On December 3, 1917, a young woman stood before a Seattle judge and gathered her notes to address the jury and spectators. The courtroom audience was standing room only – silent, waiting, attentive. She spoke for an hour in a clear, ringing voice, and declared:

Life in the United States today is at the mercy of war-mad fanatics… Today, if we would remain out of jail, [we must] seal our lips and lay our pens aside, and submit to seeing our dearest ideals of freedom and human dignity dragged through the blood and dust of a war for financial profit….

But even though every conscientious objector, every pacifist, and every [Industrial Worker of the World] be thrown into jail, [their ideas] will go on because ideas cannot be imprisoned!

With these extraordinary words, Louise Olivereau concluded her trial for sedition on the World War I homefront. She stood accused of using the mails to distribute thousands of leaflets encouraging young men to evade the draft as conscientious objectors, in violation of the Espionage Act. Olivereau had declined an attorney and represented herself throughout the trial, freely admitting that she had written, mimeographed, and mailed the leaflets. Now, she awaited her sentence.

---

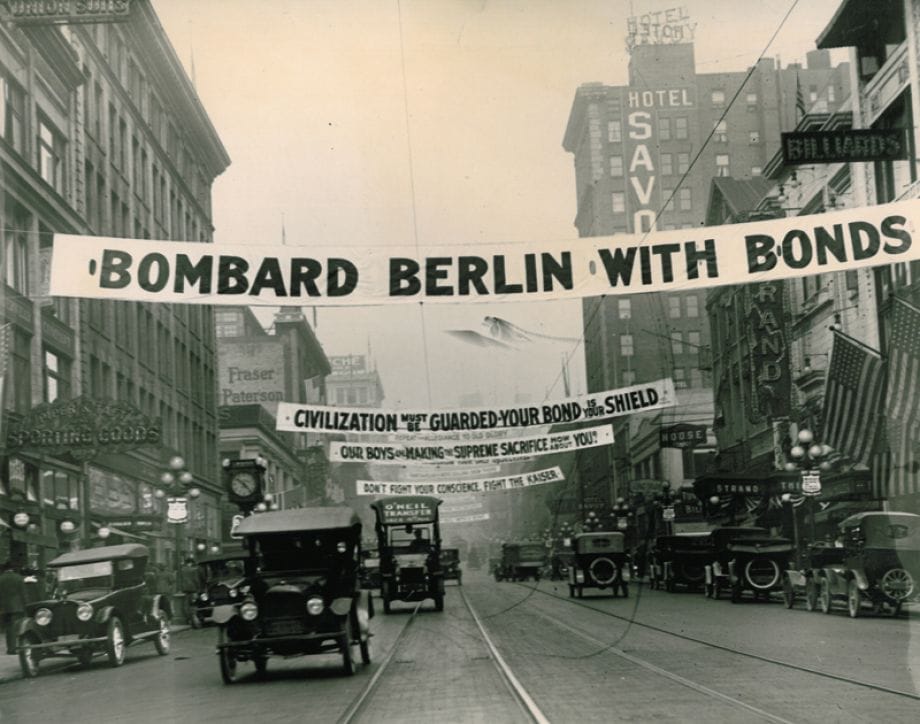

The United States entered World War I eight months before Olivereau’s trial - on April 6, 1917 - mobilizing American industry for military production. This included Seattle’s shipyards and the year-old Boeing Company, then known as Pacific Aero Products. Government posters encouraged Americans to tighten their belts, conserving food through Meatless Tuesdays and Wheatless Mondays; Washington voters had already passed a Prohibition initiative, in part to conserve grain.

In May 1917, the U.S. Congress enacted Selective Service, requiring young men to register with their local draft board, to await conscription. But in Seattle, there was significant opposition to involvement in this war from German-Americans, from Irish-Americans, from organized labor, and from Socialists. As one Socialist periodical put it:

The American people did not and do not want this war. They have not been consulted about the war and have had no part in declaring war. They have been plunged into war by the trickery and treachery of the ruling class of this country through its political representatives, its demagogic agitators, its subsidized press and other servile instruments of public expression.

-American Socialist, April 21, 1917

Those who supported the war viewed such statements as disloyal and dangerous, likely made by pro-German sympathizers or untrustworthy immigrants - “hyphenated Americans.” The war encouraged the hyper-patriotism known as jingoism and the hyper-paranoia known as xenophobia. During the war, German composer Richard Wagner’s music wasn’t played by Seattle orchestras, and local high schools, colleges, and the University of Washington stopped offering classes in the German language.

But not everyone quietly accepted the pervasive homefront pressures. In 1917, metro Seattle was lively with non-conformists who opposed the war, from a wide range of perspectives. A variety of cooperative settlements had sprung up on the shores of Puget Sound, offering alternative ways of life, from free love to common property. Local Socialists were numerous and vocal in Seattle politics. The major Seattle anti-war, pro-labor newspaper, the Union Record, boasted the impressive circulation of 112,000 readers, in 1918.

But the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) – also known as the “Wobblies” – were the noisiest opponents of World War I, condemning it as a rich man’s war for poor men to die in. The IWW recruited well in Washington State, appealing to the single, footloose men who worked in the dreadful conditions of the mines, mills, and woods. The Wobblies called for One Big Union and One Big Strike to abolish the wage system, destroy capitalism, and redistribute industrial wealth.

After the Russian revolution, accusations that the Wobblies were backed by pro-German sympathizers were replaced by accusations that they were financed by the Bolsheviks. During the summer of 1917, the IWW went on strike in the Washington state woods, where the U.S. Army was harvesting spruce for airplane construction. As the homefront majority spoke in favor of preparedness and war, and as young American men began to die in the trenches of France, Wobblies and other anti-war activists were increasingly criminalized.

In June 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, intended to punish pro-German saboteurs, spies, and propagandists. It instead became a tool to silence all opposition to the war. The Act outlawed any attempt to “cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States,” and prohibited any criticism of the war effort. In effect, dissent became a crime on the World War I homefront.

A military march down Seattle’s Second Avenue.

---

Dissident Louise Olivereau was born and grew up in Wyoming. She attended college in Illinois, and left school to move from job to job in the American West, working as a stenographer in Salt Lake City and Portland, and cooking in Northwest logging camps. In 1915, she moved to Seattle, went to work for the IWW, and rented rooms in a house in Wallingford. She loved to hike, she was a scholar of the plays of Henrik Ibsen; she formed deep and lasting friendships with local radical women like Minnie Parkhurst and Anna Louise Strong. At her Wallingford apartment, she hosted a small study group, leading discussions on poetry, philosophy and the theater.

In July 1917, Olivereau was 33, a stenographer in the Wobblies’ Seattle office. She arrived in Seattle a socialist but soon came to consider herself an anarchist, convinced that the individual could best think, choose, and act without the restraint of government. The Socialist Party seemed too political to Olivereau and others who shared her principles – they scorned “ballot-box Socialists” who were ambitious for office, their ideals compromised by the political process. By the summer of 1917, Olivereau can be documented attending nearly every anti-war rally in Seattle with her close friend Minnie Parkhurst.

It was a statement by former U.S. Senator from New York Elihu Root that eventually incensed Olivereau to more direct action. Speaking in Seattle, Root declared that it was unpatriotic to argue about the cause of the war, or to question whether the U.S. should have entered it. To Olivereau, the senator was prohibiting inquiry and discussion, making the act of thinking a crime.

Olivereau struck back in her own way. She composed and distributed a flyer to the young men called up for induction into the U.S. Army. Each week, the Seattle Times and the Seattle Star published the names of men who had been conscripted. Olivereau simply looked up their addresses in the city directories, and took the step that would lead to her arrest, trial, and conviction as a traitor.

Citing Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain, and Thomas Jefferson, Olivereau argued in the flyers that each conscript must be free to think for himself and obey his own conscience, concluding: “What are these abstract sentiments of liberty, freedom, justice and independence worth to us, if we must be slaves to preserve them for our masters?”

At a time when her weekly wages were $15, Olivereau spent about $40 on her anti-war campaign, mailing approximately 2000 flyers at different Seattle mailboxes in August and September, 1917. The use of the postal system for distribution of messages encouraging conscientious objection to military service was forbidden by the Espionage Act and carried heavy penalties. Olivereau was undoubtedly aware of the risk.

On September 5, federal agents raided the Seattle IWW offices, boxing up and carting away all correspondence, books, pamphlets, and periodicals – even a framed map of Washington that hung on the wall. When Olivereau arrived at work, she found that her desk had been cleaned out. She paid a visit to Howard Wright, special agent for the Department of Justice, and asked for her books to be returned.

A military march on Seattle’s Third Avenue and Madison Street.

---

Wright showed her one of the anti-conscription flyers, and asked whether it had been produced at the IWW office. Olivereau denied it. From Wright’s office, the pair walked to U.S. District Attorney Clay Allen’s office, and went on to visit Seattle’s postal inspector, Charles Perkins. Perkins had a stack of the flyers on his table and asked whether she had written them; she denied authorship.

But when Perkins read a letter that Olivereau had mailed to a co-conspirator in Bellingham, asking him to circulate some flyers, she admitted authorship but insisted she had acted on her own, denying any involvement by the IWW. Wright, Allen, and Perkins then accompanied Olivereau on the streetcar to her Wallingford home, where she showed them some unmailed flyers. Olivereau was arrested on the spot for violation of the Espionage Act. Bail was set at $7500, which she could not raise.

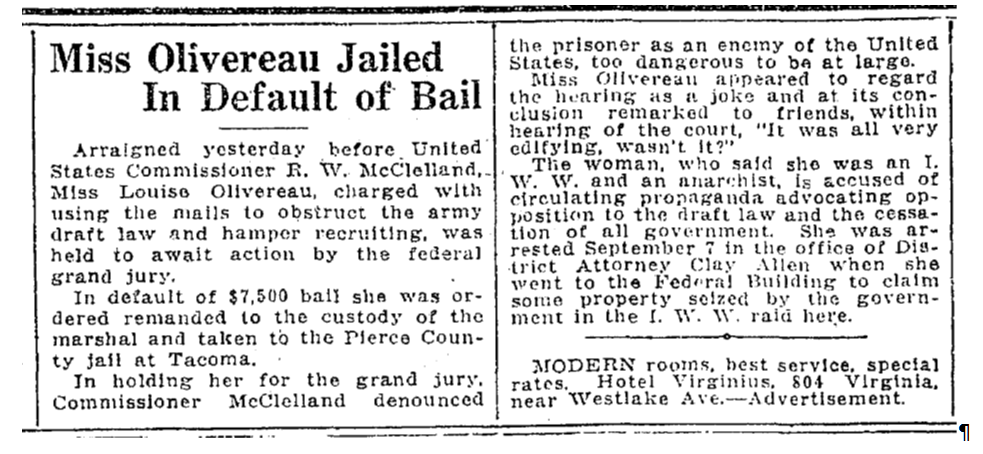

At her arraignment on November 12, she was declared “an enemy of the United States, too dangerous to be at large,” charged with composing, printing, and mailing flyers intended to cause “insurrection and treason and sedition.”

Her arrest was front page news – a Seattle traitor! - and local newspapers breathlessly followed her brief trial, though reporting was fractured along ideological lines. The Socialist Daily Call published Olivereau’s proud remark, “I expected to pay the price,” and reported that she was satisfied that she had acted as her convictions required. The Seattle Times reporter was shocked that she “appeared to regard [her arraignment] hearing as a joke,” remarking loudly to friends, “It was all very edifying, wasn’t it?”

According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the caption for this photo at the time of publication read: “Crowds cheering, bands blaring, flags flying, Naval cadets march down a Seattle street during wartime. Luckily these boys never learned in combat that war is not all cheering crowds, blaring bands, flying flags, but rather a ruthless struggle to kill, to live in the midst of death.”

The Times expected Olivereau to be timid, frail, and penitent – she wasn’t. On November 1, the Times announced 38 indictments against “slackers” who refused to register under the Selective Service Act or resisted induction, and the radicals and conspirators who encouraged them. Louise Olivereau was charged with nine counts of violating the Espionage Act. She declined the representation of an attorney and pled not guilty.

Olivereau was not a lawyer, and defended herself on the basis of ideals, not the law. Judge Jeremiah Neterer was clearly frustrated by her naïve questions of principle to jurors and witnesses, and forbade her asking her jurors whether they believed in freedom of speech and of the press in wartime, and whether they believed an individual had a right to criticize the government.

Neterer used the legal system to shut down as much courtroom drama as he could. But Olivereau confidently took center stage, freely admitting that she was a Wobbly and an anarchist “with a show of pride,” and often showing her disgust with the trial proceedings, according to the Times. Olivereau was playing to the house.

---

One of her courtroom supporters was Anna Louise Strong, already the subject of recall petitions as a member of the Seattle School Board. The Committee of Spanish-American War Veterans, leading the recall, noted that Strong “was in open sympathy with enemies of the government.” She was seated in the front row at the Olivereau trial, and walked arm-in-arm with the defendant during the breaks. The Committee press release continued “[Strong] has appeared in public to befriend the IWW, the pacifists, the conscientious objectors, circulators of anti-draft literature and [now] lends aid and comfort to a self-confessed anarchist.”

Strong retorted that Olivereau had spent “her last cent” to publish and mail her flyers, that she “was courageously true… and meant no harm to any living soul.”

Olivereau’s closing remarks, quoted at the head of this article, recounted the events leading to her arrest and also explored her ideology. She stood alone before the court, and her voice rang out – “deep, clear and her words chosen for effect,” according to the Post-Intelligencer. She said that she had “no use” for the United States government, and compared it with “the militaristic system of Germany we are fighting.” She spoke, too, to her feminist principles:

Consider that in this democratic country millions of women are denied so simple a democratic right as the ballot….Consider also that other women have been jailed…for advocating that women should have the right of voluntary motherhood and for teaching the women of the very poor how to lessen their misery by limiting the size of their families….

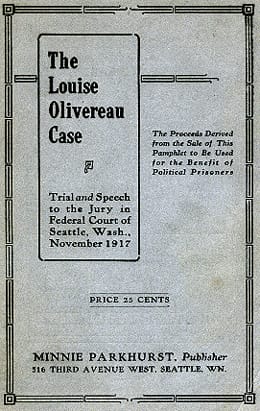

In choosing to conduct her own defense, Olivereau knew that she would have this one chance to address the court at length, to publicly speak her mind. That opportunity made her punishment meaningful to her. When she had concluded her hour-long speech, the jurors filed out. They deliberated for less than half an hour to find her guilty.

Louise Olivereau’s hasty trial began on November 28 and she was sentenced on December 3, 1917, to ten years in federal prison. She received the sentence without comment; she didn’t seem surprised. Since McNeil Island federal prison had no provision for female inmates, she was sent to serve her sentence at the Colorado State Penitentiary, at Canon City, Colorado.

During her 28 months in prison, Olivereau corresponded with Minnie Parkhurst and others, her letters censored, their content redacted with heavy black lines. Olivereau’s sister, back in Wyoming, asked that their correspondence cease because of the family’s embarrassment at her criminal behavior. Anna Louise Strong backed away from her friendship with Olivereau, but she was recalled from the Seattle School Board nevertheless. Forbidden to discuss politics, pacifism or international affairs, Olivereau’s voice was muted in her letters to Parkhurst, the voice of an imprisoned woman who was a political prisoner.

Olivereau initially hoped for a successful appeal and a quick release. But having acted as her own legal counsel, she hadn’t realized that she needed to file an act of demurrer immediately at the conclusion of her trial. So, no appeal.

At first, she wrote to Parkhurst and kept herself busy in prison. Olivereau cultivated a small garden plot, taught shorthand, and tutored her fellow inmates in English grammar. Much of her time was devoted to sending letters to raise money to publish a transcript of her Seattle trial. Parkhurst took on this crusade, advertising for funds throughout the radical press, encouraging donations to document “the trial of a woman found guilty of thinking.”

The pamphlet was not published for a year, due to the reluctance of local printing houses to be associated with such an inflammatory woman and such a sensational topic. In prison, the months dragged on, and Olivereau grew tired of her garden and the shorthand class. She wrote to Parkhurst:

The flat monotony and lack of any big interest or motive of any kind is hard to bear – but I’m not complaining because, of course, I knew what the price was before I incurred the debt.

Time seemed to stand still for Olivereau in prison, though life went on back in Seattle and out in the world. In October 1917, the Bolshevik revolution had swept away the tsarist monarchy and offered radicals worldwide their first experimental workers’ state. American Prohibition continued, and Seattle had more than its fair share of rumrunners, bootleggers, and crooked cops. The world was ravaged by an influenza epidemic that claimed more lives than the bloody war.

World War I ended on November 11, 1918. Instantly, military contracts were cancelled for mobilized war industries in Seattle, and thousands were unemployed. Sixty thousand Seattle workers withdrew their labor for three days in the General Strike of 1919. Fear of the Bolshevik replaced fear of the German, and America’s Great Red Scare began with raids, trials, and deportations. During the Centralia, WA commemoration of the Armistice in 1919, three members of the American Legion were shot to death on parade, and a Wobbly was lynched by vigilantes in retaliation. In 1920, the 19th amendment to the Constitution was passed, giving American women the vote in federal elections.

---

Louise Olivereau was released on March 25, 1920, finding the world had changed, and a new jazz age of fast cars, hip flasks, and short skirts had arrived. She returned by train to Seattle, stayed briefly, and then went on to Portland, Oregon. She worked as a stenographer in a law office, and spoke publicly about the grim conditions at the Canon City penitentiary. She also spoke about her trial and sold copies of the pamphlet that Minnie Parkhurst had finally printed, to raise money for other political prisoners – “my jailbirds,” as Olivereau called them.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation kept an eye on Olivereau, listing her as an “Alleged Radical – Communist Party” in 1921. In Red Scare hyperbole, the FBI agent remarked in his report, “[Olivereau] is alleged to be the head of all Russian propaganda in the United States.”

Louise Olivereau stood in the Seattle spotlight for a very short time. She moved to the city in 1915 and was sent to prison in Colorado in 1917. She returned for only a few weeks in 1920, before moving away for good, eventually living and dying in California. But she matters in the city’s history, because she asked and answered in public the most difficult of civic questions: What does a responsible individual do when she judges her country’s actions to be repugnant, and doesn’t want to be complicit in them?

Louise Olivereau acted on her convictions, gaining a public platform to speak her mind and to eagerly rush to the martyrdom of prison, “like a moth rushes on a flame,” as Anna Louise Strong put it. Her words and actions send a challenge to our political conscience across the decades: When we dissent, what do we do about it?

--

Lorraine McConaghy is the Public Historian Emeritus at the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle. Comments? Suggestions for future entries in this series? Contact the author via editor@crosscut.com.

Images courtesy of Seattle Post-Intelligencer, University of Washington, and the U.S. Library of Congress.

The author is deeply indebted to her friend, the late Sarah Ellen Sharbach, whose master’s thesis at the University of Washington is the best starting point for understanding Louise Olivereau.