The couple both hailed from Texas, so they had a certain air of Southern formality about them. Always fashionable, she had on a nice dress and he, as was his custom, a coat and tie. Always the gentleman, he likely held open the doors for her, and pulled out her chair at their table.

It was a big night for him, so he was in the mood to splurge. He chose the Hotel Sorrento on First Hill, one of the grandest spots in Seattle in the early 1950s. It was as magical a place as they could imagine, she later recalled.

At his urging, she ordered the lobster thermidor. She was in her late 20s, and it was the first time she’d eaten lobster of any kind.

“It was delicious,” Mildred (Long) McHenry said decades later, lightly smacking her lips at the memory. The Sorrento would become one of their special places.

Already one of the first two Black engineers hired by Boeing, her companion, Gordon A. McHenry, was celebrating another first — becoming the first Black engineer promoted by Boeing into management. Gordon was Mildred’s future husband, but that night they were just friends. They married in 1955 and stayed wedded for 46 years, until he died in 2001.

His career timing had been perfect. Much earlier, and the two would not likely have been able to salute his accomplishment in a place like the Sorrento. During her early years in Seattle, Mildred remembered, the tables at white-owned restaurants routinely were adorned with “reserved” cards.

“There would be lots of tables with nobody sitting at them,” she said. “It was just their way of keeping Black people out.”

Mildred McHenry witnessed a lot of Seattle’s regrettable racial history during almost 95 years of a life that ended in December, on Friday the 13th, an unlucky day for so many of us. The timing of her departure, during the holidays, added to the devastation of her loss. Yet in a way it also was apt because she left behind a gift — that of forgotten history.

When she moved to Seattle in 1944, Mildred settled in the Central Area. It was not yet Seattle’s “historically Black neighborhood,” however. It was an almost exclusively white area. At her passing, Mildred McHenry had been one of the few remaining witnesses of a neighborhood that had gone from white to Black and back to white — a story of segregation, desegregation and gentrification.

I was fortunate to have recorded a lot of her history. A woman I called Second Mom for more than 50 years, Mildred McHenry had occupied the highest ranks of the village it took to raise me. When I sat with her during several of her final Sundays, I asked for details of her life and permission to write about them, and she agreed.

Once in a while, she’d pause and say, “I’d better watch what I’m saying because you’re writing it all down in your little book.”

“Don’t you trust me?” I asked, only half serious.

“With all my heart,” she’d say, then resume recounting her young adulthood in Seattle, matter-of-factly and with little judgment.

I make this latter point because the segregation and subsequent gentrification of Seattle’s Central Area was, to her, as the great hoops philosopher Gary Payton might put it, just something that happened.

“We never let race be a point of conversation in the house,” Mildred said of raising her sons, Gordon Jr. and Eric. “There was no use for it. We taught our sons to get an education and be prepared for the outside world.”

When then-Mildred Long moved here, Seattle wasn’t exactly a beacon of hope for Black folks like her. The point of her northern migration was more about whom she was following, and what they’d left behind.

Her older sister, Helen, whom she idolized, arrived first, for a job at Bethlehem Steel. Mildred left Terrell, Texas, with the vague notion, as she said, “that the opportunities were much better for Blacks in Seattle.”

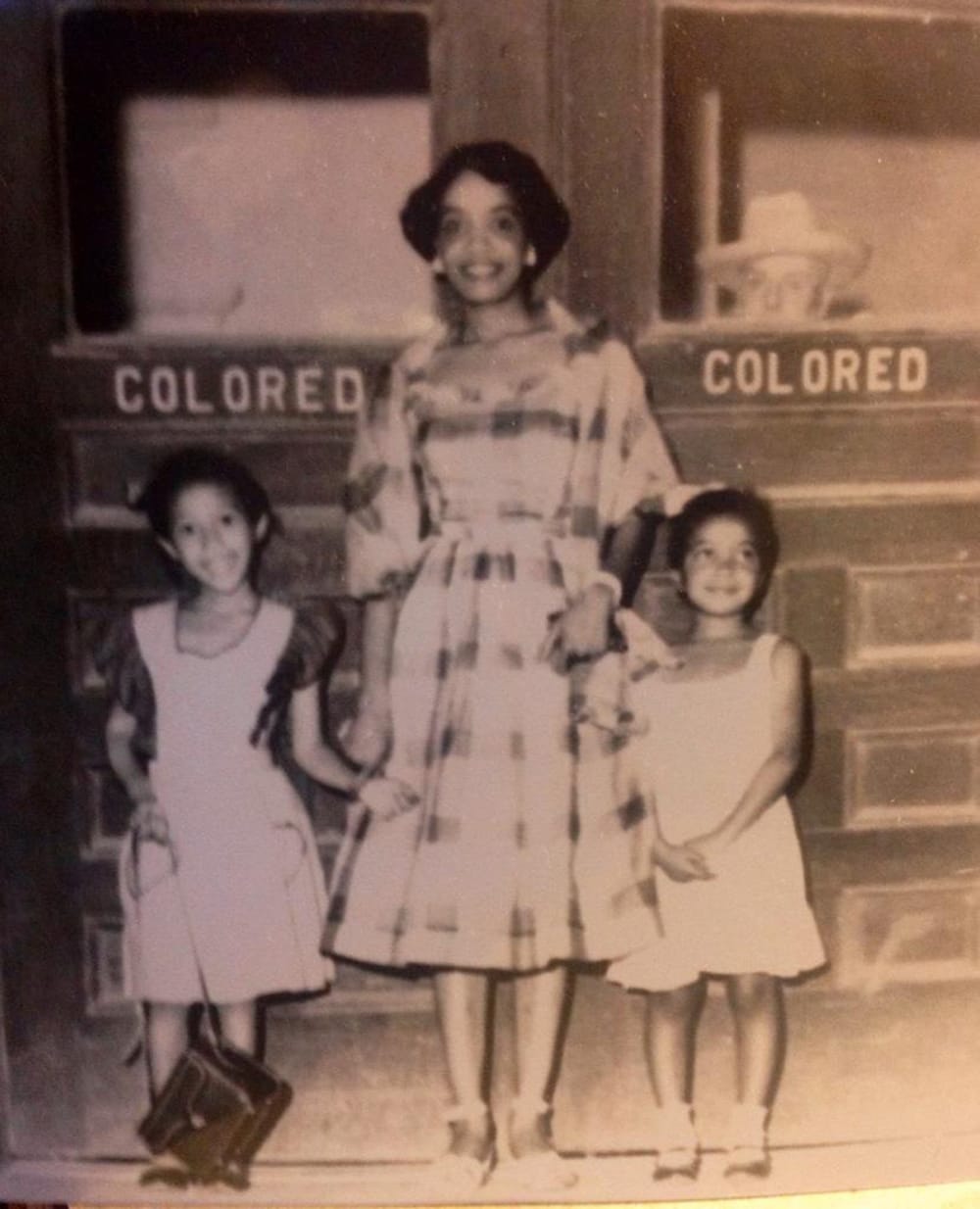

The bar wasn’t exactly high. Seattle had a minuscule Black population back then. But it was wartime and the region’s strong military presence was attracting a more diverse population. That all held much more promise than Mildred’s hometown in East Texas. Terrell was part of the still-segregated South, with a past as a sundown town, excluding nonwhites with a vile brew of discriminatory laws, intimidation and violence.

Her parents, Nadie and J.W. Long, had encouraged their children to find a way out of Terrell. “Get educated,” they’d say, “then get out of town.” They taught their offspring well. Mildred’s youngest sister, Nora, was a well-regarded career educator, mostly in Seattle. Mildred attended Burnett High School, a segregated school that her father had organized. J.W. Long’s name continues to adorn the elementary school in Terrell today. In the custom of Black men of that era, he went by initials — J.W. — to counter the disrespect of being addressed by whites by their first names, like children. As was also custom, his children never knew what J.W. stood for.

Mildred landed in Seattle’s Central Area because Helen lived there. They shared an apartment until Mildred landed a unit in a duplex on 24th Avenue. This was just a block from the East Madison YMCA, which, unlike a lot of early Central Area institutions, still exists today. By chance, the duplex also was mere blocks from Mount Zion Baptist Church, which would become the epicenter of her life. In those days, the area’s growing Black population went either to Mount Zion or First African Methodist Episcopal over on 14th.

By then, Mildred was working at the Seattle Water Department and taking night business courses at the University of Washington. The UW provided the nucleus of her social group. Occasionally, they’d venture out to the Black and Tan on 12th and Jackson, or other Black clubs, but their conviviality mostly was confined to the area bordered by Mount Zion and the YMCA, where they met on Sunday afternoons to play cards — Bohnanza and Whist — for a penny a point.

“The guys pitched in for booze,” Mildred said, “and the girls brought the food.”

Over time, more of their energy went into Mount Zion. The Rev. F. Benjamin Davis was charismatic and forward thinking, and the congregation doubled under him. Mildred worked on one of his committees targeting the mechanisms that fed the city’s segregation. The kind of multifamily structures where Mildred lived were being replaced in other areas by single-family units, the presumption being that nonwhites could not afford them. The organization that grew around ending desegregation eventually helped the legendary Sam Smith get elected in 1957 to the state Legislature, then in 1967 as the first Black member of the Seattle City Council.

But Mildred wasn’t there for the politics.

“I was too young for that,” she said. “I liked to have fun.”

Her life took a turn to the serious when Helen died suddenly at just 30 years old. The event rocked Mildred’s world; at the same time it brought her future into focus. A quiet, serious and razor-sharp young man had been part of Mildred’s “running around” group, but she hadn’t taken notice. “He didn’t speak until he had something to say,” Mildred said.

In the aftermath of her sister’s death, “the rest of the group left,” Mildred said, “and Gordon was still there for me.”

In 1957, two years after their marriage, they were ready to buy a house — a tall order for a Black couple. It had “gotten around” at Mount Zion that a real estate agent was willing to show homes on Beacon Hill. The rub: For Black folks, the showings were only at night, when white sellers could conceal their intentions from racially intolerant neighbors.

Though they found a place where they raised their sons, I wondered if the McHenrys harbored any anger at the constant race-related barriers they had to endure. Mildred placed a hand on my arm and said my name to ensure I was fully attentive. I was.

“That’s just the way things were,” she told me in her lightly Southern lilt. “You’d get mad, but you couldn’t do anything about it. You were locked into a way of being. I expected some of those things because I grew up in the South. Seattle was so much better than there. Taking those things on — that’s for your generation and my grandchildren’s.”

Seattle provided enough for Mildred to mold a family that has left a definite mark on her adopted city. In addition to breaking ground at Boeing, her late husband was an active, behind-the-scenes civic leader. Her oldest son, Gordon Jr., followed in his father’s footsteps, with a slightly higher profile, most recently taking the helm at United Way of King County.

Mildred (Long) McHenry — Millie to some, “Boots” to many because of a pair of boots she adored and wore to disintegration as a young girl, Aunt Bootsy to her nieces and nephews and grandnieces and grandnephews — had big personality, big faith and even bigger heart. She said many times that she was ready to go. “I’ve lived and seen enough,” she told me. At the end of one session, we went through a list of friends and families, trying to identify another survivor of what might have been a forgotten era in Seattle’s racial history.

“I’m the last one,” she said.

She chuckled lightly — as usual, more hee, hee than ha, ha. “Just think of what this old lady has seen,” she continued. “My little city has really grown. It has really changed.”

Part of that change, that inexorable march of time, is a world without one of the baddest women I’ve ever known. At least, for now, we still have the Hotel Sorrento, still glorious and on a beeline down Madison Street from the YMCA and Mount Zion. And in our hearts, we’ll always have the scene of a young Black couple in the early stages of an adventure so full of challenge, uncertainty and of course love.