Itching to connect with humanity again? Maybe even meet some people outside your pod? Public health officials are still urging us to keep our (social) distance, but on the eve of Independent Bookstore Day (April 24), consider this workaround: read a memoir.

In the absence of spontaneous encounters and in-person conversations, what better way to get to know someone — maybe even get inside their head? We’ve rounded up five new memoirs by Northwest authors, from heartbreaking stories of love in wartime to a fast-paced chronicle of an ascent to stardom. Add them to your spring reading list and you’ll reap a bounty of fruitful new encounters.

Spokane author Kate Lebo's new book is an ode to the unwieldy beauty and hidden dangers of fruit. (Melissa Heale)

A tart, stingy fruit cocktail

Quinces, as Kate Lebo learned years ago, have a way of catching eaters off guard. When biting into the yellow, pear-shaped fruit for the first time, the astringent sourness took her by surprise.

“I stood dumb, cotton-tongued, the quince loose in my hand,” the Spokane author and baker writes in her new essay collection/memoir The Book of Difficult Fruit, an ode to the unwieldy beauty and hidden dangers of berries, grapes, plums and fleshy drupes.

In the book, structured around an alphabet of 26 fruits — from aronia berries to zucchini, “fruit is not the smooth-skinned, bright-hued, waxed and edible ovary of the grocery store,” Lebo writes. Blackberries are colonizers. Chokecherry leaves and seeds contain compounds that become cyanide when ingested. Pomegranates spawned the word “grenade.”

Difficult Fruit is not a traditional memoir (she also shares recipes), but it gradually unpeels Lebo’s personal history. In the cherry chapter, we learn that her aunt died of cancer. In the aronia berries essay, she writes of her mother’s debilitating migraines and her own ulcerative colitis. Later, she measures cancerous lumps (her own, and those of her loved ones’) in blueberry, lingonberry or lychee sizes. Like fruits, our bodies can betray us.

Lebo also branches into wondrous botanical history, art, religion, etymology and mythology to create a lyrical blend that, much like the sweet but tannic pomegranate juice she describes drinking, stirs up “a quenched feeling” of yearning for more.

Translated from Arabic, this aching memoir by Seattle author and filmmaker Mortada Gzar uncoils slowly. (Jonathan Reibsome)

A memoir about love in times of war

“Your next assignment in life is to arrive in Seattle. You’ll find me waiting for you there.”

It wouldn’t be until years after receiving this note from his lover Morise that novelist and journalist Mortada Gzar would leave Iraq, where he — as a gay man and writer — faced unspeakable torture and imprisonment.

Gzar arrived at Sea-Tac Airport on Election Day 2016, after completing a residency at the Iowa International Writers Workshop. This forms the jumping-off place for Gzar’s lyrical new memoir, I’m in Seattle, where are you?

In the book, Gzar — a filmmaker and author of four novels — wanders through the city, telling the story of how he got here in fragmented flashbacks to anyone (or anything) crossing his path: his roommates, a geriatric dog named Heraclitus, statues in Fremont, a person ready to jump off a bridge and even a shoe.

Two men loom large in these memories. The first is Iraq’s then-president Saddam Hussein, who is everywhere: in slogans painted on walls, television programs and, eventually, the towering statue toppled during the American invasion of the country. The second is Gzar’s beloved Morise, an American army officer from Seattle he’d met in Baghdad. Once here, Gzar feels his presence everywhere — even in the shrieks of seagulls and crows crying out “Morise, Morise!”— but doesn't look for him.

Translated from Arabic, this memoir uncoils slowly and leaves us wishing that even the best-told stories had happier endings.

In ther new memoir, local singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile recounts her incredible life story with her signature self-deprecation and congeniality. (Austin Hargrave)

A captivating ascent to fame

If Broken Horses had been fiction, rather than a compelling, entertaining memoir written by Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile, it would be a bit on the nose.

A budding singer, growing up poor and closeted on the outskirts of 1980s Seattle, is infatuated with Elton John and goes on to befriend him as she rises to the top of the charts herself. And then the British pop star dedicates “Tiny Dancer” to her from the stage? Too much! Or that scene where Elton John calls her to congratulate her on snagging six (!) Grammy nominations? I mean, come on.

But that’s what actually happened in Carlile’s unbelievable life, which she recounts with her signature self-deprecation and congeniality. In chronological chapters stuffed with photos, handwritten captions and song lyrics, she takes us back to her hardscrabble childhood in a trailer in Burien and later, moving to 14 different houses, all before high school (though she still found a way to care for a horse).

These early tales give way to coming out, busking at Pike Place Market, trying to make it during open mic nights at the University District’s Rain Dancer bar, spending her money on “guitars, hay and poker” (the hay for a second horse), and, eventually, finding resounding music success and marrying the love of her life. Like a good song, this memoir is captivating through the end and hits all the right notes.

About a quarter-century ago, Seattle journalism professor Sonora Jha swore she would raise "one heck of a feminist son.” She explains how to do that in her new memoir. (Ellie Kozlowski)

A guide to raising tomorrow’s feminists

About a quarter-century ago, after an OB-GYN at an ultrasound clinic in Bangalore happily informed Sonora Jha and her then-husband they’d be having a boy, Jha asked the doc to check again. Then she burst into sobs.

“I wept while my husband rejoiced,” Jha writes in her new memoir/parenting manual How to Raise a Feminist Son. “What would I do with a son? I was afraid. What would he do with me? What if he grew up to be like the men I’d known?” (Later we learn her experiences with men range from professional dismissal to divorce to sexual assault.)

But she took a deep breath. “The next morning, I swore I would raise one heck of a feminist son.”

Twenty-five years on, Jha — a Seattle-based journalism professor and feminist media scholar — shares how to do so by drawing on her own experiences raising a son, as well as research, interviews and conversations with scholars, friends and her own son. In thematic chapters, she unspools both concrete tips as well as the threads of her own life.

She also explains what she wishes she’d done differently, and the things she learned (and unlearned) along the way, including: whatever the ultrasound shows, you may have a trans girl or nonbinary kid. In a sense, despite its title, this book will help anyone hoping to raise a feminist — or even to raise and re-raise yourself as one. As Jha notes, it is a lifelong process.

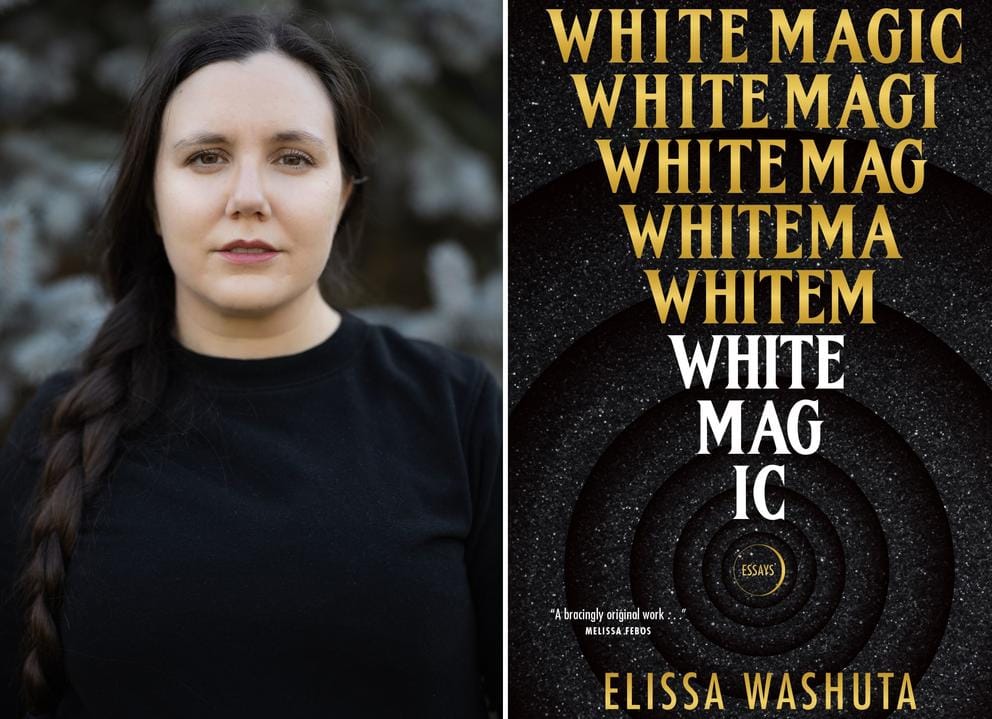

"I just want a version of the occult that isn’t built on plunder, but I suspect that if we could excise the stolen pieces, there would be nothing left," Elissa Washuta writes in her new memoir. (Marcus Jackson)

The magic of writing

For years, Elissa Washuta often called upon the power of tarot cards, photos of ancestors, astrological charts and essential oils. But in 2015, she made a decision: “Chronically drunk and desperate for relief in the Seattle suburbs, I decided the white Wiccans of the web were wrong: I could go it alone and access the power,” she writes in White Magic, her new memoir in essays.

On its face, and in its early essays, the book is about magic and the occult. But the title also refers to the “White City” of Seattle (where Washuta spent many formative years), both in terms of demographics and in reference to a specific event: the temporary renaming of Madison Park as “White City Park,” when it served as an amusement park during the 1909 world’s fair. (One of the essays is partly about this nomenclature.) But in the book’s title, Washuta — a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe who now lives in Ohio — is also nodding to the deceptions of settler-colonialism.

She plays the Oregon Trail II video game and wonders why so many stories are rooted in conquer and plunder. She dissects a Fleetwood Mac video and thinks about her own troubled relationships with white men.

White Magic loops like a woven basket (a structure inspired in part by a visit to the Suquamish museum) and resists neat endings or chronological structure. The ghosts of colonialism and Washuta’s traumas continue to haunt.

In the end, it is not tarot cards but writing — the tedious but magical process of decoding and rebuilding with new tricks and spells — that proves to be the real magic. “When I talk about the book as being about my process of becoming a powerful witch,” Washuta told me during a recent interview, “that's really what I'm talking about.”