A telephone rings, the old variety, the sort that plugs into walls and needs no electricity. The receiver lifts and a voice answers, recognizable as Seattle hip-hop artist Ishmael Butler of Shabazz Palaces.

“Yo,” he says. “Have you ever been swallowed by the light?”

$(document).ready(function(){ if( /Android|webOS|iPhone|iPad|iPod|BlackBerry/i.test(navigator.userAgent) ) { // some code.. }else{ var video = $('#autoplay-video').html(); $('.field--name-field-hero-image').html(video); } })

These are some of the few words spoken in “Vans Syndicate,” director Kahlil Joseph’s 2010 short film for clothing company Vans. If you can call it a skateboard video, it’s perhaps that genre’s most abstract entry. Shot in black and white, it makes the combination of kick-flips and symbols from the I Ching — the ancient Chinese “Book of Changes” — seem somehow natural. In one shot, wind serenely blows through a home’s open door, sunshine splashing across a rug. Skateboarders seem to glide across grass in another.

Butler’s is also the first voice you’ll hear entering Young Blood, an exhibition of Joseph’s work and that of his late brother Noah Davis, now in its final weekend at the Frye Museum. A Seattle-born filmmaker capable of both creating masterpieces and breaking into the mainstream —see his recent work on Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” visual album — Joseph deserves attention from every true fan of visual art.

The moment I saw “Vans Syndicate” six years ago, time seemed to alter briefly. By the time the soundtrack from pioneering electronic producer Flying Lotus drops, there was no question the director was tuned to a new frequency. It was the second collaboration between the musician and filmmaker, “Until the Quiet Comes,” that provided his first true mind-melting moment, as well as wider attention.

An otherworldly meditation on the violence and early death faced by many black males in the United States, the video provides a glimpse of what our society might look like to a higher form of consciousness. It won Special Jury Prize in the 2013 Sundance Film Festival’s short film category, and has racked up nearly 3 million views on YouTube.

Writing on the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s website, visual artist and scholar Duane Deterville argues that the video channels aspects of deep African mysticism like a form of séance, calling it an “Afriscape ghost dance.”

“The consensus of opinion amongst my peer group is that Joseph’s short film is pure genius,” Deterville wrote. “But beyond that, it seems to have touched and strummed a chord of emotion in some of us that is beyond the words that we normally use to describe a film.”

There is a form of spirituality on display in Joseph’s best work, ambiguous but clear. Case in point: the main video on display at the Frye’s exhibition, “Wildcat.” Returning to the monochrome of his Vans video, the film documents the all-black rodeo in Grayson, Oklahoma, elevating it to a “state of mind” full of cowboys and angels, in Joseph’s words.

Joseph has always “paid attention to video art and installations; I know what their potential is, and can be, to communicate ideas and emotion.” So he likely took special care in working with curator Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes to present “Wildcat” at the Frye, deconstructing its scenes and broadcasting them onto a suspended triangle of three semi-opaque screens. The swirl of images — men on horses, rolling thunderstorms, young women in formal dresses — blend together and present the rodeo as a sort of dream, a feeling amplified by the dissonant, harp-heavy soundtrack provided by (you guessed it) Flying Lotus.

But just as notable as the screens’ arrangement is what’s beneath them: a large triangle of dirt. A nearby sign informs patrons this is dirt from the actual rodeo, small bits of trash and all. Beyond its aesthetics, one senses it’s there as a talisman, a transposed bit of holy ground from the countryside, now on the floor of a city museum.

If Joseph’s work seems to tap into an old, non-Western sense of the spiritual, that’s no mistake — after all, his film with Brazilian musician Seu Jorge was titled “Oshun and the Dream,” a reference to a feminine manifestation of God found in some West African traditions, who has also been incorporated into religious practices in Brazil and Cuba.

In his frequent use of water to represent the divide between this world and whatever lies beyond it, Joseph is utilizing symbolism that’s millennia old. Beside its presence in “Until the Quiet Comes”, it can also be found in his video for Beyoncé, showing the singer suspended in water as a post-suicide ghost, or a subconscious version of herself. Another frequently employed image is modern people on horses — found in “Wildcat,” as well as “M.A.A.D.” a short film depicting the L.A.-area city of Compton, shot for rapper Kendrick Lamar — another conscious effort to intertwine the old ways and the new.

Beside the masterful work on display, perhaps the most compelling reason to visit Young Blood is that the exhibit itself represents an once-in-a-lifetime, deeply personal statement. Housed in a museum directly next door to his former high school, it is not only a presentation, but an attempt by Johnson to honor his late brother, and to keep his legacy alive.

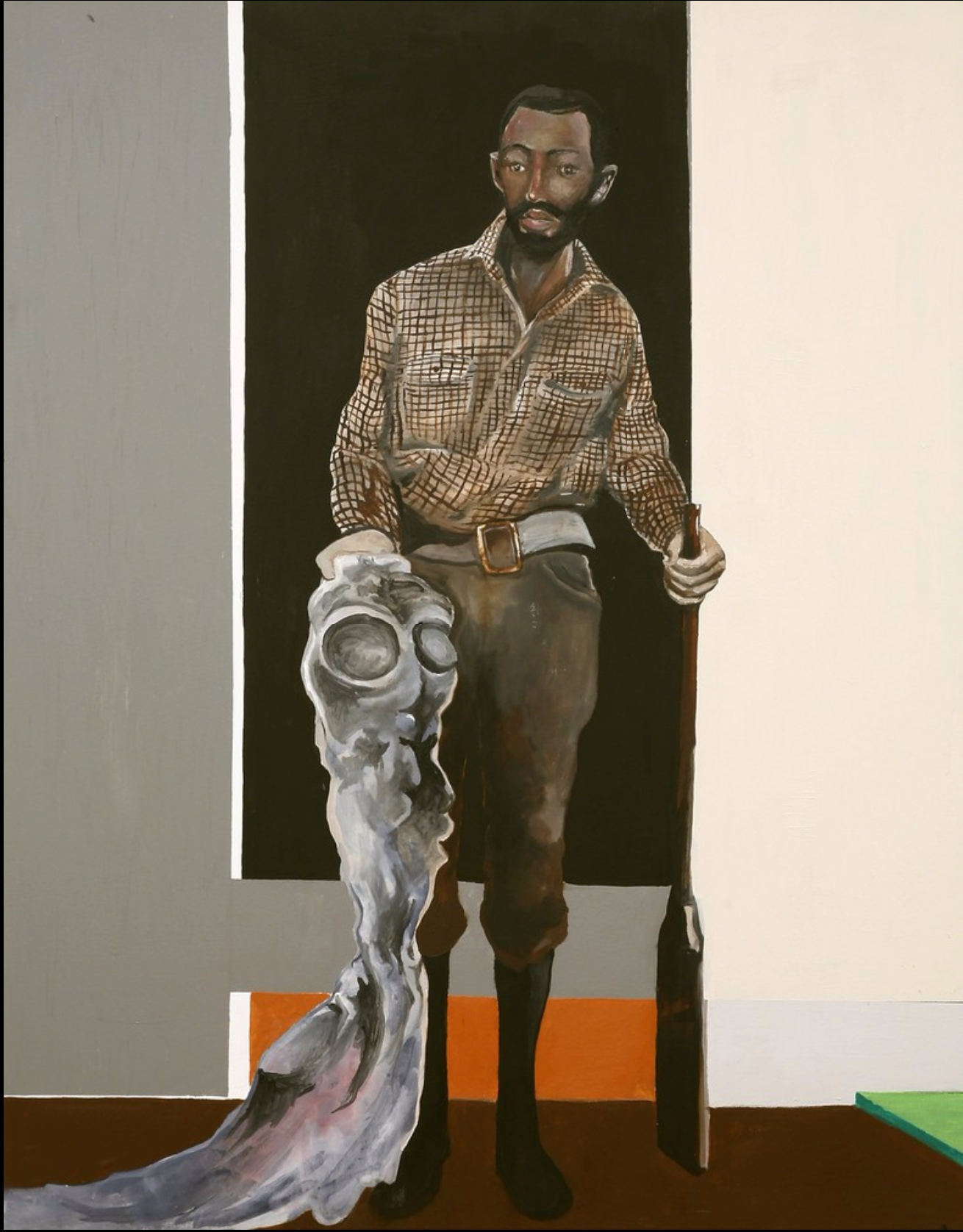

Last summer, painter Noah Davis passed away following a battle with cancer, at the age of 32. Already a massively talented artist in his own right, this exhibit gathers work from throughout his career, as well as paintings from the Underground Museum, which Davis founded to expose low-income residents of Los Angeles to high-level art. The exhibit’s expert curator, Alley-Barnes, had a friendship with Davis stretching back to preschool.

When one encounters the small, darkened room featuring video footage of Davis, shot partially by Joseph and never seen outside of his family before now, the point is driven home — Young Blood represents an artist returning home to bare his soul and his grief, and to remember his brother in the place they grew up together.

It’s been said that genius is the return of one’s rejected thoughts with an alienated majesty. But do dreams count? What about old visions of our place in the world, and how we leave it? How about all the things that our senses perceive, but our minds cannot process?

These are the deep veins being tapped by Joseph, an avant-garde artist operating at the height of his powers, whose future seems like it could contain everything from major museum exhibitions to Oscars. But how to summarize what’s on display right now at the Frye, and in the work of both brothers?

Perhaps Ishmael Butler put it best in that 2010 Vans video, whispering: “Pure being. Pure light.”

All images from the films of Kahlil Joseph

Design and animations by the author