The landscapes and forests of the Pacific Northwest influence and impact so many who have lived here or traveled through. This place is alive. It speaks. It vibrates. For some, it’s a spiritual experience.

Artists have long sought to capture that experience, from Indigenous carvers of Salish and North Coast peoples to the mid-century modernists of the so-called Northwest Mystics school like Mark Tobey, Morris Graves and Paul Horiuchi.

But one artist captures it like no other. She’s well-known in Canada, but less well-known in the U.S. Her work is unique, original, iconic.

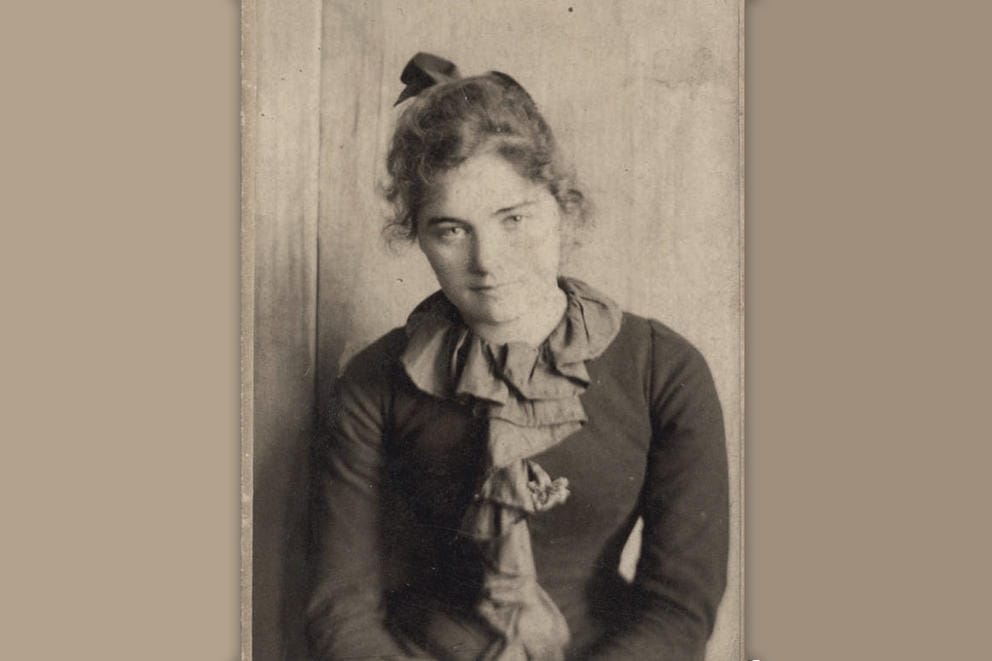

Emily Carr was born and raised in colonial Victoria, B.C. She lived from 1871 to 1945, and spent most of her life there, though she studied art in San Francisco, London and Paris. Her work was heavily influenced by the art she encountered: the poles and figures of First Nations people, the fauvists of Europe, French impressionists and German expressionists.

Carr was eccentric and often worked in solitude. She was a female artist in a male-dominated profession. For a time she supported herself by running a boarding house. She walked around Victoria with a monkey and assorted other pets in a baby carriage — she said her hometown folks were surprised that her years in London had not turned her into a proper English lady.

Emily Carr at 22, during her time in San Francisco at art school (1891/92) (Royal BC Museum)

She had an artistic style that was unique. She became well-known in Canada for her paintings and her writing, which had a very specific focus: the damp forests of Vancouver Island. Her work has been seen through the critical lenses of feminism and romanticism, as well as Canadian nationalism and colonialism, in which her work has been criticized for appropriating Indigenous culture and images.

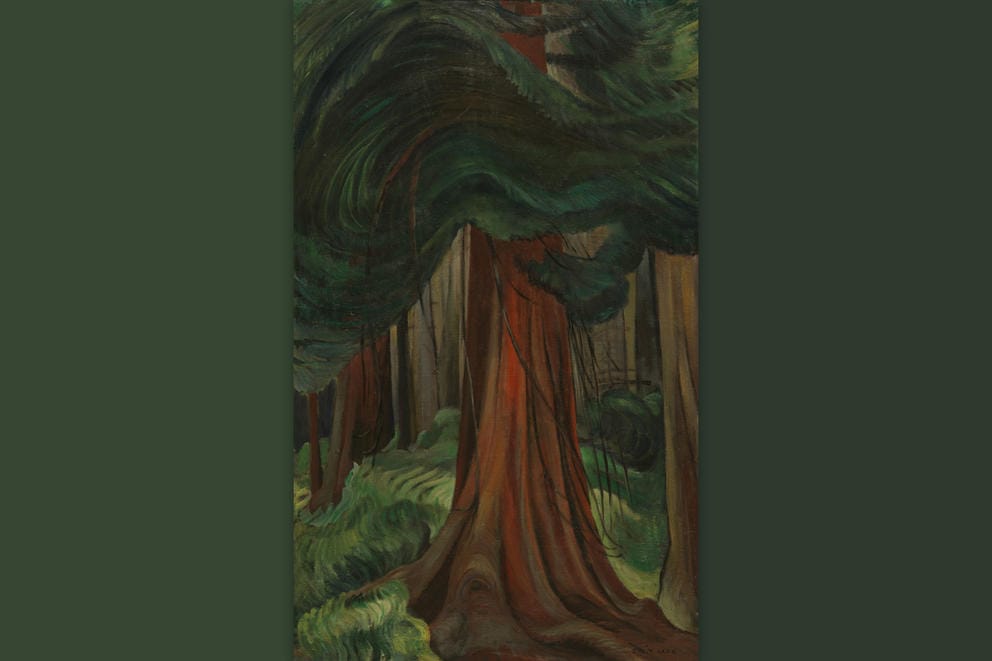

Late in life, from her 50s to 70s, she entered a phase that was especially powerful. No one has captured the Cascadian trees, forests and skies like Emily Carr. As artist Georgia O’Keeffe is to flowers, Carr is to our trees.

Emily Carr, Red Cedar, 1931, oil on canvas (Vancouver Art Gallery)

We now know, as science has shown us, that forests are vast connected communities that communicate and cooperate, that can listen, smell and perhaps even think. They have networks of fibers and fungi, a way of sharing resources like water and sunlight.

But before these discoveries, Carr intuited that web of life and captured it on paper and canvas in her own unique way. She wrote, “I am always asking myself the question, what is it you are struggling for? What is that vital thing the woods contain, possess, that you want? Why do you go back and back to the woods unsatisfied, longing to express something that is there?”

Her red cedars undulate with life like living muscle; her skies and light are complex actors and have vibrancy like a painting by Vincent Van Gogh.

“The liveness in me just loves to feel the liveness in growing things,” she wrote. She felt the connection of things. A biographer, Doris Shadbolt, wrote that Carr had managed to “hang on to a vestige of primal spirit affinity with all the forms of creation.” She said Carr had created a “Pacific mythos.”

Carr wasn’t limited to the idea of “pristine” nature. She painted landscapes scarred by humans — logged, mined, abused. She was not afraid to look at a clear-cut. She could find the beauty and energy where trees and sky met gravel pits and stumps. She could connect where others might only feel sadness. “Mother Earth,” she mused, “will hide it away in her ample brown folds and purify and absorb its good, bringing it back to usefulness.”

Carr takes her viewer into the forest’s dark places too, like moving through multiple drapes into an interior space at once alive, mysterious, inviting, oppressive.

My father worked on a logging-camp survey crew deep in the old growth on the Olympic Peninsula in the 1930s at the time Carr was painting her forest pictures. He described places that were silent, where sound was muffled. When the forest went quiet, he said, you might spot a bundle in the canopy above, likely a traditional Indigenous tree “burial” of a deceased ancestor.

If much of her work captures, as one critic put it, the “trembling luminosity” of the sky, she also painted the intensity of the coastal forest that can seem like a living womb or tomb.

Great art is unique but speaks to a larger truth — often feelings that are hard to put into words or images.

Before science uncovered secrets of living forests, Emily Carr’s paintings captured their essence, and their knowing.

For more on this story, listen to the Mossback podcast. You can find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon or wherever you get your podcasts.