When Eli Geranios talked about his hometown during an introductory presentation for his accounting job in Seattle, it was mostly about basketball.

Spokane, after all, is home to Gonzaga University and its prestigious basketball program.

But he also made sure to talk about Hoopfest, the three-on-three basketball tournament that has attracted thousands of people for a summer weekend in the Lilac City. Geranios started playing in the tournament as a child and continued right up to college. His Spokane home was “a hostel” for his visiting cousins who played in the tournament.

“That’s how people are going to recognize” Spokane, which is also the birthplace of Father’s Day, said Geranios, 26.

For several decades, Hoopfest and Bloomsday, a 12-kilometer — or 7.46 mile — road race, have together drawn tens of thousands of participants, community volunteers and spectators. They’re homegrown events that have brought people from across the state — and even the U.S. — to one of the largest cities in the Inland Northwest.

“Having Hoopfest, having Bloomsday … and all sorts of major events draw people in,” said Kate Hudson, public relations manager of Visit Spokane. “It definitely helps market the region and build awareness.”

But with the COVID-19 pandemic putting a halt to gatherings big and small, the streets of downtown Spokane have been quiet for the past two years. Bloomsday went to a virtual race format for 2020 and 2021. Hoopfest was canceled both years.

The hiatus of both events meant lost revenue for event organizers, dwindling tourism activity and lost opportunities for in-person community engagement.

Now as many people seek to return to some form of “normal,” Hoopfest, Bloomsday and other large-scale events are returning to Spokane. Bloomsday was held on May 1, the first in-person race in three years and Hoopfest will follow in June.

While event organizers want to recover the losses from a prolonged hiatus, most are focused on making the events happen and bringing back the community interactions many had lost during the pandemic.

“If we’re able to do this and put on a successful race and community event, it just means the events that follow in Spokane and the region have a good foundation to build from,” said Jon Neill, Bloomsday race director.

With the race promotion for Bloomsday happening when the infectious omicron variant was raging, addressing public health and accommodating participants hesitant about returning to large-scale events were top of mind.

“When it comes to hosting a road race during the pandemic, post-pandemic, we’re going to do everything in our power to make sure we’re safe, and we’re not doing anything that runs counter to personal health and safety,” Neill said.

The losses

Bloomsday attracted just under 40,000 participants in 2019, the last time the event was held pre-pandemic. Hoopfest, which celebrated its 30th anniversary, attracted about 24,000 players representing 6,000 teams that same year.

According to figures from Visit Spokane, a nonprofit tourism marketing organization, Bloomsday generated $12 million in economic activity pre-pandemic — hotel stays, shopping, restaurants and attraction fees — and Hoopfest brought in $50 million.

According to Visit Spokane, Spokane County's tourism activity dropped from $1.3 billion in 2019 to just $580 million in 2020.

Federal tax forms from the nonprofits holding the two events also indicate a significant drop in event revenue. Total revenue for Spokane Hoopfest Association, which organizes the event, decreased from $2.75 million for the 2019 fiscal year ending in September 2019 to just over $1.28 million for the same period in 2020. Revenue did bounce back to nearly $1.6 million in 2021, when Hoopfest was canceled just weeks before it was to start because of rising cases associated with the delta variant.

Riley Stockton, executive director of the Spokane Hoopfest Association, said the organizers offered refunds, but many participants opted to roll over entries to 2022. Sponsors did the same. The organization also received federal and state stimulus dollars.

And that money was needed: Since the cancellation of the 2021 event came just weeks before the scheduled event, the organization still had to pay 70% of the event expenses for 2021.

“We had sponsors that have been absolutely incredible supporting us, staying with us and making sure those lights stay on,” he said. “We truly couldn’t do it without them.”

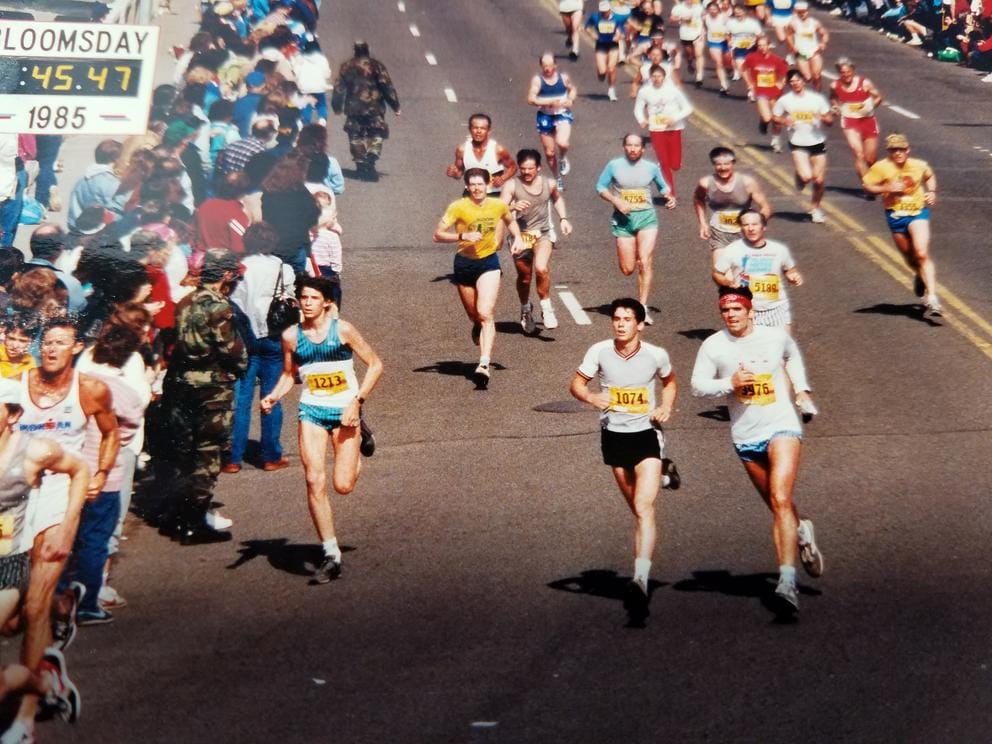

Roger Aldrich, bottom right, approaches the finish line in the 1985 Bloomsday race. Aldrich is known as one of the Perennials, a group that has run every Bloomsday race. There have been 46 races. The Bloomsday race has been an annual event in Spokane since 1977. (Courtesy of Roger Aldrich)

Maintaining community

According to federal nonprofit forms, Bloomsday also saw a drop in revenue — from $1.44 million for the 2019 fiscal year ending in July to $764,999 in 2020.

The organization has brought in money by holding a virtual race, where people run their own course and submit times online afterward, for the past two years.

The virtual race enabled the Bloomsday organization to stay connected with participants during the pandemic, Neill said. More than 20,000 runners signed up for the virtual race in both 2020 and 2021. Race organizers emulated the in-person race experience as much as possible, right down to mailing out finisher shirts.

“Not being able to host a road race as we have done for the previous 43 years, it was wonderful to see that type of encouragement, participation and just excitement [for doing] our race remotely,” Neill said.

Roger Aldrich is a “Perennial,” a group of racers who have run every Bloomsday race.

Don Kardong, a 1976 Olympicc marathoner and Spokane resident, launched the first Lilac Bloomsday Run in 1977. At the time, Aldrich worked as a civil service instructor with the Air Force and enjoyed running races on the weekends. When he heard about a new race happening in downtown Spokane, he signed up.

And Aldrich, now 74, has run every year since.

“There are (nearly) 80 of us that have done it all together. I’m one of the younger ones — there are people in their high-80s and a couple over 90. It just grows on you,” he said.

Many of his memories involve being among the Bloomsday running community, whether it’s running fast enough to keep the elite runners within sight, running the race with his children and grandchildren or hearing spectators cheering him on as he climbs the famed Doomsday Hill.

Aldrich said he was skeptical of the virtual run format. But after doing the race virtually for the past two years, he felt the same sense of accomplishment.

“The culture is such [that] the people won’t let it die out,” he said.

A game at Spokane Hoopfest in 2019. (Courtesy of Spokane Hoopfest)

A basketball town

In 2019, the Spokane Hoopfest Association launched its Hooptown USA initiative to promote the assets, such as Hoopfest and the Gonzaga University basketball program, that have made the greater Spokane area a great basketball town.

The initiative also includes community efforts to cultivate basketball play around the city year-round, such as resurfacing and beautifying the city’s basketball courts. That effort continued during the pandemic, thanks partly to rolled over team fees and sponsorships from years when the event was canceled, said Stockton, the executive director of the Spokane Hoopfest Association.

Stockton is new to the executive director position — he came to it in January — but his connections to Spokane’s basketball culture run deep.

Riley Stockton’s uncle is John Stockton, the Spokane native who played for Gonzaga University and the Utah Jazz in the National Basketball Association. Riley Stockton played in Hoopfest since he was 6, participating through high school. He returned to Spokane after playing basketball for Seattle Pacific University in Seattle, professional basketball for CD Estela in Spain and working for Special Olympics Washington in Seattle.

So he takes seriously overseeing Hoopfest — and the Hooptown USA brand — through its post-pandemic phase.

“I take a lot of pride in not only this organization. I take a lot of pride in Spokane,” he said.

And Stockton can lean on an established track record of success for large-scale community events in this city.

Researchers at Washington State University looked at Spokane’s community events in a recent case study on event safety.

When research started in early 2020, event safety focused on responding to tragic events, such as firearm and gun violence. But the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the researchers to look at the public health aspect of personal safety, said Mark Beattie, one of the study’s co-authors. He is an assistant professor of hospitality and associate vice chancellor for academic affairs at WSU Everett.

The study, which featured interviews with a wide variety of people involved in event planning and the hospitality industry, concluded that Spokane’s success reflected a collaborative and community-based support system. The study noted regular monthly meetings between event organizers and city officials, including police, representatives of the city’s Parks and Recreation Department and the Spokane mayor’s office.

Such gatherings enabled all involved in community events to build trust and communication that allow everyone to be on the same page regarding city and state regulations, such as those tied to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to develop a plan to respond to any situation that comes up.

“It does come down to the people that are involved,” Beattie said. “At the end of the day, it’s about relationships.”

Moving forward

After two years of virtual races, more than 20,000 runners were at the Bloomsday starting line on May 1.

Among those running was Hudson of the Visit Spokane organization.

As a tourism marketing professional, Hudson was thrilled to see people staying at local hotels and dining in local restaurants again.

As a runner, she enjoyed taking in the sounds and sights of the Bloomsday experience — the bands playing along the route, volunteers handing out water and giving finishers T-shirts at the finish line downtown.

“It felt great, it felt energized, it felt we were finally back on track,” she said.

The 2022 figures were below the nearly 40,000 runners who started the race three years ago and less than the 60,000 runners who showed up to Bloomsday at its participant peak in the 1990s.

The lower turnout didn’t surprise Neill, the Bloomsday race director.

“Knowing this is our first year back, there is some hesitancy to jump right into a big community event with that many people in the downtown core and along the course,” he said. “We know we’ll be building back to where we were.”

Bloomsday also offered a virtual race option this year, attracting more than 5,000 runners. The popularity of the virtual run — and the ongoing concerns regarding COVID — made it an easy choice for organizers to offer it this year.

“I think it’s wonderful that people could do it with their comfort level and likewise adapt to their own concerns about health and their own personal safety,” Neill said.

Once skeptical of the virtual race, Aldrich decided to take that option to keep his Bloomsday streak going for another year.

Although he was vaccinated, Aldrich said he still felt he was at risk because of his age and his health. He didn’t want to risk infecting himself or the rest of his family.

“I don’t need to stand down there on Bloomsday morning with 25,000 to 30,000 shoulder to shoulder with no mask on,” he said.

But he was glad for those who decided to run on race day — he ran the course beforehand — and looks forward to joining them in the years to come. He is especially looking forward to 2026, when the race will reach its 50th year.

“I’ll be 78 at that point,” he said. “Hopefully, I’ll still feel good enough and be in good enough shape to do it, no matter how fast.”

Another participant in the virtual run was Beattie of Washington State University. He believes virtual runs and other public health protocols will remain a part of events for some time. It’s a way for event organizers to prevent potential issues and enables the event to be more inclusive and welcoming.

“It’s just about providing a welcoming environment for the space you’re in,” he said.

After seeing Bloomsday’s successful return, Stockton, the Hoopfest executive director, is feeling good about the event next month.

He also expects lower participant numbers — he estimated 60% to 75% of pre-pandemic numbers — but like the Bloomsday organizers, he will be happy to see the event happen, especially after the last-minute cancellation last year.

“However many teams we have, whatever the size of the event, it’s going to be a huge success,” he said. “Some of the people on staff have been planning this one Hoopfest for three years.”

Geranios, the former Spokane resident who now lives in Seattle, will be traveling to Spokane to compete. After coming to Hoopfest as a spectator in recent years, he’ll be on a team with his older brother and two other friends.

For years, Geranios and his brother have told those two friends about Hoopfest and are excited to share the experience with them.

While Geranios hasn’t played much basketball lately, he knows he’ll get right into the spirit when he’s dribbling the ball on the court in downtown Spokane.

“The second the whistle blows, it’s ‘give everything you have’ because you don’t want to lose, and we’re all competitive people at heart,” he said.