Across the United States, a once-in-a-decade power play is underway. Its outcome could determine which party has an electoral advantage for the next 10 years on both the national and the state level. In states like Washington, the shifting of a few districts could earn or cost a party the legislative majority.

After every census, legislative and congressional districts are redrawn to ensure each has about the same number of people. In some states this is a partisan, gerrymandered, undemocratic mess. But in Washington state, lines are drawn by a bipartisan commission with citizen input, which means that both parties always have a say.

Going into this process, both parties identify where their voters live based on past elections, then propose new districts that encompass their voters, creating safe, partisan districts. The party that gets the majority of safe districts can enjoy an electoral advantage. But this year, to get that advantage, a different approach might be necessary.

The dominant party could be the one that proposes new districts based not on where its voters are, but on who and where its voters will be in 2024 and 2028.

That’s because in some areas of Washington how people voted in the past isn’t necessarily a reliable indicator of how they will vote in the future. Party preferences are now fluid. Suburbs that traditionally voted Republican now send Democrats to Olympia and Washington, D.C. Pro-logging Democrats now elect Republicans. Depending on redistricting and how the two parties position themselves on issues going forward, a few Democratic districts by decade’s end could swing Republican, just as Mercer Island has swung Democratic. That isn’t hypothetical. Depending on the new legislative district lines, the swing to the right that we’ve seen in Grays Harbor could happen in new districts that include Everett or Parkland.

Growing up in southwest Washington, I remember Grays Harbor reliably voting for Democrats like Scoop Jackson and Warren Magnuson. But the Democrats who repeatedly returned Julia Butler Hansen and Don Bonker to Congress from the ‘60s through the ‘90s, elected a Republican in 1995 and have continued to do so since 2012; in 2016 and 2020 they voted for Trump. This partisan fluidity floats atop a reality that Butler Hansen Democrats, whether in the Harbor or Spokane or Pierce County, are not “Jayapal Democrats,” just as many of the Bellevue-Mercer Island Republicans who sent Steve Litzow to Olympia are not Trump Republicans.

This shift among voters mirrors a shift within the parties themselves. “Jayapal Democrats” are pulling their party to the left, while Republicans are appealing to some of the Democrats feeling abandoned. In a recent interview, state Senate Minority Leader John Braun talked proudly about how the working families tax credit “made it over the hump [in this legislative session] because Republicans led on that issue.” House Minority Leader J.T. Wilcox said, “Republicans, I think, represent probably the bulk of low- income working families. Those are the people who are getting left behind a little bit now, especially when we are hearing this constant talk about a regressive tax system and progressive values. I cannot tell you how angry, honestly, I am that many of the actions [passed this year by Democratic legislators] are incredibly regressive and are the most painful for … working families that have to commute.”

A Republican legislative leader told me during session that Washington’s Republican Party is “now a solidly working-class party.” If that’s true, during this year’s redistricting Republicans might scrutinize some Butler Hansen Democrat districts that 10 years ago weren’t of interest, but that could start voting Republican in four to 12 years.

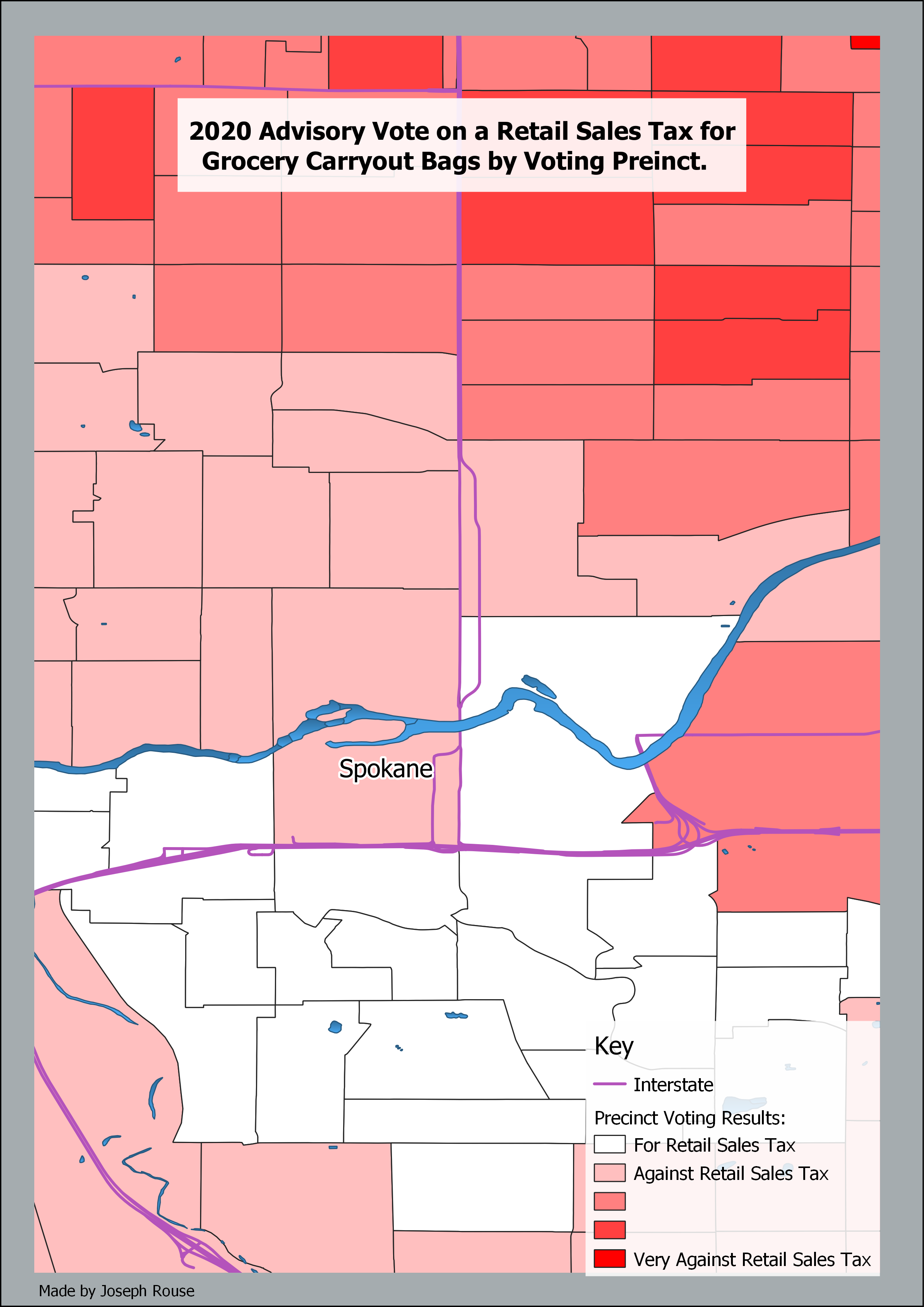

Consider Spokane. There, the South Hill neighborhood, south of Interstate 90, is knit together with tidy Tudors, midcentury ramblers and a good number of Colonials and Craftsman homes all tucked behind proper landscaping. The neighborhoods north of the Spokane River, like Hillyard, are more tightly packed with postwar bungalows. Given conventional thinking, one might predict South Hill would vote Republican and Hillyard would vote Democratic, but not so much. In my 2016 gubernatorial campaign, I beat or tied Inslee in precincts north of the river and lost South Hill. In 2020, the advisory vote on the new grocery bag tax — opposed by Republicans — passed in South Hill and failed north of the Spokane River.

A similar divergence on taxes can be seen in the results of the Democrat-favored cap-and-trade initiative of 2018, which would have raised the price of gas and heating fuel. It failed in working class-military Parkland, but passed in the tonier suburbs of Redmond, Sammamish and Issaquah.

These results are consistent with a late April, statewide, internal Republican poll in which respondents earning under $100,000 a year cited taxes after homelessness as the state’s most important issue. Respondents earning over $100,000 a year ranked taxes fourth in importance after homelessness, the pandemic, the environment, and only then rising taxes.

Republicans trying to retake suburban communities by arguing against rising taxes are fighting a 21st century battle with a 20th century battle plan. But Democrats are demonstrating a similar disconnect by emphasizing diversity, equity and police reform, which, according to the internal poll, were among the lowest concerns of respondents earning under $100,000 a year, a conventional Democratic stronghold.

I am not suggesting Republicans walk away from what were once Republican suburbs. That’s where the votes are, and the voter realignment underway is uncertain and will be gradual. And Republicans can still win there — my analysis of how Sammamish, Mill Creek and Bellevue are now voting suggests a traditional Washington state Republican who provided pragmatic, center-right approaches to homelessness and the environment could win in those communities.

I am suggesting, though, that the road to a statewide Republican legislative majority (and maybe even the governor’s office) might not involve running the suburban table, but instead, in winning back a few historically Republican suburban seats and flipping a few traditionally Democratic communities.

Flipping communities like Everett and Parkland, both of which voted for Joe Biden, will not be easy. It might require policy adjustments, such as opposing right to work for private sector and first responder unions, or developing market-based ways to provide medical care to all children. But, depending on how districts are redrawn, maybe a few communities could be flipped simply by reaching out to people who feel abandoned by “Jayapal Democrats” who raise their taxes, who jeopardize their jobs for environmental measures that will yield no environmental gain and who champion the right of guys to camp on their kids’ playfields. If Republicans can focus on the concerns of these “working families who have to commute,” in 2024 or 2028 some unexpected seats could be in play.

All this is based as much on my hunch as it is on data, but if I am right, the Republicans proposing redistricting maps might advocate for a few solid “Butler Hansen districts,” which, depending on how party and voter migrations settle out, could vote Republican before the decade is over.