The Seattle Department of Transportation reports stellar results from one of its most ballyhooed traffic “rechannelization” projects, on Rainier Avenue South in Columbia City and Hillman City. Now it proposes to extend that success to a longer stretch of what’s often called “the most dangerous street in Seattle.” But vexing questions remain.

In August 2015, SDOT dropped the speed limit from 30 to 25 miles per hour between Alaska and Kenny streets, doubled red-light durations, and shrank the four traffic lanes there down to two, one in each direction, plus a turn lane. That’s meant slower speeds and more congestion, with backups up to four blocks long — and more safety.

Nearly 6,000 fewer drivers, 27 percent of the old traffic load, now use Rainier daily. They seem to have diverted to Martin Luther King Jr. Way, which gained more than 8,000 vehicles a day. SDOT reports finding no evidence of significant cut-through traffic on the intervening residential streets, but residents say otherwise.

“The pressure on side streets in Columbia City is off the charts,” says Ray Akers, who lives on one of those streets. Jim Curtin, manager of SDOT’s Vision Zero Safety Corridor Project, credits that pressure to light-rail passengers parking on nearby neighborhood streets.

SDOT did not tally collisions on those side streets and alternate arterials. But it found they decreased by 15 percent on the rechanneled section of Rainier despite a 25 percent increase in rear-enders, reflecting the new stop-and-go conditions. Most gratifyingly, SDOT recorded not a single a single head-on collision, traffic fatality or serious injury during the year monitored — versus an average of nine serious injury accidents a year before.

That perfect record ended with a crash this summer, after the review was done. A driver racing down that middle turn lane rammed a bus and was badly hurt. With traffic slowed, that empty, extra-wide center lane tempts a few impatient motorists.

Adding irony to injury, that turn lane was installed at the expense of an amenity cyclists are still pining for: a safe, direct, reasonably level bike route through Seattle’s cycling-disadvantaged southeast quadrant. The current routes there have serious handicaps: a 300-foot climb up Beacon Hill’s Chief Sealth Trail; sharing narrow lanes with cars on Lake Washington Boulevard, plus steep hills at most exit points. A neighborhood greenway — a linkage of residential streets with such measures as improved signage and speed bumps to create calmer traffic — is in the works midway between Rainier and MLK Way; it zigs and zags and rises and falls.

“Greenways here involve invariably a ton of hills that aren’t for everybody,” says Deb Salls, executive director of Bike Works, a Columbia City-based nonprofit that promotes cycling and equips low-income residents for it. “It’s not like putting a protected bikeway down the arterial that cuts through all the neighborhoods in the South End. Rainier is the one direct route through the valley.”

In 2015, officials decided that the fast, reckless driving on Rainier would make bike lanes unsafe but insisted the omission was only provisional: “This is a pilot project, to see how drivers adjust,” SDOT's Curtin said then. “We’ll review it when we do the full corridor.”

Now, with traffic calmed, that opportunity is approaching. After months of surveying local wishes, SDOT is preparing to put the longer stretch from Hillman City to Rainier Beach on a diet. It’s offered two alternative designs.

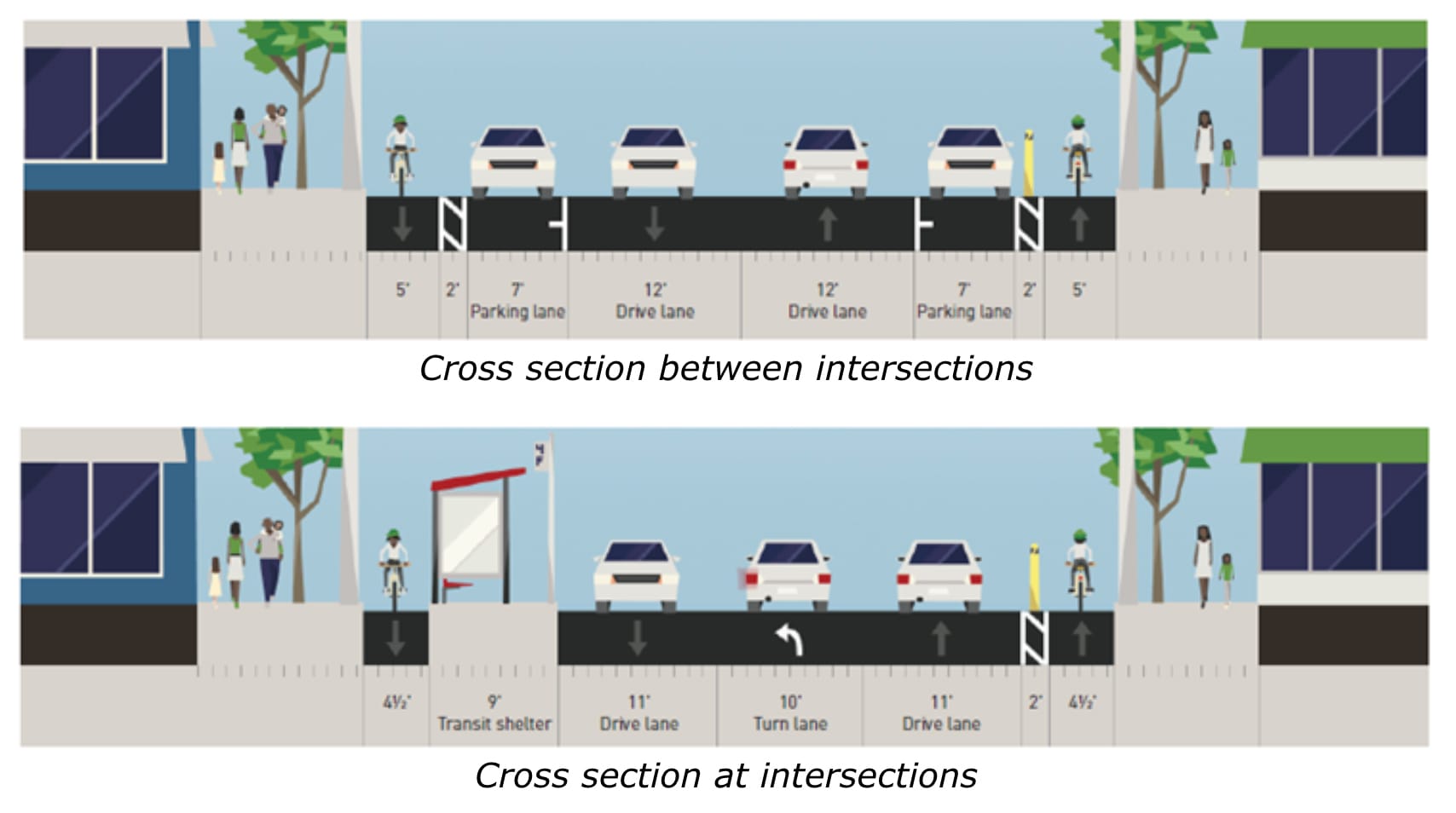

The first would extend the single driving lanes and middle turn lane (with no bike lanes), but would replace parking on one side with a dedicated northbound bus lane.

The second would have no bus lane, and turn lanes only at intersections, leaving room for bike lanes shielded by parking lanes, as on Broadway on Capitol Hill and Second Avenue downtown.

The second scheme offers transit and parking benefits in addition to safe bike lanes, but SDOT's presentation in outreach materials understates or even, at times, misrepresents those effects. The department warns that adding bike lanes may “reduce bus reliability in both directions,” but Curtin says that “both options would benefit transit significantly” because new curb bulbs would save buses from pulling in and out of traffic. In an August survey SDOT asked if respondents would “still prefer” that option “knowing that it will reduce some on-street parking.” In fact, the bike-lane scheme would preserve parking on both sides of Rainier Avenue, whereas the bike-free option would eliminate it on one side.

The August survey continued in a push-poll tone, asking if respondents “still prefer” bike lanes “knowing that” the city’s Bike Master Plan doesn’t include them and that they may slow traffic flow. “It seemed like they were trying to talk you out of a protected bikeway,” says Salls.

A survey earlier in the year likewise gave cycling short shrift. It asked what “impediments” prevented residents from walking but did not ask what hindered biking. Even so, when asked how they would prefer to get around, biking, not walking or transit, was the mode the largest share of respondents said they wanted to start using.

That survey also did not include bike lanes among the roadway improvements it asked residents to prioritize. Nevertheless, says James Le, the Rainier corridor’s project manager, about a third of the respondents wrote them in. SDOT didn’t include those responses when it reported the results.

Why did that survey neglect bike options? “The bicycle concept wasn’t something we considered at that time,” says Le. That they’re considering it now is “mostly based on what we heard from community” — which is also what they heard from the community two years ago.

Curtin acknowledges the surveys’ faults but says, “Alternative 2 [with bike lanes] really is our ultimate vision for the corridor. Ultimately, we would like to take that alternative all the way north. It depends on our budget.”

That’s where the rubber doesn’t meet the road. Le sees no prospect of inserting bike lanes in Hillman City and Columbia City anytime soon: “It’s the cost.” In its summary of the alternatives, SDOT notes that the bike option “exceeds current project budget and may need to be constructed in phases with yet to be identified funds.”

In 2015, when SDOT proceeded without bike lanes in Hillman City and Columbia City, its director, Scott Kubly said reassuringly that they would be “easy to add later — you just lay down some paint.” But as project manager Le notes, it’s not that simple: The bike lanes must cut through curb bulbs and bus islands, sometimes disturbing traffic signals, sidewalk trees and fire hydrants.

Such cost concerns didn’t stop the city from installing buffered cycle lanes on Dexter Avenue North five years ago — and then spending $6.1 million on a parallel “world-class” cycle track on Westlake Avenue North.

Southeast Seattle residents have long chafed at unequal treatment in bike lanes, transportation and other city services. But they’ve also long clamored for more pedestrian and vehicle safety on Rainier Avenue, and the city has heard that call. It plans to settle on a design for the Rainier Beach road diet by year’s end and build it next summer.

“Our main goal is to precede as soon as we can,” says Curtin. “We can’t wait for everything to be perfect. We’re always open to improving, mixing and matching elements.

"I don’t see us being done with the Rainier project for a really long time.”