For many months, youth across the globe, including here in Seattle, have been striking for our future. “Fridays for Future” is a movement started by Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old activist who, beginning in August 2018, sat in front of the Swedish parliament every school day for three weeks to protest the government’s inaction on climate change. Her actions went viral. Youth fighting climate change all over the world joined the movement #FridaysForFuture.

On Aug. 9, youth climate activists gathered at Seattle City Hall to protest the inaction of our city government and to call attention to our global emergency. They have been successfully organizing these actions for months. But last week’s was special: The Seattle City Council was addressing the Green New Deal, a resolution marking the city’s commitment to fighting climate change through a broad range of green initiatives.

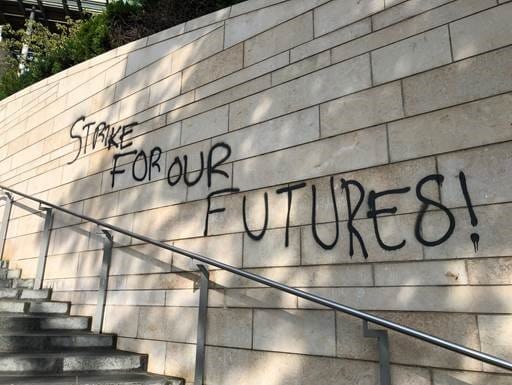

At some point that Friday, another protester present at the action handed a seventh-grade girl a can of what she had been advised was sprayable, washable sidewalk chalk. The youth then wrote “strike for our futures” on a wall outside City Hall. An honest mistake, the spray can, labeled “CHALK,” was actually spray paint intended to create a matte, chalklike finish on surfaces.

Not long after the police arrived responding to an incident of reported vandalism, the youth was attempting to clean up the paint as a crowd explained to SPD the mistake, trying to dissuade them from arresting her. (The young girl confirmed to me that she had looked up on her phone ways to clean the paint, once she realized that's what it was.) The effort proved futile; SPD handcuffed the crying girl and an adult ally, taking the youth to the precinct and booking the adult into King County Jail. The girl was eventually released to her parents.

In response to this incident, I posted on Twitter, “Imagine if instead of arresting this little girl the cops had helped her clean it up. Imagine if they had thanked her for her service for protecting the planet. That kind of public service would have actually been transformative and accountable.” As you can imagine, this prompted a lot of conversation! Why would I say such a thing?

I believe in restorative justice. Restorative justice pursues the restoration of all parties in a situation through accountability and healing engagement. A key part of this approach is accountability — not just on the part of those who caused the most recent harm, but anyone who may have contributed to the events that led to that harm. This often requires whole communities to participate in the remedy and healing process to restore us all back to a trusting relationship with each other. Restorative justice, unlike punitive and retributive justice models, does not view punishment as the preferred method of establishing accountability and encouraging prosocial behavior. In fact, punitive models are often traumatizing and set people up to recidivate, develop resentment and/or experience or cause additional harm.

This particular situation is further complicated by the age of the youth, her intent to use a washable substance — again, an honest mistake — and the fact that these youth activists are bearing the burden of addressing climate change, a dire situation that started long before they were even born, but is impacting their present and may forever alter their future. They are literally fighting for their future lives! And yet many governments and people remain mostly unresponsive to this crisis. How is such inaction accountable? What kind of example are we setting?

Accountability means to accept responsibility, and, in a restorative justice context, to do something to set it right. Justice should not dehumanize, harm or set people up for further failure. Rather, it should teach people how to own their mistakes, correct them and move on to do better by their selves and others. Restorative methods of justice, especially when coupled with prearrest diversion, can limit the traumatic effects of policing, arrest, prosecution and incarceration. These methods are also more likely to aid community members in developing prosocial behaviors like personal responsibility and community connections, which can prevent youth and adults from entering the criminal legal system in the first place.

We’ve all heard the saying, “Hurt people hurt people.” Conversely, “Loved people love people.” Restorative justice aims to heal harm when it has occurred and prevent future harm by ensuring that when accountability is necessary the process leaves everyone, including those who cause harm, better off mentally, emotionally, physically and spiritually. In order for restorative justice to become a reality, we need to change the way we think about the role of police, law and justice. Restorative justice needs to permeate all we do, from our justice system to our housing policies, schools, budgeting and activism.

To challenge my logic, someone on Twitter posed a hypothetical: If a 13-year old youth at a MAGA rally spray-painted “Make America Great Again” on Seattle City Hall, should they receive the same restorative justice response? My answer is an emphatic “yes.” All youth deserve restorative justice. Not to mention that any youth tagging City Hall with “Make America Great Again” has learned that from “us,” the larger society. We are responsible for the hate rhetoric taking over this country, and just as with climate change, we have the responsibility of challenging the rising tide of hate and hate speech until it recedes. We must do so without further traumatizing and dehumanizing children caught in the wake.

So imagine if instead of arresting this little girl the cops had helped her clean it up. Imagine if they had thanked her for her service for protecting the planet. That kind of public service would have actually been transformative and accountable. That kind of public service would change our public conversation about justice for the betterment of us all.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that the seventh-grade girl wrote “Strike for our futures” and another symbol on a wall outside City Hall. The other symbol was made by someone else. The story has been corrected.