This story is part of KCTS 9’s immigration series Borders & Heritage.

Throughout its history, the United States has been a home to immigrants from across the globe who have come here for the promise of freedom and opportunity. Young entrepreneur Fujimatsu Moriguchi arrived in Tacoma in the 1920s, excited about the prospects this new land might offer and the wealth he hoped to bring back to his hometown of Uwajima, Japan.

He had no idea that he would soon be starting what would become one of the leading family-owned retail chains in the Northwest — Uwajimaya — or that he and his family would endure more than three years of forced internment at the hands of the U.S. government.

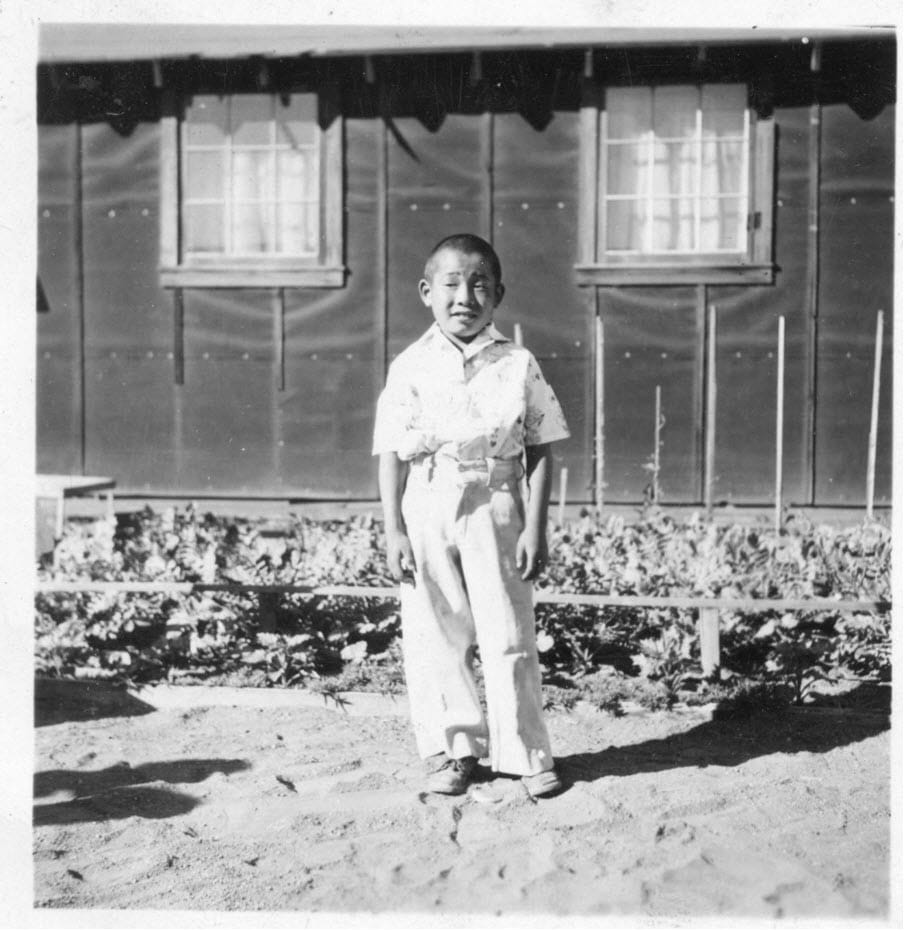

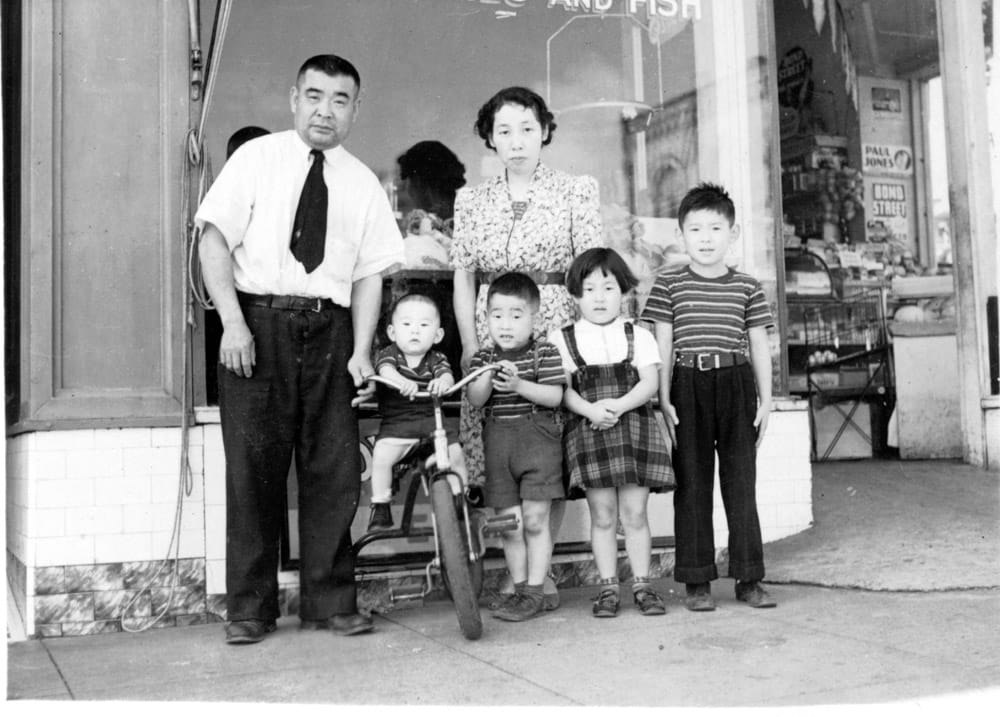

The Moriguchis in 1940 outside their store. Tomio Moriguchi (first row, second from left) remembers driving with his dad to pick up products.

In 1928, Mr. Moriguchi banked that his homemade fish cakes would be his ticket to success in the burgeoning Tacoma logging and fishing camps, which had plenty of homesick, Japanese laborers. He and his wife, Sadako, baked the cakes every evening, and then drove them around the camps throughout the day.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/209303644.jpg?itok=2pIS5Iro","video_url":"https://vimeo.com/209303644","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

Tomio Moriguchi, his second oldest son — now 80 — remembers accompanying his father on his rounds.

“My mother would stay at home and watch the store while my father would put products plus two or three kids in the back of the pickup truck,” says Tomio. “So, my memory was sleeping on the rice in the back of the panel truck during the day.”

The fish cakes were indeed a hit and Uwajimaya, meaning “The Store of Uwajima,” was born. Both the business and the family steadily grew. Then in December of 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, everything began to change. Troubling rumors circulated throughout the camps and the small store near downtown Tacoma.

On Feb. 19, 1942, after much deliberation, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order authorized the Secretary of War to deem areas throughout the West Coast as military zones, clearing the way for more than 120,000 Japanese immigrants — including some 12,800 from Washington State — to be moved to internment camps throughout the west. Uwajimaya shut its doors. In June of 1942, the family was taken to a disbursement center in Puyallup and then south via railcar.

“We didn’t know where we were going,” recalls Tomio. “We were put into a boxcar. I remember the seats were hard wood and the shades were pulled so we got to peek out a little bit. It was an exciting experience. Our parents were with us, so we didn’t feel unsafe. In retrospect we probably should have. We were with friends, neighbors. Later on, the rumor was we were headed for northern California.”

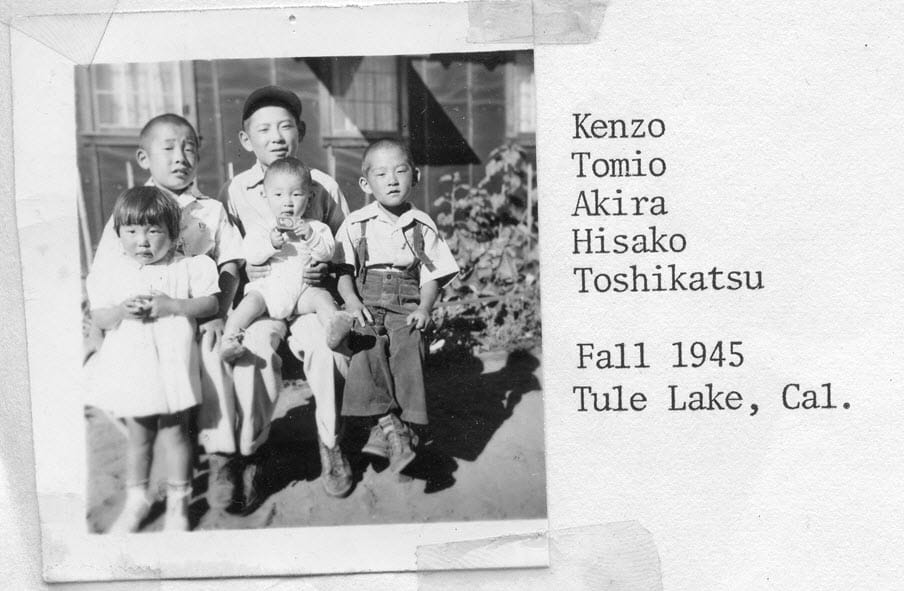

The family was taken to a makeshift assembly center where Sadako — who was 8-and-a-half months pregnant when they left — gave birth to one of the first babies born in internment, a daughter named Hisako.

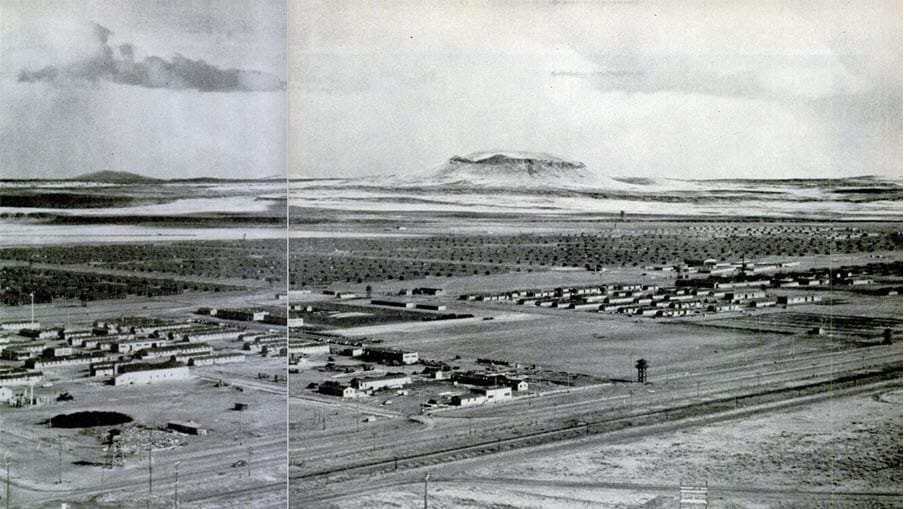

They arrived at Tule Lake, which would soon become the largest of the Internment Camps, later that month. The family, now eight people, was given a 20-by-20 foot room with basic furnishings, which would be their home for the next three years. They soon connected with former customers, friends and extended family, creating a community within the camp that they could rely on.

Hisako’s earliest memories are of the relentless summer heat at the camp.

“It was really, really hot,” Hisako, now 74, remembers. “And I would just sit there and cry. They would put a bowl of ice in front of me with a fan so I would be comfortable.”

During the winter, temperatures dropped to -20 degrees F or lower. The Moriguchis had to be resourceful.

“I remember blankets were cut and made into jackets and things like that,” says Tomio. “Some way they kept us well.”

In 1943 the camp was designated a Maximum Security Segregation Camp that would house those immigrants the government considered the greatest threat to the United States. Dissident prisoners from other camps began arriving in droves and the camp’s population swelled to almost 19,000 people. Many disillusioned Japanese Americans began to protest and challenge their incarceration. The Moriguchis and their close friends tried their best to avoid drawing attention to themselves.

“I was too young to concern myself with democracy or freedom or our constitutional rights and things like that,” recalls Tomio. “People that were older… they dealt with that issue in addition to everything else…. I didn’t know what they were talking about, but as it turns out, that was really galling. It probably, mentally, was more of a stress than the physical hardship.”

The Moriguchi family spent three summers and two winters in the camp, staying past the end of the war for the birth of another daughter, Tomoko, the last of 1,490 babies born at Tule Luke.

“I had such bad eczema that I had not one square inch of skin,” Tomoko, now 71, recalls. “My mother always said that her diet was not good in the camp. So I bled everywhere. They said I looked pathetic. I had no skin, I’m bleeding everywhere. So they would bring me gum. I’m not 3 months old and I had packets and packets of gum — that’s the only thing I remember.” She laughs wryly at the memory.

Through it all, the grit and a tight-knit sense of community helped the Moriguchi family persevere. In late 1945, when they left the camp, Fujimatsu borrowed money from friends and former customers to purchase a new storefront, this time in Seattle. They settled into 422 S. Main St., not far from King Street Station. The entire family began working at the store, making and selling fish cakes and an increasing number of other Japanese and Asian products. The family helped other Japanese Americans returning from internment camps, providing meals, work and advice.

Even as the Moriguchi children endured lingering discrimination in school, Fujimatsu reached out to his connections in the white Seattle business community, participating in trade fairs throughout the region and playing a major role at the 1962 World’s Fair.

As more immigrants arrived in the community around the store, the Moriguchis supported them, too. They were soon a fixture in the growing neighborhood.

“Naturally, the reputation became ‘If you go to Uwajimaya, they will help you,”’ explains Tomio.

Their hard work and community building were a recipe for success, allowing them to open ever-bigger stores, eventually expanding to Bellevue, Renton and Beaverton, Oregon. Both Tomio and Tomoko have served past terms as CEO of the company and continue to be involved with the business. Through it all, they have stuck to the principles and values that kept them together during those trying years at Tule Lake.

“I remember my father saying they did what they had to do — just moved on,” Says Hisako. “‘Look forward, don’t look back’ — I always remember that. Do what you have to do. Make the best of it.”

Today, 75 years after the Executive Order that sent the family to the camp, Uwajimaya continues to be a retail icon in the region, employing some 480 people and preparing to start a new line of smaller retail market locations, the first of which is set to open in South Lake Union this summer. The family has also chosen this year to complete the long-awaited transition of leadership to the third generation.

Denise Moriguchi, only 40 but already an accomplished businesswoman and marketer also grew up working in the Uwajimaya store and retains some of the same values that made her grandfather and her aunts and uncles successful, even in hard times.

“Growing up I didn’t really hear much about the internment from my parents or grandparents,” She explains. “[But] I think having that history does explain my parents’ work ethic.”

“They may not have talked about it but those friendships and relationships… is really how they got through. They were able to persevere and move on with their life and their business.”

The lessons for the present and future are not lost on Denise or the family. “I think especially in today’s environment it’s just really important to remember events like the executive order and the internment of Japanese, just so people are aware that it did happen and that hopefully it will never happen again.”