At the 2013 Women Think Next conference in Israel, Microsoft’s head of Human Resources and “chief people person” Lisa Brummel stood before an audience of 500 women who worked in tech. She was wearing a blue button-down shirt: the stereotypical garb of an American businessman.

“I find that men wear these blue shirts all the time,” Brummel said in her opening remarks. “It’s the oddest thing … there’s something about this color blue that keeps cropping up, I don’t know what it is. So my first career advice is please, go buy a blue shirt.”

An openly gay woman at the top of one of the world’s biggest companies until her retirement in December 2014, Brummel’s career path itself made her a pioneer in women’s and LGBT equality. But it’s no secret that the issues of gender imbalances are still well entrenched in the tech field at large – and Microsoft is no exception. According to the company’s most recent diversity report, only 26.8 percent of employees at the company are female. The number dips down to 17.3 percent if you look at leadership positions.

When Brummel addressed the issue of diversity while still at Microsoft, she would always say the “right things”: that the company needs to take it seriously, that the current gender imbalance needs to change. However, unlike Cheryl Sandberg of Facebook, when it came to speaking out on this issue in the world at large, and the changes that could enable women to more effectively climb the corporate ladder, Brummel pretty much kept mum even while she led by example.

But her thoughts on this would have mattered, and not only for her own career. As the person who oversaw Microsoft’s hiring process, Brummel was in a unique position to have significant influence on creating a more balanced employee body. So how does Brummel personally view how being a minority affected her own career, and how did she approach gender issues while at Microsoft?

Now that she speaks as her own person, not as a Microsoft executive advocating for the company, Brummel took the opportunity to discuss her views with us.

One of the boys

As for whether her gender had an effect on her own career, Brummel says it did not.

“I never felt at Microsoft that I was being chosen because I was a woman or that I was in some way being treated differently because I’m a woman,” Brummel told Crosscut.

When she first joined Microsoft in 1989, she actually found the company to be a much more open-minded environment than she had anticipated. Microsoft’s readiness to see the merits of a broad range of skills in employees helped her get ahead, she believes. Taking her first job at the company as a product manager, she had a B.A. in sociology from Yale and an MBA from UCLA — and no background whatsoever in tech.

But a company bringing in a spread of talent is different from a company ensuring a gender balance. One of the attributes that allowed for Brummel to succeed may be that she didn’t care much about the sex of those who surrounded her, so long as they could get the job done.

This was an outlook embraced at an early age, thanks to an interest in sports. These days Brummel is co-owner of the WNBA’s Seattle Storm, and Brummel once had an impressive athletic career out on the courts herself. She lettered in four sports while at Yale, and has even been inducted to two sports halls of fames.

As Brummel was growing up, there were far fewer organized opportunities for girls to play sports than boys—but for her and the three boys in her neighborhood (in Westport, Connecticut, where she grew up in the 1960s), that didn’t matter.

“My sports career is actually a microcosm of diversity,” she says. “The boys didn’t really say ‘you can’t play with us because you’re a girl,’ because I could play with them—I was as good as they were, and in some cases I was better than they were … I mean, we would just all play together … and I really see that carrying all the way through my work career.”

The changing problem

Brummel rose through Microsoft’s ranks in a different time. As Koru CEO Kristen Hamilton told Crosscut earlier this month, gender balance in tech wasn’t part of the conversation in the ‘90s like it is today, because the whole field was just emerging in a Wild West sort of way.

“Early on in tech it was every engineer for themselves,” Brummel says. It was a time of individualism for which Brummel’s tenacious personality may have been particularly well suited. But, as the field of tech expands, it is figuring out this kind of gender blindness might not be the best thing for its own longevity, because there’s evidence the blindness is not actually real.

“Now it’s a lot more, ‘Hey, we have to work together as a team to be successful,’” Brummel says.

Which may be why there is more conversation about women in tech now than there was two decades ago. If the goal is building a team that can work together, it’s impossible to get around the fact that society statistically treats women very differently from men in the workplace: in terms of who gets the education to be qualified for the job; given equal qualifications, in terms of which candidate gets the job; given equal job status, in terms of who gets the promotion and raise. If the goal is to make employees feel equally valued regardless of gender, then it’s clearly not working.

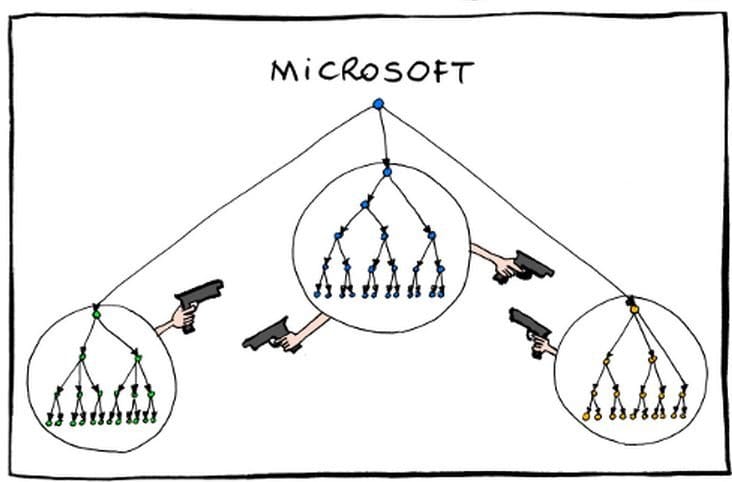

And Microsoft has left room for doubt that the company’s policies are unbiased. One past practice (no longer in place) that led to claims of gender discrimination is associated with Brummel herself: the system of stack ranking.

For many years, “stack ranking” was Microsoft’s company-wide employee review process, in which supervisors were required to rate all of their employees from 1 to 5 on a curve, with a fixed proportion of employees receiving each rating. This essentially meant that a certain proportion of every team’s members had to be marked as bad at their job, on track for a firing.

It was discontinued in November 2013, when Brummel was still at Microsoft. But when she took her position as their HR architect in 2005, she made promises to fix it. Instead, many believe the changes she made to the system made it worse – leading at least one employee to call her “the most universally hated exec at Microsoft.”

A class action lawsuit filed by former Microsoft employee Katie Moussouris in September 2015, claimed that the system particularly harmed women at the company.

“The stack ranking process systematically undervalued female technical employees compared to similarly suited male employees because, among other reasons, it meant that lower ranked employees were inferior and should be paid less and promoted less frequently regardless of their actual contributions to Microsoft,” the suit reads.

“Upon information and belief, female technical employees tended to receive lower scores than their male peers, despite having had equal or better performance during the same performance period.”

Kinks in the pipeline?

But would another employee review process have worked any more fairly? Or are gender biases and discriminations so engrained that they would have found a different way to manifest?

Brummel’s main role was to look after the best interests of the company, she says. While she is glad that Microsoft has since moved on to a different system, she stands by the premise that stack ranking was the right approach for its time.

“If you have a fixed amount of money and you have a fixed set of skills, and people have a sense of ‘Hey, I want to work for my next thing,’ there’s always going to be a way of deciding how you want to allocate money,” she says.

Similarly, when it comes to hiring, Microsoft’s goal was to attract the top talent available to them. Should the company go out of its way to employ more women even if, due to greater social circumstances – a.k.a. the “pipeline problem” – there are simply fewer women within the applicant pool from which to choose?

At the end of the day, Brummel says good products are the goal, and the type of people who create them is secondary: “We were on a mission to get technology to people,” she says. “And anybody who wanted to be on that mission was somebody we would consider bringing into the company.”

Clearing “the big bar”

At the same time, Brummel has openly spoken about the ways in which increased employee diversity would be a boon to the company. In response to the diversity statistics that were released in October 2014 (while she was still at the company), she wrote an email to all full-time employees:

Diversity and inclusion are a business imperative. Diversity needs to be a source of strength and competitive advantage to us. Our customer base is increasingly diverse. As our business evolves to focus more on end-to-end customer experiences, having a diverse employee base will better position Microsoft to anticipate, respond to and serve the needs of the changing marketplace.

And representation itself is not enough – we must also create an inclusive work environment that enables us to capitalize on the diverse perspectives, ideas and innovative solutions of our employees.

There is no easy fix for creating a more equal tech sector, or easy way to figure out who’s responsible for taking the helm in doing so. Many feminist thought leaders in the industry, such as Sandberg, have put a fair amount of the onus on women to be the ones to “lean in.” Doing so seems to have come naturally to Brummel – and it certainly worked for her, so it makes sense that she would give similar advice.

“When I was at Microsoft, I spoke a lot about confidence, particularly to women, because I think it’s hard when you’re in the minority,” Brummel says. “I always told people, ‘Hey, you’re at Microsoft. You jumped over a very big bar to get here. It’s worked for you – remember that.’”

But, as described in a blog post by software engineer Kate Heddleston last year, even the women who jump that bar find that there are other factors – issues like flextime, parental leave, sexual harassment, and the wage gap, for example – that might, over time, cause their own gumption to fizzle out:

Women in tech are the canary in the coal mine. Normally when the canary in the coal mine starts dying you know the environment is toxic and you should get the hell out. Instead, the tech industry is looking at the canary, wondering why it can’t breath, saying “Lean in, canary. Lean in!” When one canary dies they get a new one because getting more canaries is how you fix the lack of canaries, right? Except the problem is that there isn’t enough oxygen in the coal mine, not that there are too few canaries.

Maybe some women do find that the proverbial blue shirt fits them best. Brummel fits this mold, and has been very successful. But it’s time for the tech industry to start fitting itself around what many women find important, too, in whatever cut and color of clothing they choose to show up.