The image of NASA’s first Mercury astronauts — the guys with the right stuff — is indelible. They ushered in America’s age of space flight, and the group included the country’s first man to orbit the earth.

But they were preceded by an earlier generation who also had the right stuff: aviators who launched a flight that began and ended on an obscure airfield in Seattle. They achieved a dream: the world’s first around-the-world flight.

It’s too bad so few remember.

They were called the “Magellans of the Sky.” It’s safe to say that a new era of aviation took off after World War I. A scramble was on to be the first to fly around the world. Many nations were trying but failed. Airplanes were still a bit rustic, built partly of wood, canvas and cable and having open-air cockpits.

Ever since Ferdinand Magellan’s crew completed the first circumnavigation of the world in 1522, a nation’s circling of the globe was an expression of power, prestige and prowess. To succeed with new technology was to assert leadership in the world today and in the future.

So in the 1920s, the U.S. military decided to seize the moment. Using its ability to plan logistics on a global scale, it mapped out a venture for four “World Cruiser” biplanes built to specifications by Donald Douglas’ aircraft company in California. The light but hardy two-seater crafts would each carry a pilot and a mechanic with minimal gear — only two pairs of underwear for a six-month trip! Talk about going commando.

Leslie Arnold and Lowell Smith in front of the Chicago World Cruiser. (National Archives)

The planes could land with wheels on solid ground or switch to wooden floats for water landings. Eight Army fliers were hand-picked. Traveling light, they carried no radios, no parachutes and no life preservers. They were expected to circle the globe by hopscotching in four- to eight-hour stints, stopping in more than 20 countries, some of which had not yet seen an airplane.

Supporting them would be a network of U.S. Navy, Coast Guard and private vessels that could refuel and provide support. On April 6, 1924, the four-plane World Flight armada — biplanes named Seattle, Chicago, New Orleans, and Boston — took off from the shores of Sand Point, now Magnuson Park, in north Seattle.

They headed north to British Columbia and Alaska, then along the Aleutians across the north Pacific to Asia. Turning south to Japan and China, they would then head toward India, Pakistan, Iraq, Turkey, across Europe to Iceland, Greenland and North America.

Despite logistical support, the fliers would be relying on their experience, using paper charts and visual navigation. They were exposed to the elements: blizzards in Alaska, dense fog, rough seas, parboiling heat in Southeast Asia. If they crashed, they would be on their own, as they would soon find out.

Only weeks into their journey, the squadron leader’s plane, the Seattle, piloted by Major Frederick Martin, crashed into a fogbound mountainside on the Alaskan Panhandle. Martin and his mechanic burned the wrecked plane to keep warm and spent 10 days in the wilds trying to find rescue. They did, but their role in the epic journey was over and underscored the hazards ahead.

Their crash was why the Army Air Service sent four planes. On the first circumnavigation of the world, Magellan started with five ships and 243 men, but only one vessel and 56 sailors made it back—without captain Magellan, who had been killed in the Philippines.

So three aircraft and six crew continued.

In addition to proving that American aircraft could make the epic journey, the fliers also acted as ambassadors for the U.S. and the military. They were celebrated at nearly every official stop. Banquets and speeches tired the weary pilots on each leg, but diplomacy in borrowed suits and uniforms was part of the job.

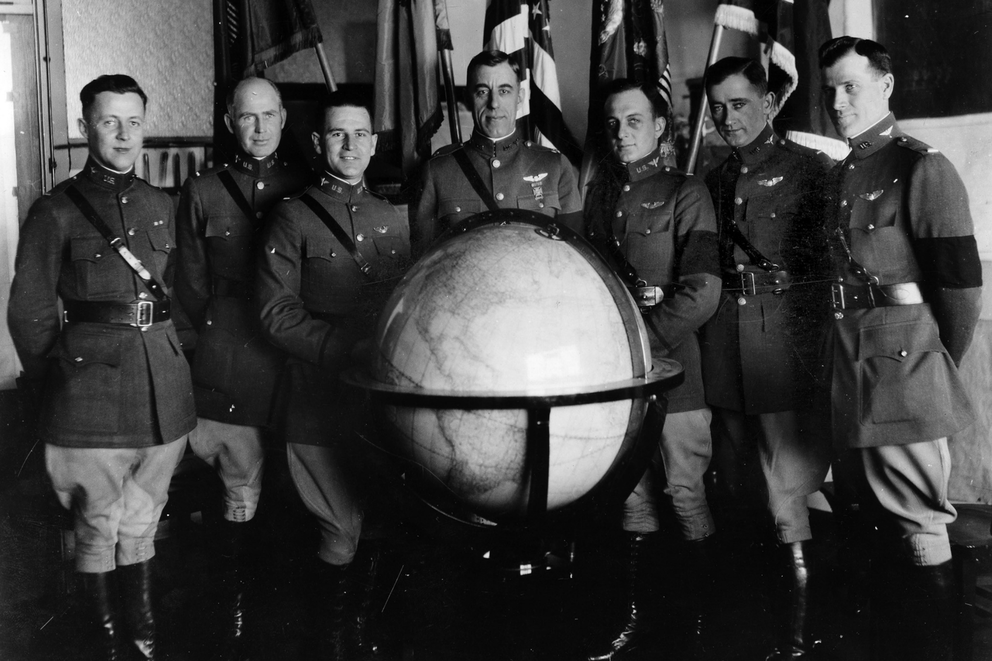

A group photo of the first men to fly around the world. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army)

Champagne functions were punctuated by other, real crises. The new lead plane, the Chicago, for example, had to land on a remote, crocodile-infested lagoon in Vietnam due to an overheated engine. A new engine had to be brought from some 500 hundred miles away by a Navy destroyer and then lugged through the jungle before it could be installed. Meanwhile, a crewman came down with dysentery.

There were often perils in simply arriving at a destination — crowds of people might paddle or swim out to the planes and press in or climb on the machines, threatening to sink or overturn them. Crowd control was often done through hand gestures, or, in at least one instance, scaring folks off by firing a pistol. The wonder of flying machines inspired awe but, sometimes, too much curiosity.

Another plane, the Boston, lasted until Iceland but was ditched and sank in the north Atlantic, though the crew was saved. When the remaining four fliers in the two surviving planes arrived in Labrador at a place called Icy Tickle, they could smell home. In Washington, D.C., they were greeted by President Calvin Coolidge, who waited for them in the rain and even cracked a rare smile. They took a looping tour of the U.S. before flying up the West Coast to land at the finish line in Seattle, where they were greeted by 50,000 people.

This story has been corrected: The plane that landed in a Vietnam lagoon was the Chicago, not the New Orleans.

A World Flyer landing on Lake Washington. (National Archives)