This year marks a milestone for the state’s legal pot industry. For the first time since voters approved recreational pot use nine years ago, the state of Washington is expected to collect more than $1 billion in marijuana sales taxes and fees over the course of its next two-year budget cycle.

That’s nearly three times what the state collected from 2015 to 2017, the first budget period in which legal pot stores were open for business the entire time.

Still, that money isn’t totally up for grabs. Nearly two-thirds of it is already allocated under state law to specific public programs, following the rough outlines of a plan established by Washington’s 2012 legalization measure, Initiative 502.

While over time state legislators have made some changes to the framework set by I-502, they still have chosen to spend more than half of the state’s marijuana revenue on public health programs, as the ballot measure originally prescribed.

Those preset obligations are partly why Washington lawmakers generally don’t consider pot revenue an ideal source of money for new initiatives. For instance, a proposal to legalize possession of all types of drugs in Washington state, House Bill 1499, wouldn’t tap marijuana tax revenue to pay for expanding drug treatment programs, as a similar law in Oregon does.

“Funding from the dedicated marijuana account is essentially already spoken for … and it funds a lot of stuff that we care about,” said state Rep. Lauren Davis, D-Shoreline, the prime sponsor of Washington’s drug decriminalization bill.

This spring, Washington legislators are expected to pass a new two-year operating budget that spends more than $55 billion. All of the state’s projected pot revenues over the next two years amount to less than 2% of that.

“It’s a lot of money, but in the scheme of the state budget, it’s a relatively small percentage,” said state Rep. Drew Stokesbary, R-Auburn, who serves as House Republican lead on budget issues.

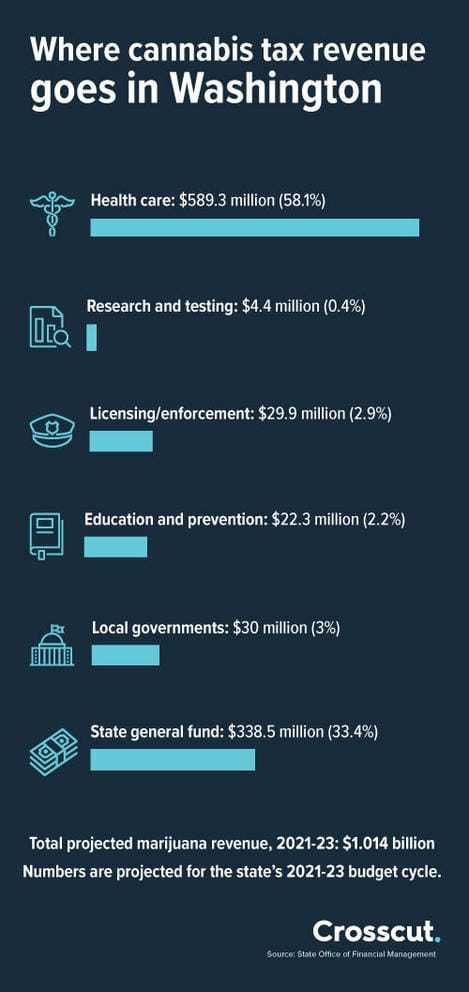

Here’s a more detailed look at the money Washington state collects in marijuana revenues and how the money is currently slated to be spent, according to the state Office of Financial Management. Legislators may make some adjustments to these allotments as they finalize the state’s new 2021-23 budget later this spring.

Health care: $590.3 million

Basic Health Plan Trust Account: $490.4 million

The largest single allocation of pot revenue goes to the state’s Basic Health Plan Trust Account, which is set to receive nearly half the state’s pot revenues over the next two years. That money provides health care for low-income individuals and people who lack health insurance coverage.

It’s the same account where I-502 originally directed the largest share of pot revenue back in 2012.

Alison Holcomb, the lead author of I-502, said setting aside marijuana tax revenue for public health was important when passing the initiative. She said the idea was to show it was possible to address drug use with strategies other than jailing and arresting people.

“We wanted to create a model for what we could do if we treated substance use disorder as a public health issue ... rather than a problem for the police to solve,” said Holcomb, who is the policy director at the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington.

Health Care Authority: $98.9 million

Along the same lines, another sizable share of pot tax money goes to the state Health Care Authority. The agency is directed to use the money to pay for community health centers that provide primary care and dental services for low-income Washingtonians and others who lack access to health insurance. This is the second-largest allocation specified in the state’s cannabis law, again reflecting how the original measure aimed to bolster public health spending.

Licensing/enforcement: $29.9 million

Liquor and Cannabis Board: $24.3 million

I-502 may have decriminalized recreational marijuana use, but it didn’t do so without establishing certain rules. Those included requiring pot businesses to locate a certain distance from schools and playgrounds, and prohibiting marijuana consumption in public. The law also forbids people younger than 21 from consuming the drug.

As the industry has grown over the years, the Legislature has increased the amount of pot tax money that goes to the Liquor and Cannabis Board. The agency is in charge not only of licensing all marijuana retailers, processors and growers, but also enforcing rules against selling pot or marijuana-infused products to minors, as well as regulating the liquor industry.

Washington State Patrol: $5.6 million

This money is for a drug enforcement task force, which is designed to combat illicit marijuana operations, as well as to help prevent the diversion of pot products from the legal cannabis system to the black market. The State Patrol also runs a toxicology lab that ramped up its testing for THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, after the drug was legalized.

Education and prevention: $22.3 million

Department of Health: $21,232,000

This money goes toward cannabis education and public health programs. Part of it pays for a public health hotline that refers people to substance abuse treatment providers. The money also pays for grants to local health departments to develop plans to prevent and reduce youth marijuana use.

Holcomb said one of the other I-502`s goals was to invest in youth drug use prevention strategies that have proved to work, which means going beyond “just say no.” The state’s marijuana law talks about using “evidence-based or research-based public health approaches to minimizing the harms associated with marijuana use,” rather than advocating an abstinence-only approach.

“We believe one of the most successful prevention strategies is providing evidence-based information,” Holcomb said. “Our belief is when people are provided solid information, they do make good choices, especially young people.”

Dropout prevention: $1,060,000

Holcomb said another goal of the initiative was to put resources toward identifying people who are at risk of abusing marijuana and other drugs, then developing strategies to intervene.

One of those programs is the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction’s Building Bridges grants program, which focuses on keeping kids in school.

Grant recipients are tasked with identifying middle and high school students at risk of dropping out and providing interventions to help them graduate. Those interventions can include mentoring, academic coaching and alternative forms of instruction, such as career and technical education courses or online learning.

Public education materials: $40,000

This money goes to the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute to create and update web-based public education materials about the health and safety risks posed by marijuana use.

Local governments: $30 million

As approved by voters in 2012, I-502 didn’t set aside any money for local governments.

Cities and county officials later asked the Legislature for a share of the state’s marijuana tax money. They said it would help defray some of the costs they might accrue from the new law, such as the cost of enforcing the ban on using marijuana in public places.

The Legislature reworked the state’s legal cannabis laws significantly in 2015 and, as part of that overhaul, gave local jurisdictions a cut of the tax money, as long as they didn’t ban pot businesses within their borders.

State general fund: $368.5 million

This is the portion of the state’s pot revenue that flows into the state general fund, meaning it is the portion that can be used most easily to help balance the state operating budget.

The state general fund pays for many things, including K-12 education, which makes up about half the state’s operating budget.

In that sense, pot money is helping support K-12 education in Washington state, said state Sen. Christine Rolfes, D-Bainbridge Island, the Senate’s lead budget writer.

“I am not proud of it, but it is funding our public schools,” Rolfes said.

Right now, state officials don’t want to take away money that pays for education or similarly important state programs, Rolfes said. That means it’s unlikely that legislators will seek to create major new programs with pot revenue — even using this more flexible portion.

Research and testing: $4.4 million

Cost-benefit analysis of legalizing pot: $400,000

One problem with pot being federally illegal for so long is there hasn’t been much research into its long-term effects. I-502 tried to address this gap by setting aside some of the state’s marijuana tax money for research and policy analysis.

The initiative directed the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, a nonpartisan state research agency, to produce reports on the health costs associated with marijuana use versus the health costs associated with criminal prohibition of marijuana. The agency also is supposed to analyze the effectiveness of public education campaigns designed to reduce drug use, and produce reports on how legalizing marijuana affects the criminal justice system.

Each cost-benefit analysis is supposed to be used to inform state policy going forward.

University of Washington: $504,000

This money pays for UW researchers to examine the long-term effects of marijuana use, as well as to analyze research taking place elsewhere on the subject to help inform state policy on cannabis.

Washington State University: $276,000

Like the University of Washington, Washington State University also receives a chunk of money to research the long-term effects of cannabis use and to keep abreast of similar research happening around the country and the world.

Healthy Youth Survey on youth drug use habits: $1 million

This survey asks teenagers and grade-school children about their overall health, as well as their experience with alcohol and drug use.

Department of Ecology: $928,000

This money is for the state Department of Ecology to conduct research into marijuana laboratory testing and accreditation standards.

Testing for pesticides: $1.3 million

The state Department of Agriculture receives this portion of the state’s pot revenue to analyze the amount of pesticides found in marijuana and ensure those levels are in line with state requirements.