Church bells pealed as parishioners read the names of the 289 deceased. It was an unseasonably dry but frigid night, and the roughly 100 attendees huddled in thick coats in the courtyard outside St. James Cathedral on the border of downtown Seattle and First Hill.

Each person on that list of 289 was a homeless resident of Seattle and King County who had died in the past year. The reading was done outside to remind attendees of the harsh winter conditions that contributed to some of those deaths.

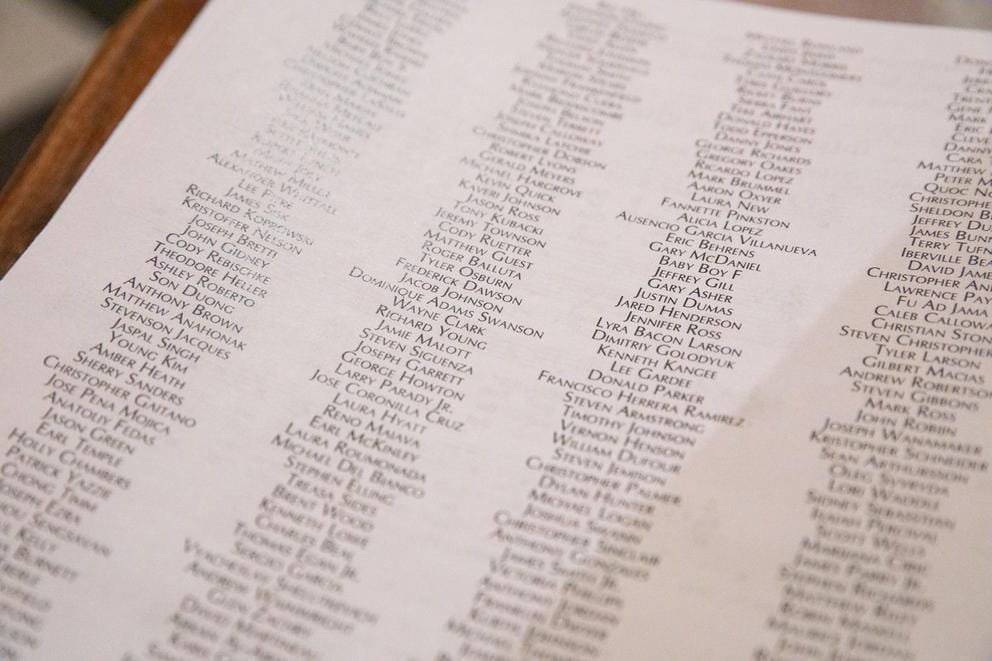

For more than 15 minutes, names rang into the night, an uncomfortable illustration of the growth of the region’s longstanding crisis. Two of the dead were just babies, remembered as “Baby Boy S” and “Baby Boy F.”

St. James Cathedral has been holding its annual Mass for the Deceased Homeless for at least 20 years, according to Patrick Barredo, the cathedral’s director of social outreach and advocacy. It is meant, in the words of Father Michael G. Ryan, to remember “our homeless and poor brothers and sisters” who died on the street and in shelters.

The ceremony began in the warm interior of the ornate, high-domed cathedral with the lighting of 289 candles — one for each person on the list, and a tragic record high number for the church. Last year, St. James recognized the deaths of 221 unhoused people.

Father Ryan then led the congregation in a Mass tailored to the homelessness crisis in our region. In his homily, he said the Mass is not only a remembrance of the dead, but a reminder that as residents of the wealthiest country in the world and one of America’s wealthiest cities, we all share blame for the crisis and should play a role in its resolution.

“May they rest in peace and may we not rest peacefully until we've done everything we can to make this scandal of homelessness our nation's priority, our city's priority, our personal priority, and yes, our sacred mission,” said Father Ryan.

Clergy members pray and listen at St. James Cathedral's Mass honoring the deceased homeless on Thursday, Nov. 10, 2022. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

The 289 people on this year’s list died of illnesses, exposure to the elements, suicide, drug overdoses and violence between October 2021 and September 2022. The median age of death for homeless residents in King County is 51, compared to 79 for all deaths in the area.

According to the King County Medical Examiner’s Office, “accidental deaths” — a category that includes everything from being hit by a car to overdosing — accounted for about half of all homeless deaths in the past decade. Drug overdose and poisoning accounts for about 71% of those. In 2021, accidental deaths increased to 66% of the deaths of unhoused people recorded by the medical examiner.

Ten years of death data shows the racial disparities among King County’s homeless residents. Black residents make up 7% of King County’s population but 14% of deaths of the unhoused. American Indians and Alaska Native make up just 1% of the county population, but 7% of such deaths.

The homeless advocacy and resource nonprofit SHARE/WHEEL gets most of the deceased’s names from the medical examiner and provides them to St. James. SHARE/WHEEL’s list is longer than King County’s because the medical examiner data uses a narrower definition of homelessness than do the advocates or even the federal government.

The medical examiner’s death counts someone as presumed homeless when they are “individuals without permanent housing who lived on the streets or stayed in a shelter, vehicle, or abandoned building at the time preceding death.” Since people living in transitional housing, couch-surfing or similar temporary housing situations are often considered homeless, SHARE/WHEEL draws on other sources within the housing provider and advocate network to complete its list.

The list of 289 names, printed in memory of the homeless people who died over the past year. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

“It's hard to find the right word to describe this. Scandal is certainly one of them. It is a great scandal and a great sadness,” said Father Ryan in his homily. “But even those words fall far short to describe this tragic stain on our city and our region. Despite the declarations of urgency and multiple efforts in both public and private sectors, including, of course, the faith communities, the problems of homelessness, untreated mental illness and rampant drug addiction persists.”

Churches and other religious institutions have long played a role in providing aid to homeless Americans.

St. James Cathedral offers a variety of direct assistance and homeless advocacy. It provides free Sunday breakfast along with dinner Monday through Friday each week. It has a referral center which helps connect people with housing and apply for IDs and pays for some medical bills and prescriptions. The church’s housing-advocacy committee lobbies for affordable housing and homelessness issues at the local, county and state level.

St. James congregants Debbie and Damian Monda attend the Mass for the Deceased Homeless each year. The couple has a personal connection to the event. Debbie said a few of her homeless friends have died over the years, and this year she and Damian recognized several names on the list of the deceased.

“I think, in a lot of cases, [this Mass] is probably the only recognition that most people get when they go through dying on the streets,” said Damian.

St. James Cathedral's Father Michael G. Ryan delivers a sermon dedicated to the deceased homeless of the past year. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

For many years the Mondas have done outreach in Seattle’s homeless encampments, bringing people food and basic supplies and connecting people to services when they ask for that help. They have volunteered with organizations such as Union Gospel Mission and Facing Homelessness. But mostly they just go out on their own.

Some of the most important work, Debbie said, is just about making a personal connection and being consistent.

“We try to always hold ourselves to whatever we [committed to],” she said. “If we say we're coming back tomorrow, we are coming back tomorrow. And that's a huge thing. These people cannot depend on anybody. There's nobody they can trust.”

Barredo, St. James’s advocacy director, said memorial attendance was down this year compared to pre-pandemic levels, and that fewer people are volunteering with the church’s programs for the homeless. He worries that COVID-19 is not to blame, but instead attributes the attendance drop to a sense of exhaustion and despair among Seattle-area residents. The crisis has not only dragged on but worsened since Seattle and King County declared a homelessness state of emergency in 2015.

“To me that signals that there is a lack of hope for change in our society,” said Barredo. “But as people of faith, hope is central to our belief system, and we need to hope there is a better world in store for our brothers and sisters who are on the streets. We will continue to do the work no matter what.”

Damian Monda said he hopes his and Debbie’s outreach can inspire others that anyone can make a difference.

“There's just a lot of opportunity out there for anybody. And I think what we try to model is, without any training, without any psychology degrees or anything, anybody can walk into a homeless camp and, you know, be safe and provide a lot of value,” he said.

Candles are lit in memory of the homeless men, women and children who died in shelters, hospitals and on the streets in the community over the past year. The church said 289 people died. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)