“Hope for the best, prepare for the worst.” That is the attitude instilled in me by my parents, who lived through the Great Depression. They taught me that America is supposed to be a land of optimism, but that we also have to deal with setbacks. The past few years have proved that.

Leonard Garfield, longtime head of Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), acknowledged as much in a recent interview with historian Feliks Banel of KIRO radio on the 10th anniversary of the museum’s move from Montlake to South Lake Union. “I used to personally always think that history was constant progress towards getting better, if you will, but I think the last 10 years remind us that there are setbacks. And I think in a global way, the pandemic obviously was a huge setback,” said Garfield.

If 2022 has taught me anything, it’s that the setbacks and the potential for more of them are very real, and that the capacity for resilience and optimism is extremely important, though not easy.

Garfield cites the pandemic era as a setback for Seattle, indeed the world. I agree.

It feels like it should all be over now, but it isn’t. We are approaching the end of three years since a COVID-19 outbreak in a Kirkland, Wash., nursing home first raised alarms in the U.S. in February 2020. But there are still doubts and mixed messages about what’s next. The virus and its variant spinoffs are still with us, as are those millions suffering from its long-term effects. Seattle’s downtown is still struggling to regain its vitality as many storefronts and offices remain empty. Funding for COVID relief is ending as the majority are no longer masking, eager to throw off the yokes of protections that became so politicized and so tiresome. Social distancing is a memory. People aren’t getting the latest boosters. Some predict this won’t be the century’s last and probably not the worst pandemic. It’s a setback that keeps on giving, or rather taking.

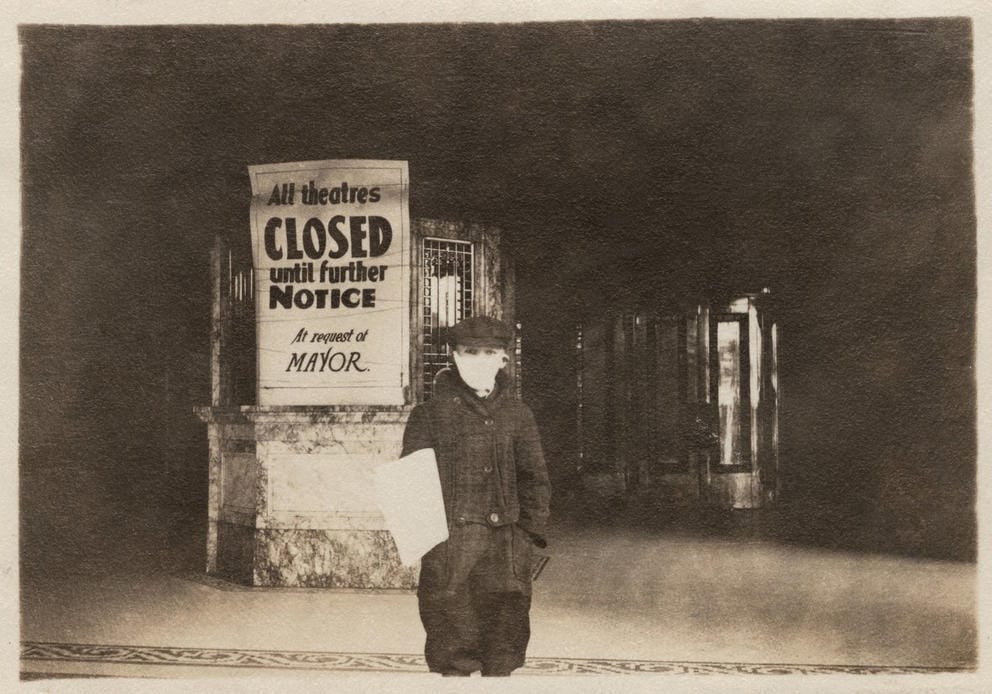

Being lax about COVID-19 precautions won’t help. Looking back to the influenza pandemic of 1918-20, a lesson might be found in how people acted as they believed the pandemic neared its end: with utter abandon and fatal consequences. In Seattle in 1918, we acted boldly briefly, then threw caution to the wind. One might imagine the historical lesson would predict that we would act with greater prudence and caution, but that didn’t happen. The past might also teach us to expect backlash and turmoil in the pandemic’s aftermath. A century ago this country saw the rise of cultural mania, financial irresponsibility, bigotry, racial and ethnic violence. That is happening now as well; where it will take us we don’t know.

For all our progress in medicine and science since 1918, we have repeated most of the mistakes of a century ago, despite the opportunity to know and behave better for longer.

There are looming challenges even bigger than the pandemic. In the most recent season of Mossback’s Northwest, we did an episode that was a paean to British Columbia artist Emily Carr, whose paintings of Pacific Northwest forests in the 1930s and ‘40s are exceptionally moving. She brings sky and red cedar to life by capturing the networks of intertwined energies.

Perhaps it should be no surprise that climate activists protesting a pipeline in Canada chose to bring attention to their cause by spattering one of her paintings in a Vancouver, B.C., art museum with maple syrup. Paintings by Van Gogh and Vermeer have seen similar attacks. That trend has felt like a cultural backstep, even if it might be for a good cause — and a bit ironic since Carr’s artwork, “Stumps and Sky,” was her statement about the Northwest’s unique environment and damage done by the hands of humans.

Many of Carr’s paintings do not shy away from environmental destruction. She painted clear-cuts and gravel pits along with lush old growth. She believed the earth could heal such scars. That might be commendable, but it hardly matches the potential global harms of human-caused climate change. Red cedars were a particular star of Carr’s paintings, but are now a fading icon of Cascadia where die-backs, extreme weather events and climate change appear to be diminishing the trees in their native habitat.

Carr was right that nature itself will endure, but the things we hold sacred in this region, and the mythos she helped us see with her work and our own lived experience in nature, might be altered or exterminated. This year, I certainly felt anxiety with Seattle's warm, dry and smoky autumn. One can feel change is afoot. If the salmon, orca and red cedar go, will our new symbols be invasive green crab, palm trees and glacier-free volcanoes? It’s unsettling.

This year also highlighted threats to our democracy, something that was once considered an unqualified good. Now a substantial number of influential folks seem to think it's overrated? A former president has called to “suspend” the Constitution! The battlefield includes elections and free speech on Twitter. Recent history reminds us that free speech is not always free and it that has consequences.

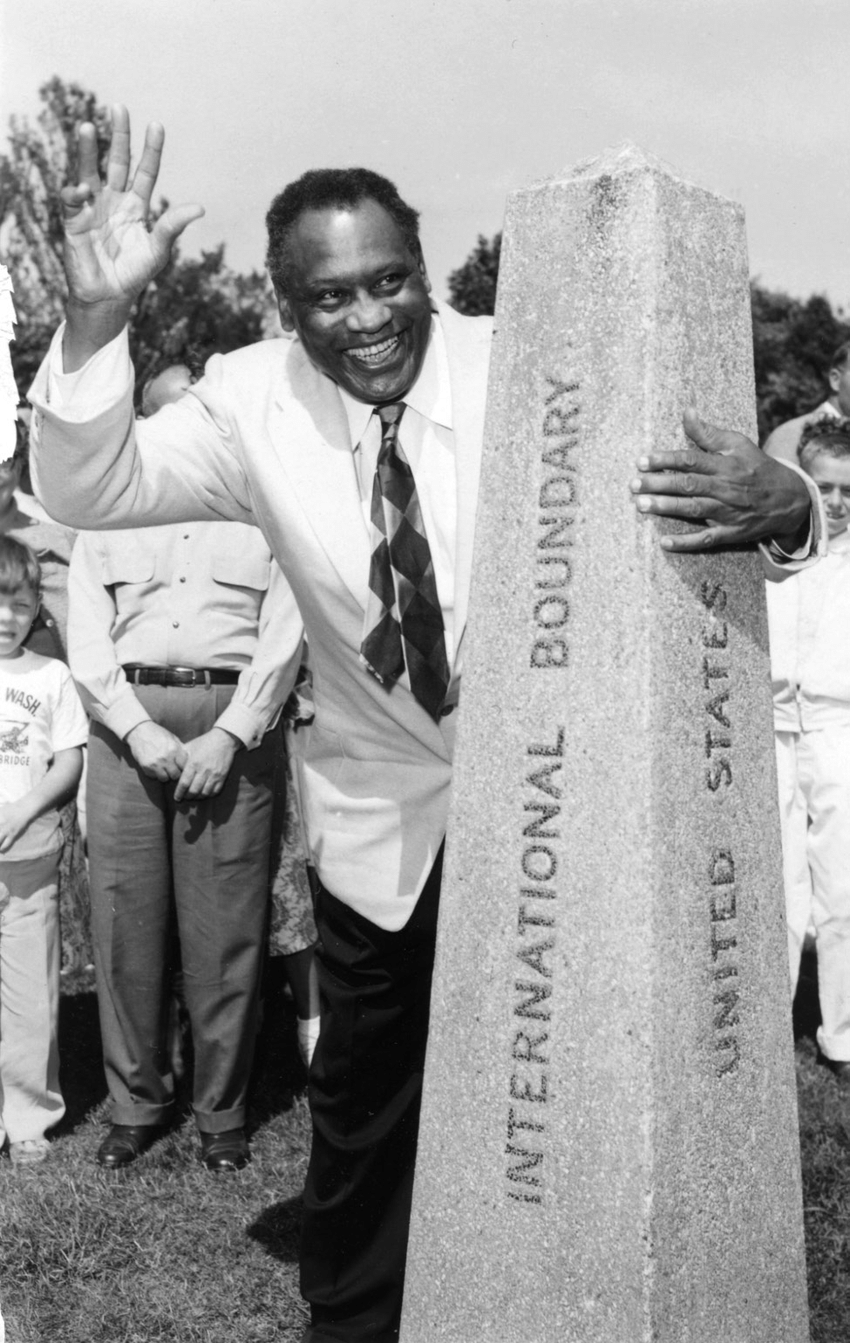

Our Mossback episode on the singer and civil rights and lefty political activist Paul Robeson recalled a battle for free speech that came to the Northwest in the early 1950s. Robeson's support of the Soviet Union and China triggered the U.S. government to seize his passport so he could not travel abroad — even to Canada. He was also prohibited from speaking at Seattle’s Civic Auditorium. So he gave speeches and concerts at the U.S./Canada border, advocating for peace and equal rights to an international audience at the Blaine Peace Arch in 1952.

Robeson eventually got his passport back. But his career was badly damaged by the travel prohibition, the Red Scare, blackballing, harassment, and his own disillusionment with communism and the Soviets. He fought for the right to sing and speak anywhere in the world, but the effect of the barriers thrown up by the U.S. government helped his career fizzle and his health suffer. In the end, he became a recluse and was successfully silenced.

This year also recalled for me a moment from local history that touched on another aspect of the free-speech debate, the murders of Charles Goldmark and his family. That tragedy came about because of loose speech, a false accusation against Goldmark's father. It was a rumor seized upon by an unbalanced individual who invaded their Seattle home and brutally killed the family on Christmas Eve, 1985. The killer believed Goldmark was leading a communist revolution. He was in fact a civic-minded attorney.

Rumor, false narratives, and the virulent political hatreds fed in small-group hothouse atmospheres and online can feed toxic free speech. Just hop on social media or cable TV to witness the poison. The Goldmark story came rushing back to mind in the wake of the hammer attack on House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband Paul.

Ye, formerly Kanye West, can spew hate for Jews, Holocaust denial and love for Adolf Hitler on TV. The attempt to erase what actually happened and replace the truth about the Holocaust with an alternate unreality is appalling, more so because the Nazis themselves documented what they did so well: They filmed and photographed it, they kept records of their crimes, they bragged about it. Proof from the Jewish victims in places like Seattle’s Holocaust Center for Humanity exhibit artifacts from camps and survivors. They actively support the act of remembering, not faking, real history. The mainstreaming of such false conspiracies and a rise in hate crimes and expressions of racism and antisemitism are connected.

This year my story on a Nazi intelligence officer who came to the U.S. and visited Seattle in 1938 to take the temperature of Americans regarding Jews and the country’s political mood was previously untold history. The German SS officer was wined and dined by some members of Seattle’s German American community who, he reported to his Berlin higher-ups, were antisemitic and pretty like-minded in terms of German policies. The locals advised him that Germany might want to tone down the violence against Jews as it was a bad look for the Third Reich. Tempered Hitlerism was apparently OK.

The spy, Herbert Mehlhorn, an officer in the Nazi SD security service, scorned their advice and went on to play a pivotal role in the extermination of Jews in occupied Poland. It boggles the mind that prominent Seattleites entertained such a man in their homes and took him to sail on Lake Washington and visit Mt. Rainier. True, they didn’t know his future, but they must have suspected his purpose. He wasn’t that secretive, and by 1938 many people could see what where Hitler was heading.

That same year, an American speaker from Seattle, Roy Zachary, faced 700 protesters in Spokane who showed up to oppose his pro-Nazi speech on behalf of the Silver Shirt fascists. One protester was a young daughter of Spokane, Margaret Weaver, who had previously helped plan an anti-Nazi action to tear down a swastika flag in a famous New York incident. She was arrested in her hometown for blocking the sidewalk outside of Zachary’s talk. “Stanford Girl Assails Fascism,” said a headline in the Spokesman Review, “Prefers Jail to Fascism.”

Democracy has been threatened before, hate speech has previously filled the airwaves, longstanding racism and ethnic hatreds have burst out and proliferated like a pandemic virus, moving, mutating and throwing up obstacles to what we thought of as renewed normalcy. Slow-moving self-destruction, as with climate change, has become almost a modern norm.

To me, 2022 and our setbacks are a reminder that optimism lies in the belief that we can beat the challenges we face by not taking normalcy for granted; by looking at it closely to see how we can make a better, if not perfect, world for ourselves and future generations. Waves of change and challenge are a constant, progress is not. Many of our big setbacks are often self-inflicted or made worse by our response. That offers the hope that it's within our power to overcome what lies ahead.