In the late 1890s and early 1900s Seattle was an open town. This meant that prostitution, dance halls, saloons, gambling and opium proliferated, especially in the city's so-called Tenderloin district, below Yesler Way. Customers proliferated as well, thanks to the discovery of gold in the Klondike.

Tens of thousands of people flooded into the city to take part in the last great Gold Rush in North America. While it appealed to a younger generation who had missed previous rushes, it also attracted old-timers who wandered from boomtown to boomtown looking for a score.

The biggest name Seattle’s Tenderloin drew in that time? The legendary Wyatt Earp.

The former lawman, gambler and gunfighter was well-known. Even back then, the OK Corral was shorthand for a famous street fight in the silver mining town of Tombstone, Arizona, where Earp, his brothers and Doc Holliday gunned down some bad guys in 1881.

The O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, after a fire in 1882. (Wikimedia Commons)

But Earp’s story is more complicated than a single shootout. Many considered the Earps bad guys and viewed the confrontation in Tombstone as more of a gang war than a case of justice being served. Earp was also regarded as a sporting man — a gambler and saloon owner as well as a lawman. He was best known in the late 1890s for having refereed a heavyweight boxing match — a fight he was accused of throwing by declaring the clear loser the winner. It tarnished his reputation.

Wyatt seemed addicted to the thrills of frontier towns, and the Klondike offered him a familiar and high-stakes opportunity. With his common-law wife Josephine, he headed to Alaska and the Yukon in 1897.

As Earp well knew, the real money wasn’t panning for gold — it was in “mining the miners.” He and a partner opened a saloon and gambling parlor named The Dexter in Nome, Alaska, and it proved to be, well, a gold mine as miners spent, drank and gambled away their finds.

Earp met a Seattle sporting man named Thomas Urquhart, and they hatched the idea of opening a gambling parlor in Seattle too. If it could work in Nome, why not in the populous Gold Rush hub on Puget Sound?

In November 1899, it was announced that Earp was setting up a new “gambling house,” the Union Club, on Second Avenue between Yesler and Washington Street, right in the heart of the vice district. Gambling parlors were operating roulette wheels, slot machines, faro banks, blackjack tables, even so-called “Chinese” lotteries.

“Earp has lived on the frontier all his life,” the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported, “and is said to have killed several men during his career. Personally, he is … good-natured and does not talk much.”

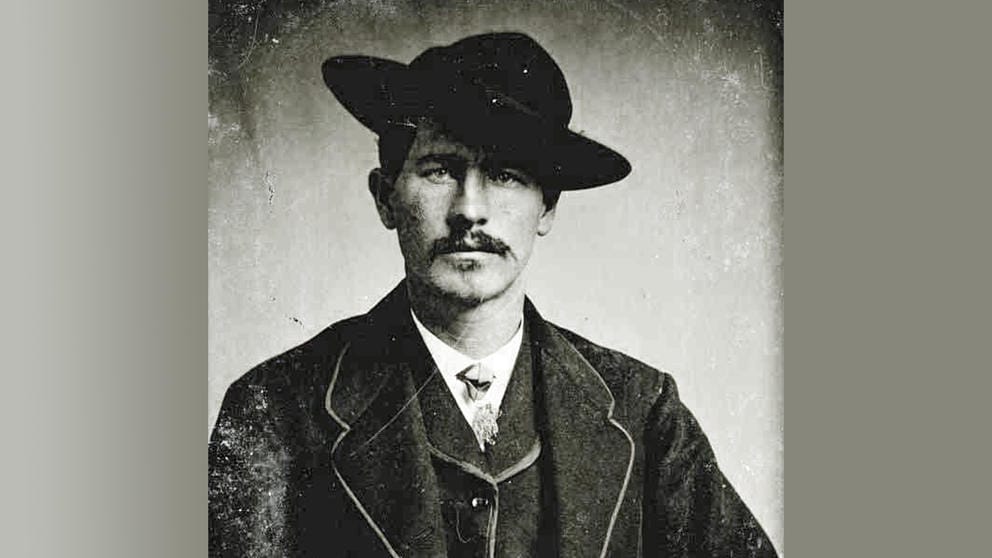

Wyatt Earp in the mid-1870s. (Wikimedia Commons)

Good-natured or not, the lanky, mustachioed lawman was not welcomed by all. “The clique of boss gamblers in Seattle is badly disgruntled over the threatened appearance of an ex-Arizona sheriff in the role of competitor,” reported The Seattle Star.

The estimated profit his parlor could make right off the bat was $15,000 to $20,000 per month after expenses — that would be more than $600,000 a month today. To the existing local gambling clique, that competition would be money out of their pockets.

And those expenses? They would include graft and protection payments. Though Seattle was considered an open town, gambling was illegal, as was prostitution and saloons and show-box theaters that allowed male and female patrons to mix. The vice ecosystem flourished because payments to the police, politicians and judges helped ensure they could operate — if they paid up. And for the city? Fines paid by gamblers were effectively a kind of tax on Gold Rush prosperity.

Earp landed amid a turf war among gambling interests and a periodic police crackdown that shut parlors. The crackdowns helped extort more money from the operators while seeming to defend public morals.

John Considine, later a theatre and vaudeville impresario, was the gambling big cheese when Earp arrived. Earp refused to “pay to play.”

“The new man refuses to put up,” proclaimed the Star. “You fellows are paying enough,” Earp told the Considine-led gambling combine, “why should I add any money?”

The Union Club opened in late November ’99, but was shut down only a few months later, its gear confiscated by the police. The only gunplay on Earp’s part was early on when he knocked a man on the head with his revolver during an argument in a bar. In contrast, a little more than a year after Earp left town, Considine shot and killed Seattle’s former police chief William Meredith in a shootout near the old Union Club. The Tenderloin was a Tombstone all its own.

Seattle may have just been too corrupt for Earp, or perhaps the risk was just too much. He quickly folded his hand and quietly went back to Nome in the spring of 1900 where his Dexter saloon was a money machine. It’s said when he and Josephine left Nome for good in 1901, they had made the equivalent of $2 million. Reports are they gambled most of it away.

Earp eventually settled in Los Angeles and hung out in the burgeoning movie colony there. He died in 1929, but shortly after, Hollywood films and TV made him an even bigger Western legend. The OK Corral saga grew larger than life, more fiction than fact.

Oddly, the story of Wyatt Earp getting run out of Seattle has yet to be made into a major motion picture.

For more on this story, listen to the Mossback podcast. You can find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon or wherever you get your podcasts.