Extreme weather events are well-known in the Pacific Northwest: floods, landslides, massive snowfalls, wildfires, even the occasional wandering cyclone. Remember the Columbus Day storm of ’62?

But in the winter of 1910, a double-whammy proved deadly — back-to-back avalanches that set records for death in the United States and Canada. What caused this twin catastrophe, and why did it kill so many?

Today we hear about atmospheric rivers — vast streams of water vapor in the sky formed by warm temperatures over the Pacific. Depending on their strength and number, they can pound the West Coast. Extreme snow and rain can result. The ones we know form near Hawaii and are called the Pineapple Express. Just one of these can carry more water than the outflow at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

In late February 1910, deep snow was piling up on the western slopes of the Cascades — the mountain barrier that can stop a Pineapple Express and allow it to dump its moisture. This time it stopped a different type of express: trains of the Great Northern railroad where they emerged from the east side of the mountains to the west near Stevens Pass at a railroad town called Wellington.

The Seattle Express from Spokane and a Fast Mail express became stuck there. The track ahead was buried after days of heavy snow, so heavy that even the massive rotary snowplows deployed to clear the railroad tracks were stuck too.

The two trains were held up for nearly a week in an exposed position: beneath the steep slope of a snow-laden mountainside. The Seattle Express passengers were cold, food was running out, and they worried about an avalanche sweeping down on them.

Wellington, Wash., a railroad company town near Stevens Pass. (Washington State Historical Society)

On Feb. 28, the heavy snow turned to rain which increased anxiety. That night, an unusual thunderstorm shook the Pullman car windows and lit the sky with lightning. The winds picked up, and at 1:42 a.m. on March 1, the mountain let loose a blanket of what is called “Cascade concrete.” A slab avalanche of wet, heavy snow rushed down the mountainside and slammed into the two stalled trains. It pushed them — and other locomotives and plows — into a deep ravine and the stream below. One witness described the wrecked train cars as looking like “an elephant had stepped on a cigar box.”

Locomotives swept from their tracks by the avalanche lay on their side near Wellington. (Washington State Historical Society)

It was obvious that there would be few survivors, though some folks made it out. The dead included families, children, businessmen, railroad workers, laborers, conductors, engineers, firemen, mail clerks. The telegraph lines were down, so men set out on foot through the snow to find help down the mountain and alert the outside world. Many bodies were mangled, and as the snow began to melt, corpses were found by following rivulets of blood that emerged in the snow.

The last of the dead wasn’t recovered until the following July. The official toll was 96, but the true number is unknown. Some of the dead were never identified. The bodies of victims were wrapped in Great Northern blankets, hoisted up the hillside in sleds, then stacked like cordwood.

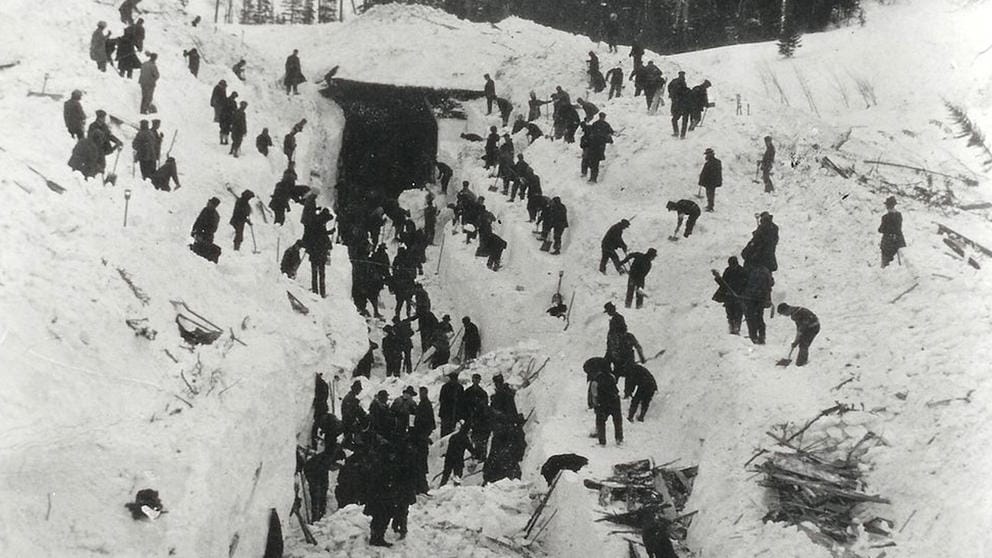

Men recovering bodies from the train wreck near Wellington. (Washington State Historical Society)

Just three days later, disaster struck again at Rogers Pass in the Selkirk mountains of British Columbia near Revelstoke. A slide had blocked the path of a westbound Canadian Pacific train headed for Vancouver. They too were dealing with deep snow caused by successive Pineapple Expresses.

Working through the night to clear the tracks before the passenger train arrived, a work crew of mostly immigrant laborers had nearly finished clearing the tracks. Suddenly, at 11:30 p.m. on March 4, the adjacent mountain let loose its blanket of snow. It fell swiftly and buried the workers. Rescuers and medical personnel were rushed in by rail, but there was only one survivor, a locomotive fireman who had been thrown clear. Sixty-two other men were buried in the snow, some found still standing where they were hit while at work, frozen, it was said, like the victims of Pompeii.

At Rogers Pass, more than half of the victims were Japanese and many remained nameless. The use of immigrants for railroad work was common — the railroads often didn’t even know their names. At Wellington, many of the snow-shovelers were Italian immigrants. They were paid 15 cents an hour. Before the avalanche, some had walked off the job when the railroad bosses refused to up their pay in the miserable conditions. The Great Northern’s railroad baron, James J. Hill, was known as a penny-pincher. Still, the disaster forced him to build a longer railroad tunnel through the Cascades. The town of Wellington was abandoned. Up north, the Canadian Pacific eventually bypassed Rogers Pass and built a new tunnel elsewhere. The avalanche dangers were deemed too great.

Dozens of men attempting to recover victims on Rogers Pass in Canada. (Wikipedia)

In Seattle, an inquest concluded that the Wellington disaster was an “act of God,” though it said the Great Northern could have been more proactive regarding passenger safety. Others pondered nature’s power. An editorial in The Seattle Star opined:

“In after days when the snow piles high on the peaks and the wind comes moaning down the dark chasms, men will tell of Wellington — of those who lived and those who died, of the strong, compressing grip of the snow which crushed Pullman cars and rotary engines to knots of wood and steel and then cast them aside, with the human mites that were in them.”

We mites who live here have learned the hard way that we have to cope with the elements — and their extremes. Pineapple Expresses are no day at the beach.