Three small signs affixed outside Jodi Opitz’s music rehearsal business in Seattle’s SODO neighborhood are costing her $500 a day in fines.

Those notices — all posted without city approval — are usually enough to keep unwanted motorists from parking along Occidental Avenue behind Opitz’s Seattle Rehearsal, which has 31 studios that she rents to music groups including some of the city’s most well-known acts. The vacant parking spaces are a stark contrast to the rest of SODO, a cramped mess of parked cars that compete daily for every open inch.

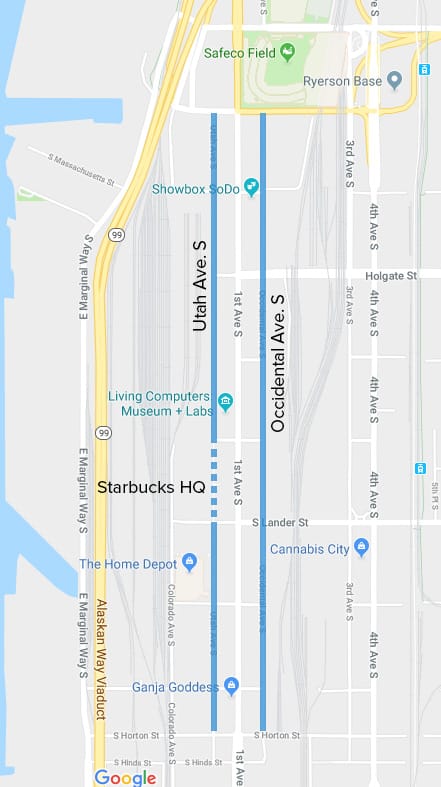

SODO’s population of visitors and workers has multiplied in recent decades as the area swelled with redevelopment, thanks in part to new baseball and football stadiums and to Starbucks moving its global headquarters to Utah Avenue South. That growth, further fueled by the economic recovery during this decade, has come with a big consequence: Finding a place to park in SODO past dawn on an average weekday is now nearly impossible.

Opitz, though, is firm in defending the right to keep open the land behind her property. “I can’t play around with this; this is my livelihood,” she says.

Yet the space behind her building isn’t actually hers to control because it’s public property, according to the Seattle Department of Transportation and attorneys for the city.

Those city officials deemed Opitz’s signs a “public nuisance” for creating “confusion” and violating neighborhood parking rules. Three years ago, they began to impose the hefty daily fine after Opitz defied their warnings for nine years. Her outstanding balance now exceeds $545,000 and counting.

By law, the city argues, the right of way that lines Occidental immediately outside Opitz’s doorstep is to be kept open for public parking. But the city didn’t really enforce its authority on that issue for many years, neighborhood business owners say.

Opitz is fighting the city in court, arguing a constitutional right to control the space behind her property so that she can keep accessing her loading doors and running her business as she says she did long before the city intervened. She says the bands that use her business rely on unobstructed access to her loading dock 24/7 in order to rent her custom rehearsal spaces and store their instruments and equipment.

Opitz — who also operates an event space called Sodo Pop on the First Avenue side and lives in the building as its caretaker — fears she’ll be forced out of business in as little as two years if she is forced to comply with the city’s parking regulations.

Facing the same pressure from the city to keep rights of way clear, dozens of similarly situated businesses off Occidental and nearby Utah Avenue, which runs parallel across First Avenue to the west, have reluctantly succumbed to a new status quo. A hodge-podge of sometimes contradictory city signage allows public parking behind their properties — at no charge, which attracts the daily invasion of commuter cars.

If we can’t solve this, we have no hope.

The congested rights of way have caused continued frustration and ongoing problems, several business owners told Crosscut, but they say the city hasn’t made a concerted effort to address the parking and access problems.

“It never felt like they wanted to make it work for the business,” said Ami Watson, a former manager at Carpet To Go, which had a SODO location next to Opitz’s property but recently closed. (The owners, who now operate in Bellevue, didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

“It was always about street parking. I felt like they were trying to get street parking,” Watson said of SDOT.

Among the businesses’ complaints, they say they frequently can’t access their own buildings for routine deliveries because loading areas are illegally blocked by the parking public. Enforcement of parking laws is inconsistent, they’ve observed. And they also say that when they try to stake a claim over their neighboring right of way, as Opitz has done, they receive threatening letters from SDOT or parking tickets from Seattle Police.

“I have had trucks leave because there’s no access. It’s challenging to be able to do business down here,” said Terry Wick, vice president of O.B. Williams, an architectural woodworking company that has operated between First Avenue South and Utah Avenue South in SODO for more than a century.

Several SODO business owners said they, like Opitz, urgently want a compromise from City Hall — such as an annual permit granting them authority over their neighboring right of way or the option of purchasing the space outright. But they say the city rejected those ideas and has ignored their persistent requests for a viable solution.

Instead, the businesses were offered only existing signage to accommodate varying degrees of public parking or load-only zones. But the standard signs, property owners say, don’t mesh with the nature of their industrial businesses, which rely on frequent deliveries and ready access to loading docks.

“If we can’t solve this, we have no hope,” Opitz says.

A once-sleepy neighborhood that boomed

It wasn’t until perhaps 12 years ago — as growth in SODO escalated — that the city started asserting a vested interest in its rights of way in SODO, several business owners said.

“We made a concerted effort about five or 10 years ago to clean things up a little bit down there,” acknowledged Mike Estey, SDOT’s parking program manager.

Before that, SODO business owners operated with relatively little interference from City Hall. “SODO benefited from — and suffered under — a very laissez-faire regulatory scheme from the City of Seattle for a long time,” said Darby DuComb, a land-use attorney who works at a private firm in south SODO. She also worked for nearly 18 years in City Hall, most recently as a deputy city attorney and former chief of staff for City Attorney Pete Holmes.

“SODO never needed that level of service from City Hall, but now it does,” she said.

A view of Seattle's downtown as seen from railroad tracks that run south through the SODO neighborhood off South Lander Street. (Photo by Kristen M. Clark / Crosscut)

Throughout the 1900s, trains would rumble through SODO — Seattle’s historic hub for manufacturing and industrial commerce south of downtown — on north-south rail lines that ran parallel to many of the buildings, barely an arms-length away. Businesses would get their wares picked up or dropped off directly from boxcars with uninterrupted ease.

The trains still run through some parts of SODO, primarily to usher wares to and from the Port of Seattle. But sometime by the ’90s, the trains stopped running on tracks that had lined Occidental and Utah avenues.

The needs of businesses lining those streets to transport their goods didn’t go away, though. The businesses turned to trucks and cars to make their deliveries using the same stretch of public right of way alongside their buildings that the railroad used to occupy.

Opitz, of Seattle Rehearsal, said that’s how it had always been since she first started working in SODO in 1991 and moved her business into her current building between First Avenue South and Occidental in 1995.

“I have always had — including the previous owner, since the 1950s — towing signs,” she said. “It does not invite the public to be here. If you’re blocking access to my building, I need you to not be there.”

Her customers, she said, have included Seattle-based icons — the Foo Fighters, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis and ODESZA, among them — and performers on tour like Wynton Marsalis and Elvis Costello.

She said the musicians and their crews rely on the unobstructed access she’s been able to provide to her building. The musical acts often transport thousands of pounds of equipment to and from the rehearsal spaces she rents out, and they can’t do that if parked cars block their path.

Around 2002, when Opitz purchased her building, other sparks of redevelopment were helping to revitalize the once-sleepy SODO into the thriving neighborhood it is today.

Safeco Field opened in 1999 at the neighborhood’s northern edge. Just north of there, the Kingdome was demolished and the modern-day CenturyLink Field was erected in its place three years later. Starbucks moved its global headquarters into the heart of SODO, too, and multiplied its workforce in the process — blossoming from the same economic boom the rest of Seattle experienced.

With the pressure of more people coming in, and more people coming in, and more people coming in, people don’t have the same elbow room they used to have.

DuComb said the city’s hands-off attitude in SODO “helped keep manufacturing and industrial lands cheap.”

“It helped keep jobs and an economic workforce base affordable,” she said. "Parking is affordable — it’s still free.

“But with the pressure of more people coming in, and more people coming in, and more people coming in, people don’t have the same elbow room they used to have.”

The influx of people naturally escalated the demand for parking. Commuters fought for the right to occupy the public rights of way — particularly behind Opitz’s building, which is across First Avenue from Starbucks’ headquarters. After Opitz towed a couple of cars and their owners complained, SDOT in 2006 sent its first warning letter to her. They continued intermittently about every 18 months, she said, until the notice of a daily fine came in 2015.

“We heard complaints [from motorists] of either not being able to access those areas or getting notes on their cars and things like that,” Estey said of SDOT’s efforts in the mid-2000s to step up its parking regulations in SODO.

Although those efforts, in some ways, appear to run counter to other city attempts to promote local business, particularly in Seattle’s arts and music scene, Estey insists SDOT has been accommodating to SODO’s businesses.

But when asked about the continued frustrations SODO property owners told Crosscut they continue to voice to the city, Estey downplayed the existence of the complaints. “I’m not aware of a lot of consternation out there,” he told Crosscut last week. “I feel like we’ve had lot of success, meeting the needs of property owners and installing signs.”

In February 2017, more than 30 SODO businesses — spearheaded by Opitz — co-signed a letter sent to then-Seattle Mayor Ed Murray and Councilmember Bruce Harrell in the hopes of getting the city’s top brass to intervene in the neighborhood’s conflict with SDOT. “SDOT is harming us all and forcing us to consider relocating to other cities,” the business owners wrote.

February 2017 letter from SODO businesses to City Hall

From the city, they received “no response. Crickets,” Opitz said, although she added that Harrell’s office has been “very receptive” in conversations. Current Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan also was apprised of the neighborhood’s problems during a campaign stop last fall before she was elected, SODO business owners said. Her office did not respond to a request for comment.

Tales of confusing signage, inconsistent enforcement

Estey said he couldn’t comment on Opitz’s situation specifically, because her legal fight with the city is still pending on appeal. But he emphasized: “We continue to have a willingness to work with any of the businesses out there with whatever parking signs, restrictions, loading signs that are out there, whatever might fit their needs.”

But business owners tell an opposite story, complaining of a city bureaucracy tone-deaf and insensitive to their needs.

The city has offered a variety of short-term parking and load-only signs to businesses to accommodate their loading zones, which aren’t supposed to be obstructed by public parking.

But the placement of some parking signs in the neighborhood are confusing or even blatantly contradictory. Outside a U-Haul store that abuts Occidental, for example, the business has painted on its loading doors warnings of “no parking” to ensure access, but mere inches away is posted a city sign indicating the area is available for public parking. Only the city sign carries any legal authority.

Several business owners said the signage the city offers isn’t workable and parking rules are sometimes not enforced consistently. They complain, for instance, that commuters or short-term guests park in the loading areas illegally and get no tickets, only to have the businesses' own trucks ticketed by Seattle police if they go over posted time limits during routine deliveries.

“It was always really frustrating that they wouldn’t let us park behind the business,” said Watson, the former manager at Carpet To Go. “If we didn’t keep the ‘no parking’ signs up, anybody would come and park there and park in our doorway, and then the delivery trucks couldn’t get in.”

Wick, whose architectural woodworking business abuts Utah Avenue in the rear, volunteered similar frustrations.

“I’ve been told that the only way I can secure that space [behind my business] is to put a ‘load-zone only’ sign, but then not I’m allowed to park my vans back there at all. They would be subject to tickets, and you never know when they’re going to ticket,” she said.

Wick said her business received “nasty letters” from the city on two occasions: once when the business obstructed its adjacent right of way with large carts to prevent the public from parking there, and another time when they put an orange cone in front of their fire-escape door to prevent parked cars from blocking it for safety reasons.

“In both cases, we tried to be fairly compliant, but now I say, ‘too bad, I’m going to do it anyway,’ ” she said. “We have to be able to access our doors.”

Parked cars pack the rights of way behind O.B. Williams Company off Utah Avenue, south of Holgate Street, in Seattle's SODO neighborhood on Thursday, March 1, 2018. (Photo by Kristen M. Clark/Crosscut)

Enforcing parking laws falls on Seattle Police, not SDOT. Seattle Police Capt. Eric Sano said 10 parking enforcement units are assigned to the southside of the city, including SODO. They “primarily respond to calls for service about vehicles in load-zones” but also engage in “routine proactive enforcement” to ensure neighborhood parking laws are abided by, he said.

But Sano said there’s no exemption in city law that would give businesses a break for parking in public load-only zones outside their own property and that officers “can only enforce those [parking] signs that are posted by the city.”

Two solutions proposed but city says ‘no’

The pressures of growth in SODO aren’t unique from elsewhere in the city, SDOT officials argue, nor is the circumstance that the lot lines for so many SODO businesses end at their doorstep. Businesses in downtown Seattle and in neighborhoods, like Ballard or the International District, face similar constraints with no control of the rights of way outside their doors.

But in SODO, the rail lines on the rights of way historically afforded businesses unobstructed access to their loading docks. That was a benefit the businesses said they enjoyed until the city changed its attitude.

“It used to be really quiet back here,” Wick said. “Then it became widely known ... that the city owns all the land around the building. It’s a free-for-all so anybody can park anywhere anytime.”

We just can’t set the public right of way aside for private use.

Various business owners in SODO have proposed one of two solutions to city officials, both of which could mean a revenue stream for city coffers: Grant businesses an annual street-use permit to use the right of way for their commercial needs, or have the city vacate its claim to the right of way altogether, giving the businesses full control.

“What I have said to SDOT numerous times, this is something that I hear and we would love to see something figured out,” said Erin Goodman, executive director for the SODO Business Improvement Area. The group stays neutral on land-use issues, Goodman said, but it has served as an intermediary in relaying the concerns of SODO landowners to the city.

She noted SDOT has been “very responsive” in developing a new parking plan that mostly addresses First Avenue South. “It’s incremental changes but it’s a win,” she said of that plan, “but on this [right of way] issue, I have not seen a strong willingness.”

Several business owners, including Opitz, favor the idea of a permit but city officials dismiss the possibility.

Estey, the city’s parking manager, said SDOT does not grant street-use permits “for private use. We could grant it on a temporary basis for construction, but on an ongoing basis, to issue a permit for their own exclusive use is not something we would do.”

However, within SODO, there are examples of where that has been done, DuComb noted, adding that she finds the city’s resistance to work with the businesses “so perplexing.”

The building off Hanford that houses the law firm where DuComb now works pays a monthly fee, she said, for a permit to use the public right of way. In that space, the building owner has constructed a permanent stairwell and accessibility ramp out of concrete, for the use by the privately owned building.

Additionally, she noted the city handed over control of a full city-block of Utah Avenue, between South Stacy Street and South Lander Street, to owners of the land that houses Starbucks’ global headquarters.

City records show the Seattle City Council unanimously approved a permit in 2004 that gave up public control of that stretch of Utah for at least 10 years. The council renewed that lease in 2015, relinquishing its ownership of the street for another 10 years and potentially through 2045. The city gets tens of thousands of dollars a year in extra revenue every year — for 2018, the fee is $30,227, SDOT said — in return for Starbucks’ private control of the former street as an outdoor courtyard in front of its headquarters.

DuComb said she favors a similar solution — a “partial street vacation” — for the right of way next to SODO businesses off Occidental and Utah, as something that "gives both sides the most bang for the buck.” A business gets private control of the right of way, and “the city gets a lump of cash from them buying it, and then we have a pot of money to use for SODO infrastructure, for housing and apartments, or whatever we think is the appropriate use,” she said.

SDOT did not respond to follow-up questions inquiring further as to why a street-use permit or partial street vacation couldn’t be considered for the SODO businesses, given the examples DuComb cited.

In the interview with Crosscut, Estey stressed that officials at SDOT “do try to be collaborative with the folks out there to understand their needs. ... We just can’t set the public right of way aside for private use.”

Meanwhile, Opitz continues to fight the city for the right to access her music rehearsal business as she had previously.

A box of paperwork sits in the living room of Seattle Rehearsal owner Jodi Opitz, relating to a lawsuit between her business and the City of Seattle over her non-sanctioned "no parking" signs. Opitz is being fined $500 a day for not having proper parking signage that allows the public to park in the public right of way next to her building. (Photo by Lindsey Wasson for Crosscut)

A Seattle Municipal Court judge ruled in the city’s favor last year and ordered Opitz to pay up on the fine. (The judge’s reason isn’t detailed in the order of summary judgment.) Opitz is appealing that decision in King County Superior Court.

“I refuse to take down my signs,” she said, even as she said her legal bills exceed $200,000 on top of the half-million dollars in fines that the city would still have her pay.

While her case is the most prominent example of resistance, some of her SODO neighbors have tried to work around the city’s firm grip.

Some businesses have spray-painted “no parking” on their loading doors, and one business just down the block from Opitz had towing warnings temporarily posted with duct tape on a recent afternoon. Opitz said she’s seen such businesses take down their signs when they get warnings from the city, only to put them back up a couple weeks later. “I refuse to play that cat-and-mouse game,” she said.

Several of her customers attested in sworn court statements that they would have to stop using Opitz’s facilities if it couldn’t be guaranteed that the building’s loading doors wouldn’t be blocked.

“I cannot risk my bands having unreliable access to Jodi’s rehearsal space,” wrote Rick Marino, a tour manager for various musical acts. “Jodi’s building is the premiere rehearsal studio in Seattle for bands on tour to rehearse in – it is the only rehearsal studio in the Seattle area with the location and facilities to accommodate the needs of touring bands like Bad Religion and The Replacements. Her business is helping rejuvenate that area of Seattle.”

“If Jodi’s rehearsal studio is forced to close because artists and bands can no longer reasonably access her rehearsal studios with their equipment, it would create a void in the Seattle music community,” Joshua Dick, a music manager whose clients include Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, echoed in his own declaration.

For her part, Opitz is holding out hope for an amicable resolution and a viable solution for the neighborhood as a whole.

“SDOT hasn’t come to the conclusion yet that there’s no sign that they can offer that keeps the public out and lets the business owner operate. It doesn’t exist, but they haven’t come to that conclusion yet,” she said. “It’s just such a complex problem, and I can’t get anybody at the top [of City Hall] to address it. … It’s not a survivable event for me.”

Jodi Opitz, owner of Seattle Rehearsal and Sodo Pop, says “it’s not a survivable event” for her business if she is forced to comply with the city's current parking regulations — which say the public should be allowed to park in the right of way immediately behind her building off Occidental Avenue. (Photo by Lindsey Wasson for Crosscut)