Alice Gosti came to Seattle from Italy with a dream: She wanted to be a choreographer. “I left my home, I left my friends, I left everyone I love,” Gosti says. “I was all in.”

Gosti enrolled at the University of Washington in 2004, but her education transcended the classroom. Seattle offered a cornucopia of dance, and Gosti sampled everything — from musical theater to classical ballet to modern work by a bevy of local choreographers. And she wasted no time when it came to making her own dances; she applied for grants and artist residencies, showing work everywhere from small theaters to St. Mark’s Cathedral on Capitol Hill.

Eighteen years after she arrived in the Pacific Northwest, Gosti now heads her own Seattle-based performance troupe, Malacarne. Talent and perseverance aside, she knows that her success is due in no small measure to landing in Seattle at the right time. She worries that aspiring dancemakers arriving today might not be so lucky.

“We live in a city with a really high cost of living,” Gosti says. “And we really don’t support the arts.”

The lack of support manifests in a dearth of affordable studio space, limited funding and fewer platforms for emerging artists to perform.

It’s an about-face for a city that has nurtured Western dance traditions for more than 100 years.

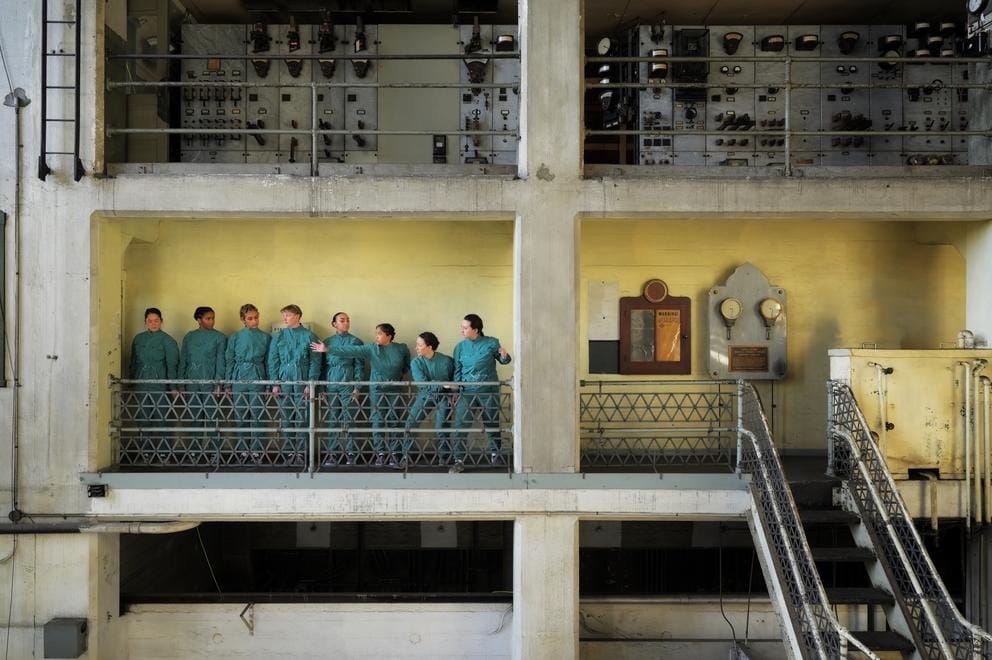

Alice Gosti's dance company Malacarne performing inside the Georgetown Steam Plant in April, 2022. (Joe Iano)

In the late 19th century, decades before Nellie Cornish founded the art school that bears her name, Seattle’s grand dames — descendants of such early white settlers as the Dennys and the Blaines — hosted touring musicians, thespians and dancers in their salons. By 1916, Cornish’s school, originally founded as the Cornish School of Music, had added a dance department; in the late 1930s, it served as the launching pad for a Centralia native who became an internationally acclaimed choreographer: Merce Cunningham. Decades later, another dance luminary, Seattle native Mark Morris, got his early training here.

Although both Cunningham and Morris built their careers outside the Northwest, other choreographers soon swept in. Emerging artists learned they could find affordable space in this historically blue-collar city, and Seattle was far enough from art world capitals like New York, Tokyo and Berlin that it gave artists the chance to try — and fail — outside of the glaring spotlight.

Bill Evans relocated his eponymous dance company from Salt Lake City to Seattle in 1976. His dancers included such emerging choreographers as Shirley Jenkins, Wade Madsen and Llory Wilson. And Evans held regular summer dance workshops, attracting students from around the country. They met other local artists, forged collaborations, formed dance companies. To misquote an old movie, they built it, and dancers came.

“I moved up here because I knew there was a choreography scene,” says choreographer Pat Graney, who arrived in 1979. A decade later, Graney had established both a national reputation and her own dance company, hiring dancers from around the country, including New Yorkers KT Niehoff and Michele Miller. That duo founded Velocity Dance Center in 1996, which, in turn, developed into another magnet for aspiring dancemakers. Along with the Cornish and UW dance programs, plus Pacific Northwest Ballet and Spectrum Dance Theatre, they turned 1990s Seattle into a dance mecca.

These days, Seattle attracts very different newcomers: legions of highly paid young professionals lured by jobs with Amazon, Microsoft and other tech companies. And the city has started to remake itself to accommodate them. New luxury developments are replacing older buildings that once offered low-cost housing, studio and rehearsal space for artists. Small theaters and clubs have faced rent hikes, even eviction, from landlords and new developers. (Early on in this trend, several arts organizations, including Velocity Dance Center, had to leave their former digs in Odd Fellows Hall.)

The tenuous financial situation got even worse when the pandemic hit in March 2020. Performance venues abruptly closed in an attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19, throwing thousands of local artists out of work overnight and jeopardizing the presenting organizations themselves.

Sruti Desai (left) and Cheryl Delostrinos in Pat Graney’s 'Girl Gods,' which was presented at On the Boards in Seattle in 2015. (Jenny May Peterson)

Even as pandemic restrictions ease and theaters and clubs start to re-open, choreographers like Graney, Gosti and many others are struggling to stay in Seattle. Graney charges that nobody at City Hall, or anywhere outside the dance community itself, seems concerned that artists are being priced out of the city. “There’s no one at the helm who has an interest in dance,” Graney maintains. “People don’t care, they just don’t care.”

Beyond affordability, many local dance artists and their audiences believe that the developmental ladder for aspiring choreographers once centered at On the Boards, the acclaimed local contemporary performance presenter, has disappeared.

Over its 42-year history On the Boards offered a number of incubator programs, including Choreography Etcetera and the long-running 12 Minutes Max, which presented short works by selected artists, giving them an opportunity to perform in front of a live audience. Another On the Boards program, Northwest New Works, presented longer, often more polished, work by regional performers. These programs served as steppingstones to On the Boards’ mainstage.

Choreography Etcetera is long gone; On the Boards no longer produces either Northwest New Works or 12 Minutes Max. Seattle-based dance writer Sandra Kurtz acknowledges that On the Boards has evolved over the years, but she believes the developmental programs were one of the organization’s biggest strengths. “There was the intention that they were a nurturing space, as well as bringing in big names,” she says.

On the Boards Artistic Director Rachel Cook says the organization is currently focused on presenting and producing “the best of global contemporary performance” in “the blurry category of theater, dance, performance art, sound and more” — whether the works are created locally or not.

She points to two dance artists with Seattle connections on On the Boards’ schedule next season: Zoe Scofield (a former Seattleite) and her company Zoe/Juniper, and Heather Kravas. Still, many observers I spoke with worry that On the Boards’ suspension of its developmental programs impacts the vitality of Seattle’s contemporary dance scene.

“It used to feel much more like there was an ecosystem of opportunities,” says Dayna Hanson, co-founder of Base, the small presenter that took over production of 12 Minutes Max in 2018. Hanson has been making dance and multimedia art in Seattle since 1987, initially as part of the internationally recognized group 33 Fainting Spells.

In 2016 she and two partners, artists Peggy Piacenza (a former member of Pat Graney’s company) and Dave Proscia, leased a small theater at the artists’ enclave Equinox in Georgetown. In part, they wanted to use Base to make their own work. But from the get-go, Base has offered other contemporary artists money, time and affordable space in which to create — all much harder to come by in 2022 than when the Base co-founders came onto the Seattle scene.

“We wanted a place where you could feel the pressure was lifted,” Hanson says, “letting people have that experience we had, that it’s manageable to be an artist and have a part-time job and not be in constant stress.”

Members of Seattle dance company Whim W'Him in rehearsal for a new show running May 13-21, 2022, at Cornish Playhouse. Director Olivier Wevers says he's had to do significant belt-tightening to keep the small company afloat. (Jim Coleman)

Although they’re happy to present 12 Minutes Max at Base, neither Hanson nor Piacenza believes their small theater can fill the role that On the Boards once played for emerging artists. “It wasn’t guaranteed that you’d have a show on the mainstage there,” says Piacenza, “but even having some low level of presentation, people could learn about you, and then you’d start building an audience. I wish there were more venues that could support younger artists these days.”

One such venue, Velocity Dance Center, has spent much of the pandemic on life support. (It was facing financial trouble even before COVID-19 hit.) When the venue’s Capitol Hill landlords raised the rent on the home Velocity had occupied for the past decade, the struggling nonprofit managed to get out of its lease. Since then, Velocity has patched together a roster of temporary spaces to hold both classes and performances, partnering with venues around the city, including Base, which now co-presents Velocity’s Bridge Project, a platform for emerging creators.

“We passionately wanted to keep focusing on residencies, especially when things really slowed down during the pandemic,” says Velocity Artistic Director Fox Whitney. “We did whatever work we could to make sure artists could access resources and space.”

A federal relief loan served as a lifeline for the cash-strapped organization. In March of this year, Velocity signed a three-year agreement to share space at the 12th Avenue Arts multi-theater space, just across the street from its old home. Although Velocity’s summer residency program and related performances will take place there, Executive Director Erin Johnson says the organization will continue the hunt for a permanent home.

Other small Seattle dance companies also relied on federal and local relief funds to make it through the pandemic. They’re producing live shows again, but often to smaller audiences — in part because they’re trying to maintain distance between patrons, but also because former ticket buyers have been slow to come back to in-person performances. And, with the uncertainty about what lies ahead when it comes to COVID-19, they’re leery about the future.

“The sense of urgency has waned as the pandemic lingered, and so has the financial support,” says Cyrus Khambatta, artistic director of Khambatta Dance. “Many dance troupes feel like they’re starting all over. Again!”

Olivier Wevers, artistic director of Whim W’Him, has managed to maintain dancer contracts and health benefits through the pandemic, but not without significant belt-tightening. He says city leaders and the general public don’t really understand the financial hit Seattle artists have sustained over the past two years. “The city used to be considered an artistic hub,” Wevers says. “Now I think we’ve slid very low.”

Nia-Amina Minor in Seattle choreographer Amanda Morgan's "Musings," created for Seattle Dance Collective in 2020. (Seattle Dance Collective)

Not every dance artist is invested in the health of established companies and institutions. Dancer and creative professional David Rue says that, historically, these groups haven’t been particularly welcoming to BIPOC artists like himself.

He looks to other avenues — house parties, nightclubs, even local galleries — to see work by like-minded artists of color. “There are so many spaces in Seattle that are Black spaces, where Black and brown people show up without the baggage that comes with the [white] institutions,” Rue says. “People are not going to wait for those institutions to come around, because we have options that let us come together and celebrate who we are.”

In the two years since George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officers, Rue has watched organizations like Base, Velocity and On the Boards open doors and opportunities to more BIPOC artists, but he’s skeptical the changes will last long.

Choreographer and performer Nia-Amina Minor, currently working on a Velocity commission honoring Seattle’s Black dance history, concurs. She’s waiting to see if the move for diversity and inclusivity is more than a passing trend. “I think the main point is sustainability,” Minor says. “We’re having the difficult conversation of what it means to accept an opportunity that reflects an immediate response to a demand for change.”

Despite their misgivings, Minor and Rue are excited by the breadth of dance the city has to offer, everything from hip-hop to ballet to burlesque, sometimes all in a single performance. Rue points to Amanda Morgan, a young Black artist with a foot in two dance worlds. By day, she’s a Pacific Northwest Ballet company member, but 2½ years ago, Morgan started a multimedia contemporary arts enterprise called Seattle Project.

“I wanted to give more visibility to BIPOC and queer artists,” Morgan said in late March, before a rehearsal for Seattle Project’s most recent show, truth be told, a mix of live dance and dance films. She wanted a platform to experiment with artistic boundaries. And she’s not afraid to fail. “At the end of the day, at least I tried stuff, at least I used my voice,” Morgan says.

To Rue, Morgan is an exemplar of how young artists can pursue their vision in this city, raising their own money and self-producing performances in nontraditional venues. But he still sees a need for a dance community hub, a place to take classes, to network and share information about everything from grants to potential collaborators. Right now, what Rue calls a “plethora of inspirational artists” seem to be working in disconnected silos. “These people are doing amazing stuff,” Rue explains, “but they don’t talk to each other. They have this mentality of ‘we do this over here, you do that over there.’”

Newly housed in the former home of Velocity Dance Center, the relocated and revamped eXit Space will host dance classes and performances. (Daniel Spils)

Marlo Martin has been thinking deeply about how to bridge these chasms. A longtime choreographer and dance producer, Martin runs eXit Space Dance, a for-profit enterprise that includes classes and performance spaces at various Seattle venues. Last year, she took over Velocity Dance Center’s lease. She renovated the small theater, adding new seating, lights and a lounge.

Martin hopes to present a wide variety of dance in the renamed Nod Theater, but she’s dreaming beyond the shows themselves, planning everything from a new artist residency program to production workshops to a contemporary dance trade fair, where local choreographers and dance companies could mingle. “There needs to be a willingness to take a risk,” she says. “If we all just take one step forward!”

Martin, Minor, and many other local dance artists say it’s time to move beyond what they call a “scarcity mentality,” which has led to squabbling over limited public grants and performance opportunities. Dance writer Kurtz points out that when the pandemic shut down live performance, dancers began to create work on video, finding new audiences in Seattle and around the globe. Kurtz believes artists will dip into that same well of creativity to reimagine how to realize their artistic visions, whether that means funding, presentation, even the notion of live performance itself.

“We’re in a paradigm shift,” she maintains. Despite the challenges, Kurtz and others think the future of Seattle’s contemporary dance scene may look different from its past, but it will persist.

“If you’re an artist, you’re gonna be an artist, no matter what the situation is,” insists Base co-founder Peggy Piacenza. “Whether you make a show in your bedroom, on the streets or in a theater, you’re gonna keep making work. I’m an artist, and I haven’t given up on that.”