Friday April 5, 2019, represents the 25th anniversary of Kurt’s Cobain’s suicide. The death of Nirvana’s frontman remains one of the darkest moments in pop history.

His status as an icon in music appears cemented, and nearly any poll of music greats has him near the top of the list. Nirvana was enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014, its first year of eligibility, and the band remains a staple of radio year after year.

But Cobain’s status is something altogether different in Seattle, a city that shaped him, and that in ways he shaped. Grunge and the Seattle music scene that Nirvana spearheaded changed how Seattle was viewed outside of the city, but they also changed how Seattle viewed itself. Music gave Seattle an identity beyond Microsoft and Boeing and instead of being a place that made planes and software, Seattle became ground zero for youth culture and alternative music. When Nirvana’s Nevermind hit the top of the Billboard charts in January 1992, that feat alone represented the start of a different Seattle, a city that created culture rather than followed trends. Having Microsoft gave Seattle economic clout, but it was only in the post-Grunge era that Seattle had cultural swagger.

There have been other Seattle music stars, but few have been as tied to Seattle in the mind of the popular zeitgeist as Kurt Cobain. Jimi Hendrix was born here, but his music is rarely described as “the Seattle Sound,” and Hendrix had to venture to London to find fame. Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden and a thousand other bands all played a part in our musical revolution, but in the mind of the rest of the world, and on the charts, everyone followed Nirvana.

Almost all the “think” pieces or retrospective news stories looking back on Cobain’s influence will contain the description “Seattle’s Kurt Cobain.” That’s the way the wire service pieces always read, the way the initial obits read. The linkage seems permanent for the city and for Cobain, though he only officially had a home address in Seattle for 13 months, and much of that time was on the road touring.

He spent his first 19 years in Aberdeen and only moved to a Seattle home address in March 1993. He had lived in hotels in the city for several months and in 1992 had purchased a getaway home in Carnation, but rarely spent time there. His first Seattle address was, of all places, a house in Lake City rented for nine months. He and Courtney Love then bought a house in the Denny Blaine neighborhood in January 1994 for $1.3 million. Cobain died there, committing suicide in a greenhouse above a detached garage, unpacked moving boxes strewn throughout their home. The park next to his home on Lake Washington Boulevard is as close as it comes to a Seattle memorial, and that’s where fans usually gather on anniversaries. They will do so again today.

Another irony is that even for Kurt Cobain, Seattle was too expensive a city, prefame. He couldn’t afford $137.50 rent for an Olympia apartment he shared with a girlfriend, and when they broke up he truly struggled. He worked as a part-time janitor and had other odd jobs while doing his music. Eventually, Nirvana was signed to a major label record deal and he went to Los Angeles in the spring of 1991 to record Nevermind. When he returned home to Olympia, he found all his belongings on the curb, as he’d been evicted. After recording an album that would go on to sell 25 million copies — which no one knew would happen at the time — Cobain then slept the next few days in his car.

Just driving to Seattle from Olympia was often a financial hurdle Cobain couldn’t manage. I read through all of Cobain’s journals and diaries, many of which are unpublished, and Seattle is mentioned often, long before he moved to the city. He wrote numerous bio sheets for Nirvana, and in almost all, he tried to connect himself to Seattle (usually by claiming the band was “from the outskirts of Seattle”). He also complained about how pricey Seattle was, and how much it cost to drive to Seattle from Olympia. In one unmailed letter to Dale Crover of the Melvins, Cobain wrote he had planned to drive to Seattle for a Melvins show, but in the end, he just couldn’t afford the gas as he had found only one other person to split costs with. “It would be too fucking expensive” with only one passenger, he wrote. Back in those days, gasoline was less than a dollar a gallon.

Finally, Nirvana began to get some attention in Seattle clubs and, at first, the band made gas money and then eventually a profit of a few hundred dollars a night. In another unmailed letter, to a friend from high school, Cobain boasted, “We are becoming very well-received in Seattle…. Promoters call us up to see if we want to play, instead of us having to hound people for shows. It’s now just a matter of time for labels to hunt us down, now that we’ve promoted ourselves pretty good by doing small remote tours.” Nirvana was signed to Sub Pop, released a single, then an album, and by 1990 its Seattle club shows were selling out, which is what attracted a major label to them.

Another myth around the “Seattle’s Kurt Cobain” line is that as late as 1990, Nirvana was still not thought of as the biggest band in Seattle, or even on the Sub Pop label (Mudhoney held those reins). It took Nirvana touring college towns and touring Europe for the band to get some traction. Cobain also began to write pop-oriented songs like “Sliver” and “Lithium.”

Nevermind came out in September 1991 but didn’t hit the top of the charts nationally until four months later. It was an immediate hit in Seattle once station KNDD played “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” But it was truly MTV that broke Nirvana wide when the video of that song made the album and Cobain famous.

There is no song more closely associated with Seattle than “Teen Spirit,” but even this song has a tenuous actual connection to the city and much mythology. Cobain wrote the song in Olympia, Nirvana first played it at a rehearsal in Tacoma and Nirvana recorded it at a studio in Van Nuys, California.

Seattle’s claim is that Nirvana debuted “Teen Spirit” here before an audience at the O.K. Hotel club in Pioneer Square on April 17, 1991. For all the legend of the song, you would think the Seattle audience in the building would have demolished the structure with enthusiasm. Instead, the crowd responded more enthusiastically to other better-known songs in the set.

The building that housed the O.K. Hotel still exists, but it long ago stopped hosting shows. Now, like almost everywhere else Nirvana played Seattle, the space is the O.K. Hotel Apartments.

If there is one sign of how much Seattle has changed in the past 25 years, it could come in tracing the places where Nirvana actually played in the city. There were a couple dozen venues that hosted Nirvana on the way up, but just a fraction of them still have music.

Here’s an incomplete list, starting in 1988, with the current use noted:

- The Vogue (building still stands, club is long gone, now a hair salon).

- The Central Tavern (still standing, remodeled).

- Moore Theatre (still standing).

- Squid Row (demolished, condos).

- The Underground (demolished, offices).

- University of Washington HUB Ballroom (still standing, remodeled).

- Annex Theater (demolished, condos).

- C.O.C.A. (demolished, condos).

- Motor Sports Garage (demolished, condos).

- The Off Ramp (still standing).

- O.K. Hotel (still standing, different use).

- Beehive Record Store (still standing, different use).

- Paramount (still standing).

- Seattle Center Coliseum (still standing, being rebuilt).

- The Crocodile (still standing, remodeled).

- King Theater (demolished, condos).

- Pier 48 (still standing, different use).

- And finally, the last place the band played in Seattle, the Mercer Arena (demolished).

One does not have to be a land-use attorney to realize that, 25 years later, this is a very different landscape for music in Seattle. Nirvana never played the Showbox, in part because that venue wasn’t hosting up-and-coming Seattle bands in Nirvana’s early years.

There are only three venues that Nirvana played over the years in Seattle that still have interiors similar to what they did when Nirvana played there: The Moore, the Paramount and the Off Ramp (now El Corazon). The first two are theaters protected with landmark preservation status, while El Corazon, a club that also hosted Pearl Jam’s first show, was recently in the news because that site may be developed.

Nirvana’s show at the Off Ramp attracted five different major labels and essentially it was that performance, and watching the response of the Seattle crowd, that persuaded major label DGC to sign them. Many things made Nirvana and Kurt Cobain an icon, but one small piece of that history was made in that dingy club on Eastlake, which at the moment still exists.

Death anniversaries are particularly hard to understand or to participate in. I spent years researching Cobain’s life, but there is much that still feels like a mystery, perhaps because suicide and addiction themselves are unknowable demons. There were 30,000 suicides in the U.S. the year Kurt died; in 2017 there were roughly 45,000, including two people I knew, one of whom happened to be Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, who often brought up Cobain when we talked. Suicide takes the lives of more Americans now than traffic fatalities.

And don’t get me started on opioids because I think about that and Cobain every time I drive down Aurora Avenue, a part of the city still filled with sleazy hotels where Cobain often stayed on drug binges. The word epidemic is finally used to talk about the opioid crisis, but to those in Seattle music, this is old news. Starting with Andrew Wood in 1990, there has been a long list of famous and soon-to-be-famous deaths.

The most haunting spot on Aurora is at a small locale near Shoreline that was once a gun store. It was where 25 years and three days ago, Cobain bought a box of shotguns shells for a gun he had purchased the previous week on Lake City Way. I think the most pain in my heart goes to thinking of that moment, trying to understand what is not possible to truly understand, and trying to come to terms with the loss that followed.

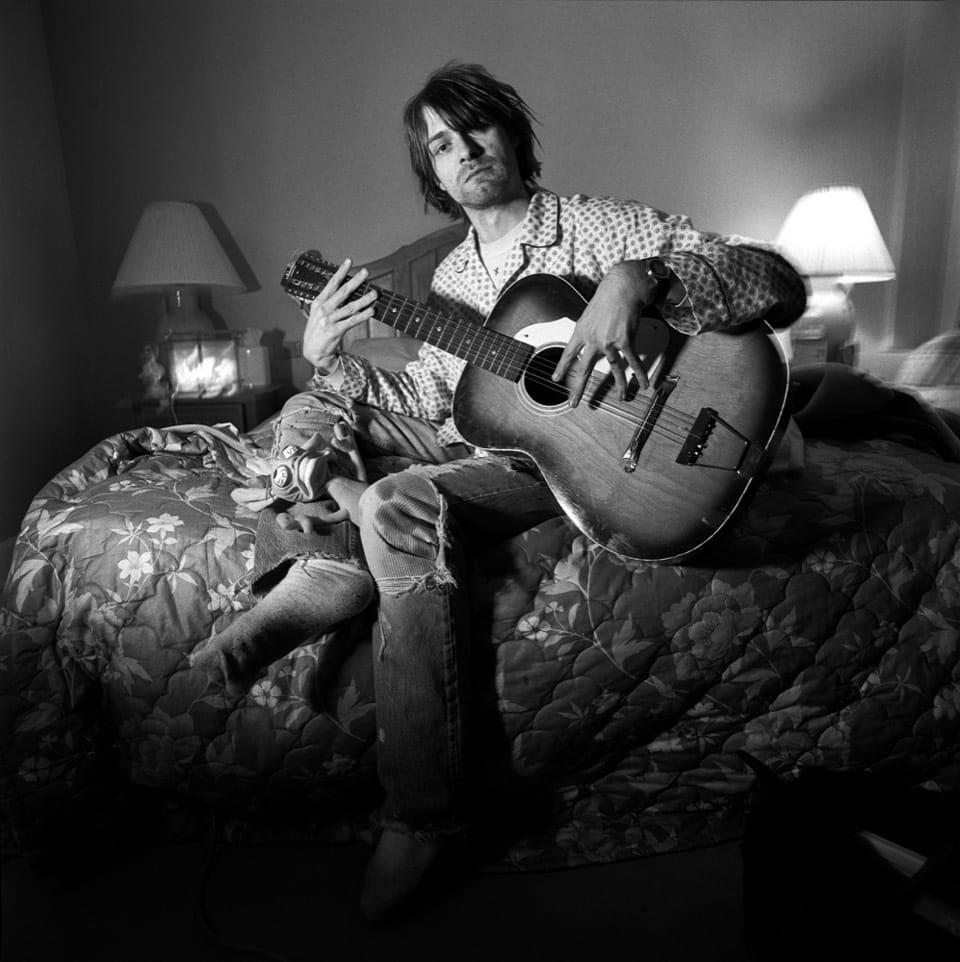

Fans don’t gather there, but instead, they head to an entirely different landscape of vast wealth, on Lake Washington Boulevard and to Viretta Park, next to the Cobain house. The home is a private residence, with high fencing installed after Courtney Love sold it to people with Microsoft money. The greenhouse where Cobain died was torn down years ago. Fans leave messages, flowers and notes on the park benches. Usually, on anniversaries, there are crowds and tears and someone singing a Nirvana song on an acoustic guitar.

Kurt Cobain lived in Seattle for a remarkably short time, but 25 years later, his music still wafts, sometimes just in my memory, sometimes out of demolished buildings or from the windows of fancy condo developments. Back in history, rock ’n’ roll was once alive and vital and so was he.