If you ask local politicos about Washington state’s primary, one phrase will almost always come up — beauty contest.

Washington’s top-two primary system certainly has electoral utility. The cross-partisan scrum allows voters to choose their favorite candidate, regardless of party, and can generate some strange outcomes — like in 2016, where two Republicans advanced in a crowded race for State Treasurer, despite a majority of voters selecting a Democratic candidate on the primary ballot. But the greatest utility of the state primary is perhaps when it’s most useless for selecting nominees: the so-called “beauty contest” races.

Put simply, Washington’s “beauty contests” are races where the primary is less about selecting nominees, and more about gauging how well a nominee performs with actual voters. In some primary races, the nominees are a forgone conclusion. In fact, state law requires that even two-candidate partisan races appear on the primary ballot. That means that many primary races look remarkably like the General Election contest that will follow. And that makes the primary election a sort of semi-representative, semi-random poll with a gigantic sample of actual voters. That’s why Washington’s primary is watched carefully by the parties and analysts: it’s a surprisingly effective predictor of candidates’ viability in the general election.

Given all that, local Republicans should be very nervous after how ugly this year’s beauty contests were. As I have previously written, this month’s primary indicated that the Republicans are at risk to lose up to 40 percent of their state legislative caucus. The picture in congressional races wasn’t much better. Democratic voters also edged out Republicans in Washington’s 8th District, a Clinton-voting open seat being vacated by outgoing GOP Rep. Dave Reichert. That wasn’t a surprise — but Washington Republicans were likely hoping for uncompetitive results in the other congressional districts they currently hold. They didn’t get them.

In the Spokane-based 5th District, incumbent Republican Cathy McMorris Rogers started a little behind Democratic challenger Lisa Brown. Results were similar in southwestern Washington’s 3rd District, with incumbent Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler struggling against Democratic challenger Carolyn Long. While later ballots trended Republican, putting the 5th District especially on the margins of competitiveness, the results were tough enough for the incumbents that both races are likely to become national priorities for both parties.

How is it that these red-leaning districts became national targets? Let’s dive into the results.

District 5

District 5 shouldn’t be competitive. Although it’s perhaps best-known as the home of former House Speaker Tom Foley, whose defeat in the 1994 Republican wave would lead to decades of GOP rule in the district, it was hardly a battleground in 2016. Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in District 5 by a resounding 13 points, 50.3 percent to 37.8 percent. The district — very white, and with many of those vaunted non-college-educated whites — had thus grown more Republican since Romney’s 10-point win in 2012. Moreover, as the highest ranking Republican woman in the House of Representatives, incumbent Cathy McMorris Rodgers is positioned to present herself as a powerful advocate for the 5th District, which faces more economic challenges than Western Washington.

Democrats hoping to pull a reverse-Foley have found their champion in Lisa Brown, Democratic State Senate Majority Speaker and Spokane resident. Brown’s popularity in Spokane County, which casts about 70 percent of the ballots in District 5, is crucial to winning this seat. Brown’s strength as a candidate has drawn national focus. Even then, initial results on primary night — which showed Brown about tied with McMorris Rodgers — made Brown almost seem like a dark horse.

Later ballots have skewed unusually Republican, though. Grouping minor candidates with their partisan matches (e.g., “Trump Populist” with the GOP) shows the Republicans with an advantage of 54.6 percent to 45.4 percent in final ballots. This is a nearly ten-point advantage that would unusually put District 5 on the margins of competitiveness. Nonetheless, political analysts largely rank District 5 as merely Republican-leaning, and the GOP’s 54.6 percent standing is a significant decline from their 2016 general election showing of 59.6 percent. District 5 is worth a look.

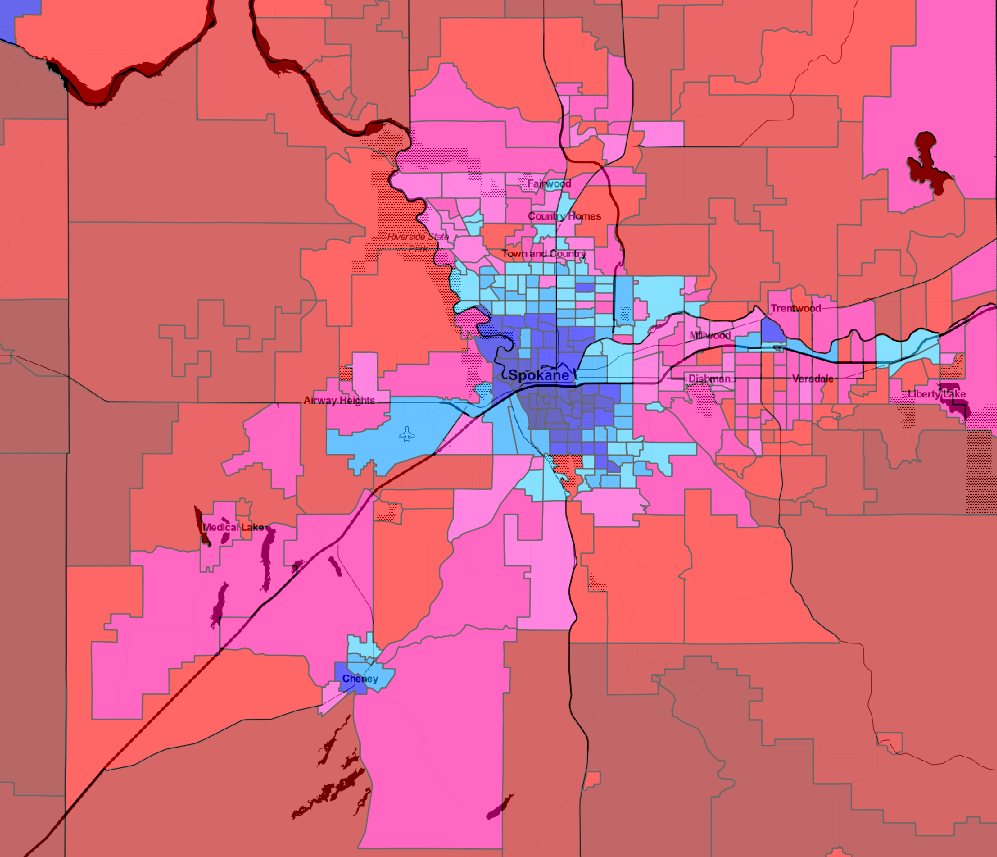

That look — even a close glance, really — makes the division in the district clear. While all ten District 5 counties cast more Republican ballots, Democrats got close enough in Spokane County (48.5 percent of the partisan vote) to keep things competitive. Also helping the Democrats was a close result in Whitman County (49.2 percent), home of Pullman, and respectable showings in Walla Walla County (43.5 percent) and Asotin County (41.7 percent), anchored by working-class Clarkston. Unsurprisingly, the Democrats did even better in each county’s principal cities. Democrats had decisive balloting advantages in the cities of Spokane (59.6 percent) and Pullman (69.8 percent), and they even eked out an advantage in erstwhile-Republican Walla Walla (50.6 percent). District 5’s darkest-blue areas rivaled its darkest-red, too. On Spokane’s South Hill, the well-to-do Manito-Cannon Hill neighborhood was 78.1 percent Democratic.

Even more fascinating was the change between the 2016 general election and the 2018 primary. The Republican line took a big hit in Spokane County, falling from 58.0 percent in the 2016 general to only 51.5 percent in the 2018 primary. In many of the District’s more college-educated neighborhoods, including Spokane’s South Hill, the Republican vote share fell by around 10 percentage points. Republicans also took losses in Asotin, Walla Walla, and Whitman Counties.

However, the story was different in rural Trump Country. There, Republicans held their ground. In McMorris Rogers’ home county of Stevens, for instance, the Republican vote share actually ticked up, going from 67.7 percent to 69.7 percent. The gains were even greater in neighboring Ferry County. The GOP also kept pace in Garfield, Lincoln, and Pend Oreille counties. It appears that McMorris Rogers has bucked the near-universal trend of GOP losses — at least in the deepest-red parts of her district.

Still, though, these rural counties are small. Turnout there was also unexceptional. The absence of rejection should not be confused for the presence of enthusiasm. But, in a tight race, every bit helps. And, with the GOP demonstrating a moderate balloting advantage in the primary, Democrats hoping to turn the 5th District blue will not be able to rely on impressive gains in the District’s urban enclaves alone.

District 3

While McMorris Rogers’ prominent position in the Republican caucus earned her race national attention, it would be fair to say that the incumbent congresswoman in Washington’s 3rd District — Jaime Herrera Beutler — was hoping to keep out of the national fray.

Herrera Beutler, first elected in the GOP-leaning 2010 midterms, has adopted a public posture that reflects southwestern Washington’s historically swingy status. After months of silence, she announced in October 2016 that she would not vote for then-candidate Donald Trump. Since then, she has taken a few public stands that have further irked Trump loyalists. She voted against Obamacare repeal, decried border separations, and rejected the word “alleged” in describing the President’s reported extramarital dalliances. Still, though, Herrera Beutler is a fairly standard Republican. Her “TrumpScore” indicates that she votes with the President’s agenda 91 percent of the time. That’s higher than the “expected” 81 percent, calculated based on her partisanship and the Republican lean of District 3, where Trump prevailed by 7 percentage points.

Despite all of that, the Primary results from the 3rd District ran against conventional wisdom. Most political prognosticators rank McMorris Rogers’ re-election as more endangered than Herrera Beutler’s. But while Republican candidates received 54.6 percent of the final primary vote in the 5th District, the GOP line managed only 50.9 percent in District 3 — a squeaker that would imply an extremely competitive race against winning Democrat Carolyn Long.

Last time, Herrera Beutler received 61.8 percent of the vote. What accounts for her fall to a nearly 50/50 race?

As in the 5th District, the largest county in the 3rd presents the Democrats’ best hope. In Clark County, home to about three-fifths of the District’s voters, Democratic ballots currently represent 53.8 percent of votes cast. That margin is driven by the county seat of Vancouver (61.3 percent), as well as the demographically similar suburban communities of Hazel Dell (60.7 percent) and Salmon Creek (58.1 percent). Notably, many of the Clark County communities that appear to lean toward the Democrat Long were areas where Trump made improvements over Mitt Romney’s 2012 run. Clark County is chockablock with lower-middle-class suburbs with lots of one-floor ramblers but relatively few college degrees. Trump’s 2016 improvements in those precincts do not appear to be echoed in Herrera Beutler’s primary performance, and turnout was largely middling.

The declining Republican vote share in Clark County was even more pronounced in more affluent suburbs. In Camas, a well-heeled bedroom community that gave a respectable victory to Mitt Romney before flipping to a narrower Clinton win in 2016, Democratic ballots represented 58.1 percent of the primary vote. Exurban Ridgefield, where Trump held on to an atrophied seven-point margin over Clinton, also cast more Democratic ballots. These numbers are consistent with continuing GOP bleeding among voters of higher socioeconomic status. They’re also really bad for an incumbent.

In the rest of the 5th District, which leans decisively working-class, results were more mixed. In Cowlitz County, an ancestrally Democratic area where Hillary Clinton absolutely collapsed, Herrera Beutler received a decisive 63.6 percent in the 2016 general — an impressive feat for a Republican. In the primary, Cowlitz County’s congressional vote was only 53.4 percent Republican. However, in longtime Republican areas, Democratic gains were more muted. Lewis County (Centralia), a ruby-red stronghold that reached a new Republican peak in 2016, ticked up from 26 percent Democratic in 2016 to 32.1 percent this year, a much more muted increase than in Clark County. Although it cast fewer than a fifth of Clark County’s vote total, Lewis County remains so Republican than it nearly single-handedly neutralized the Democratic margins in Clark. Still, in the 3rd District’s most Republican areas, turnout was rather anemic.

That sets the 3rd up as a microcosm of national trends. Blue areas are bluer and more energized. Well-heeled suburbanites are punishing the GOP, while more Trump-friendly, working-class suburbs seem disenchanted. In “Trump Country” — where the President remains approved-of — turnout is weak. The combination puts even relatively Trump-skeptical Republicans in GOP-leaning seats, like Herrera Beutler, in surprisingly hot water.

Conclusion

Unlike the up-for-grabs race in District 8, Democrats likely face uphill battles in both the 3rd and 5th Districts. The primary result in the 3rd District was extremely competitive, but Democratic challenger Long is playing catch-up in fundraising and name recognition. And while Brown is perhaps the Democrats’ strongest imaginable candidate in the 5th, the nine-point advantage for Republican ballots in the primary foretells a daunting race.

Still, neither of these districts should be competitive. Both districts voted Trump and weren’t particularly close; and both are represented by Republican incumbents with some history of cross-partisan appeal. If the 8th District is competitive, partisan control of the U.S. House is likely competitive. If the 3rd or 5th Districts are competitive, the U.S. House is likely long gone for the GOP.

At the end of the day, the Republicans are likely to hold both districts. But the results of this month’s “beauty contests” are still very bad news. In a year with plenty of seats to defend, the GOP finds itself on the defense in some surprising places. If the 3rd and 5th District are among the hotter battles in November, there will be little question about which party has won the larger war.