded not guilty in the current case and were released on bail.

!function(e,i,n,s){var t="InfogramEmbeds",d=e.getElementsByTagName("script")[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement("script");o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src="https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js",d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,"infogram-async");

But Bloch maintains that prosecution and enforcement do not work. “It has never worked. There’s always been graffiti, there’s always going to be graffiti,” he said. “There’s valleys and peaks from era to era, but [enforcement] only manages to further criminalize the very few people who are actually going to get caught doing it.”

Plus, artists say: It’s counterproductive. When graffiti writers are worried about getting chased by police, they have to work fast, leaving less time to paint something intricate or artful that might appeal to a wider audience. Lont of Dozer’s Warehouse said he saw this in action in the creative designs that showed up on the walls of his location: “It’s a way different product than what they do if they’re worried about getting arrested.”

Some academics have also pointed out that criminalization tends to drive graffiti culture more underground, which means that novices miss out on mentorship by experienced writers, which can help younger writers improve their typefaces and techniques or learn about graffiti’s rules of respect for other people’s artworks.

A mural done by Oregon artist CALM, seen on Wednesday, Dec. 28, 2022. Graffiti artists from all over North and South America came to Everett this summer to paint dozens of murals as part of a festival organized by Hype Murals, an Everett-based graffiti-art and mural business. “My sort of pitch that I always gave a building owner or city officials: When a full mural production is put on a wall, in most cases, the graffiti community will understand and there won't be any tagging on that wall,” says Hype Murals founder Brianna Mattes. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Battling graffiti with graffiti

There is one aspect of Harrell’s plan that some local graffiti writers think makes sense: enlisting graffiti artists to do more murals. The City’s Office of Arts & Culture hopes to do this through Spatial Justice Through Street Arts, a $300,000 grant program that will pay “community-based” arts organizations to work with youth — and pay them — to create “street art,” according to the city.

Selected organizations and more details will be made public later this month, but Harrell said he hopes to provide artists with “canvases” like freeway walls and buildings. “Rather [than] someone having to do it at 4 a.m., I’d rather give them some time, some resources to do it, at their own leisure, to beautify the city,” Harrell said.

Translation: The idea is to use graffiti art to battle graffiti, or as Harrell puts it, redirect graffiti writers' energy “into something positive.” This approach has become more popular in recent years in various U.S. cities, and many advocates, including graffiti artists, say it’s more effective at reducing tagging than abatement. But it perpetuates the main debate: Who decides what is beautifying and what is vandalizing?

“So ‘Street art is OK, but graffiti is not OK’ is the message that I’m receiving,” said Sneke One, who regularly does commissioned graffiti-style work but feels conflicted about the city’s art plan. “[Harrell] is kind of gatekeeping in the community.”

That said, Sneke One said more elaborate artwork can be a deterrent for the kind of tags the wider public tends to dislike. Case in point: A graffiti-style mural he painted with the property owner’s consent in Little Saigon — an undulating red dragon supported by yellow “wildstyle” letters on the southern wall of the Khang Hoa Dong supermarket — had remained largely untouched by taggers for three years.

“It got respect from the street, and no one touched it,” Sneke said. The mural, though, was painted over in February of last year amid the launch of a “hot spot” policing approach in response to crime on the corner. Now, Sneke said he sees the wall constantly getting buffed — including by the Mayor as part of a photo op during his One Seattle Day of Service in May — and tagged and buffed again.

“That’s what I always teach the kids: You want to battle graffiti? You have to battle it with graffiti — and you have to do it with better graffiti,” said Sire One. “And then it will take care of 80% of the problems.”

A good example is a painting he recently made with nine other writers on the side of a vacant building in Fremont. At least 100 feet wide, the Star Wars-themed wall features larger painted elements like a stormtrooper helmet and Darth Vader, spacecraft, “freestyle” lettering and a detailed depiction of Yoda wielding a lightsaber. The crew didn’t get permission from the property owner, but worked in daylight over multiple weeks. Sire One said the business owner hasn’t complained, and he hasn’t seen any tags on it since they painted it in October.

That’s not always the case. Murals still get tagged. This often depends on whether taggers respect the artist in question. A slick mural that looks like an ad agency designed it may get tagged, whereas an intricate graffiti-style mural or detailed artwork might be a less likely target. But there are no guarantees. Belltown artist Ferderer (whose mural was tagged by EAGER) says he’s noticed that murals that have been around for a few years may end up getting tagged too — it’s just the lifecycle of urban art.

For a subset of graffiti writers, the fact that graffiti is unwelcome (and illegal) is the attraction and the thrill. They simply don’t want to go mainstream, to sell out.

Brianna Jones-Mattes, owner of Hype Murals, an Everett-based graffiti-art mural business on Wednesday, Dec. 28, 2022. “It’s my desire to educate people” about graffiti, Jones-Mattes said. “And really help a group of artists and a community that I feel has been very stigmatized and demonized.” (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Consider the gum wall

And you’ll never fully eradicate tagging anyway, many graffiti connoisseurs say. “It’s how you grow up in the game, and how you learn and how you grow and how you get your name out there. And every OG or every professional graffiti artist, they started right there,” said Brianna Mattes from Hype Murals, an Everett-based graffiti-art and mural business. “If you want street art, you’ll have to accept tagging.”

Some advocates and academics argue that acceptance, or some form of tolerance, may be key. “Look at the gum wall [in Pike Place Market], for instance: Collectively as a city, we have chosen to take something that, in singular instances, we dislike/reject, and turned it into a weird point of interest in the city,” Dickinson, the street artist, said over text message. Why can’t we do the same with graffiti?

That’s what happened in Bogotá, Colombia, where graffiti was essentially decriminalized following the fatal police shooting of a graffiti writer about a decade ago. While graffiti remains prohibited on culturally significant buildings, monuments and private property without the owner’s permission, fines are rarely issued. Result: The city has become one giant canvas — and a worldwide tourist attraction.

Meanwhile in Seattle, abatement crews are still ensconced in the cycle of buffing and painting.

Two weeks after the SPU rangers painted over the graffiti near the Dr. José P. Rizal bridge, the gray wall now bears a new message. HAPPY NEW YEAR FROM C2D, it reads, in silver three-dimensional capital letters shimmering on purple clouds popping with baubles and sparkles. It’ll get buffed by the end of this month.

Listen to reporter Margo Vansynghel discuss this story on the Crosscut Reports podcast:

Subscribe to Crosscut Reports on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon or wherever you get your podcasts.