While many students at the University of Washington prepared to return to in-person classes in January, Madison Sasaki wanted to continue her courses from home.

As someone with a weakened immune system, Sasaki fears contracting COVID-19 and bringing the virus home to her partner, who is immunocompromised and gets dialysis treatments several times a week for their kidney disease.

“I toyed with the idea of withdrawing from this quarter, but I feel like I'm already so behind in my college career, that I don't really have that option anymore,” said Sasaki, a third-year drama performance major.

For some students, faculty and staff, in-person learning has strained their mental health by forcing them to prioritize academics or work over potentially exposing themselves or their loved ones to the coronavirus. While many people are starting to talk about life after the pandemic, for others, COVID-19 continues to present anxiety and fear.

The pandemic has proved difficult for many Americans, but young adults have felt the biggest mental health impact. Between August 2020 and February 2021, anxiety and depression increased from 37% to 42% for adults 18 to 29 years old, the biggest increase compared with other age groups, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

Social anxiety particularly increased, said Natacha Foo Kune, counseling psychologist and director of the UW Counseling Center.

Foo Kune compared the never-ending aspect of the pandemic to moving to a new place and needing to figure out habits and routines. During a pandemic, however, people can’t settle because of constant changes, including unexpected quarantines, breakthrough variants, school shutdowns and event cancellations.

“When we know that something will end, it’s easier for us to cope,” Foo Kune said.

Professor James Pfeiffer lectures during his Anthropology and International Health class at the University of Washington, March 8, 2022. Pfeiffer’s class is still hybrid, with some students attending virtually. (Jason Redmond for Crosscut)

The UW pushed back its in-person return date several times until it was finally set to resume on Jan. 31. That week, Washington state was coming down from the peak of COVID-19 cases, with a weekly average of more than 9,100 cases a week per 100,000 people.

The university’s decision to resume in-person classes put the choice on professors to determine whether their classes will be held in-person or virtually.

“I want to do what's right for my students, because at the end of the day, they're the ones who are learning in this class,” said Matthew Mitnick, a teaching assistant in the political science department and a graduate student in UW’s public administration program. “I feel like if I'm not able to accommodate everyone, I'm failing them.”

Most UW faculty and graduate instructors received news of the return to in-person learning at the same time as students, making it difficult for them to change class modules and adjust for student disability or health accommodations without prior notice. Many students said they had to wait up until the weekend of Jan. 29 to find out if they needed to return to campus.

James Pfeiffer, a professor in UW’s Department of Global Health, said he was bothered that staff and faculty weren’t included in discussions about returning to campus. Although omicron cases have since decreased, Pfeiffer worried that bringing hundreds of students into confined spaces would increase transmissions within the university community.

UW medical experts said COVID transmission is low in the classroom because of the precautions the university has in place. These include vaccination requirements, supplying masks to students and staff and frequently cleaning shared spaces, said university spokesman Victor Balta.

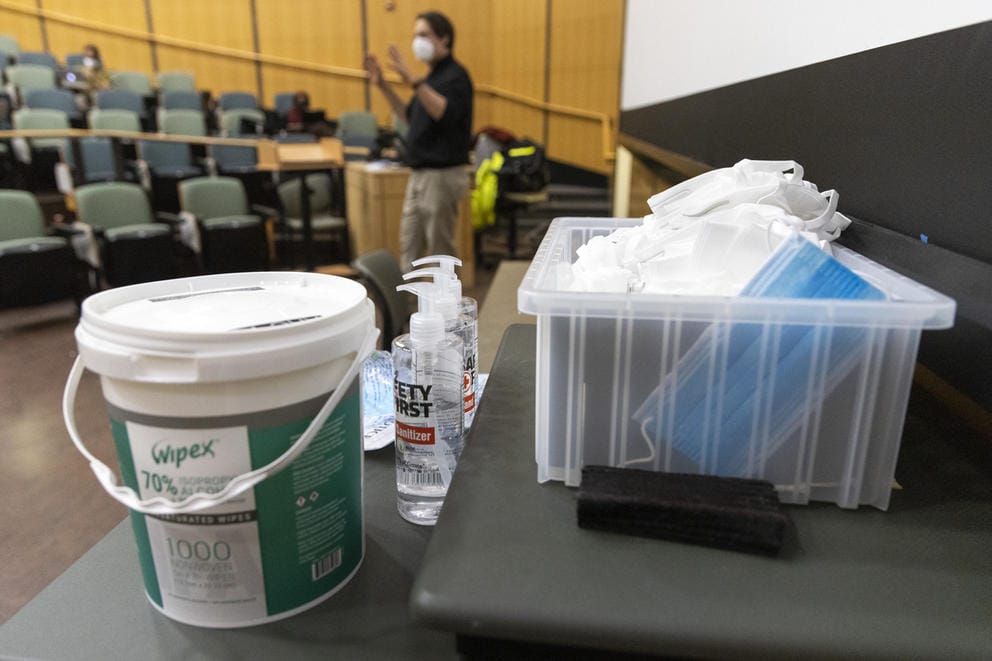

Disinfectant wipes, hand sanitizer and face masks are pictured during professor James Pfeiffer’s class at the University of Washington on March 8, 2022. (Jason Redmond for Crosscut)

Since winter quarter began in January, Gov. Jay Inslee announced Washington state’s indoor mask mandate will be lifted March 21, and this applies to most public indoor spaces, including schools. The relaxing of restrictions comes after a decline in COVID-19 cases during February and mirrors what is happening with policies in in other states and in the federal government.

Despite these developments, some students have raised concerns that January was too soon to return to in-person classes.

“I think people just don't realize the decision we're making. When we do choose to have in-person classes we are either choosing to sacrifice our education or we're choosing to sacrifice our family or our health,” said Celeste Padilla, a UW sophomore majoring in environmental science and terrestrial resource management.

Although most UW classes had to remain online during the first weeks of winter quarter, laboratory classes required in-person attendance. In Padilla’s chemistry lab class, students were required to change into new face masks when they arrived, in addition to wearing standard protective gear like gloves, goggles and lab coats.

Padilla felt safe going to this class, she said, because a majority of students got weekly COVID tests and notified others of their results. She feels less safe in her lecture classes with over 200 other students. During her in-person lecture classes in fall quarter, Padilla said she would get constant phone notifications telling her that she had been exposed to someone who’d tested positive for COVID.

Students are allowed to request accommodations based on their circumstances by speaking with their professors or by getting approval from the university’s Disability Resources for Students center. These requests can take between one to five weeks or longer to process.

Currently, students’ accommodation requests will not be granted until spring quarter, said Toby Gallant, Associated Students of UW director for the Student Disability Commission. Some group members told Gallant that the disability resource center advisers had asked students wanting to continue remote learning if they had considered deferring a quarter.

With the long response times for accommodation requests, Gallant said students of the disability community are feeling “disposable.”

The Disability Resources for Students center did not return calls for comment.

Student Raiyan Khan attends professor James Pfeiffer’s Anthropology and International Health class at the University of Washington on March 8, 2022. (Jason Redmond for Crosscut)

The Student Disability Commission is urging the administration to ensure remote and hybrid options indefinitely to make education more equitable beyond the pandemic. The university met with members of the ASUW Disability Commission in early February, said Michelle Ma, associate director of UW News. The commission and administration agreed to continue meetings to address student needs on how to make future decisions regarding COVID-19 adjustments.

ASUW’s Gallant said he benefits from in-person learning as someone with anxiety, depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but acknowledges this is not the case for all students.

“Let people have autonomy and agency over their educational experience. And if they feel safest in the classroom, so be it,” he said. “But if they feel the safest at home or remote, let them have that opportunity and still receive the equitable education experience that we were promised.”

The return to in-person learning hasn’t been easy for faculty, staff and students with children, either.

Like other faculty with young children, Benjamin Brunjes had to juggle parenting while teaching classes remotely. As an assistant professor in UW’s Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance, Brunjes also found himself leading his eight children through their own online classes. Juggling the two, in addition to trying to build community with 60 students he mostly hasn’t met, has been an additional stressor, he said.

“The key right now is being flexible and nimble: build an environment where there is trust and communication, give everyone the benefit of the doubt, and do what you can to keep people safe,” Brunjes wrote in an email.

The increase in stress, anxiety and depression seen over the past two years likely wouldn’t exist without the pandemic, said Dr. Jane M. Simoni, a clinical psychologist and professor and director of clinical training in UW’s psychology department. While many hoped for normalcy after the COVID vaccine rollout last spring, vaccine hesitancy, variants and the uncertain nature of the pandemic have engendered a sense of hopelessness, she said.

“People in general want a sense of control in their life. They want to feel as if they're experiencing something that's predictable, and that's just everything that epidemic was not,” Simoni said.

If students’ anxiety or depression worsens or persists, Simoni and Foo Kune of the UW Counseling Center both recommend accessing therapy, either on campus or through their health insurance providers. Students can access mental health services on campus through the counseling center, but some students report that accessing assistance quickly can be difficult.

Julie Emory, a first-year graduate student in UW’s information management program, said she tried booking a 30-minute appointment in January after receiving news that her grandfather died as a result of COVID-19. The earliest available appointment was a month away.

Foo Kune said the center allows for students to schedule appointments two weeks out to avoid cancellations. Students can call the center to be put on a cancellation list to be seen quicker in case an appointment is canceled.

“Most people are going to do well; they're resilient,” Simoni said. “For some people, it will be difficult to recover.”