How the future of women in the workplace was shaped in Puget Sound

How the future of women in the workplace was shaped in Puget Sound

After Pearl Harbor, the United States went to war, and Seattle became a total blackout town – no lights anywhere at night. Spotters scanned the skies and scoured the waters of Puget Sound, looking for Japanese war planes and submarines. People of Japanese descent were sent to internment camps inland. Soon, everything became scarce, from butter to sugar to cloth.

And Seattle’s industries mobilized to produce the machines of war, with women leading the charge to build them.

Following the United States’ entrance into the war in 1941, the Seattle area’s population increased more than 50 percent in four years, as Boeing and the shipyards recruited workers across the nation. As men went into uniform, women took their places at these companies.

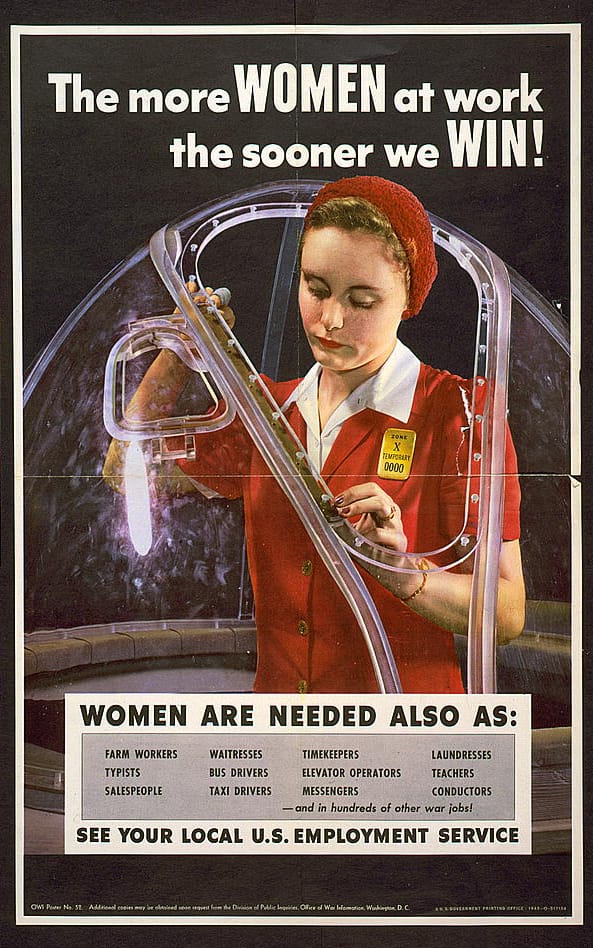

Of Boeing’s 50,000 wartime workers in Seattle, more than half were women, and about 10% of those women were African-American. The face of Seattle industry changed dramatically, as “Rosie the Riveter”, “Wanda the Welder”, and “Elsie the Electrician” went to work, taking a prominent place in what was once a man’s world. They learned industrial skills, earned enough money to pay their own way, and forever changed the role women play in the workforce.

But rather than write about these women, I’d prefer to let them speak for themselves. Boeing began as Pacific Aero Products exactly a hundred years ago in Seattle. As part of the centennial celebration of the company, we present an oral history of the women who kept the B-17s and B-29s coming on the World War II homefront, through recordings held in the Museum of History & Industry archives.

As the war began, on Sunday, December 7, 1941….

I was down at my mother-in-law’s, doing our laundry. I remember my husband was outside washing the car. Then I heard it on the radio - that Pearl Harbor had been bombed- and I ran out to tell him. He said, “Oh, we’ll lick them in two weeks.” -Edith Robertson

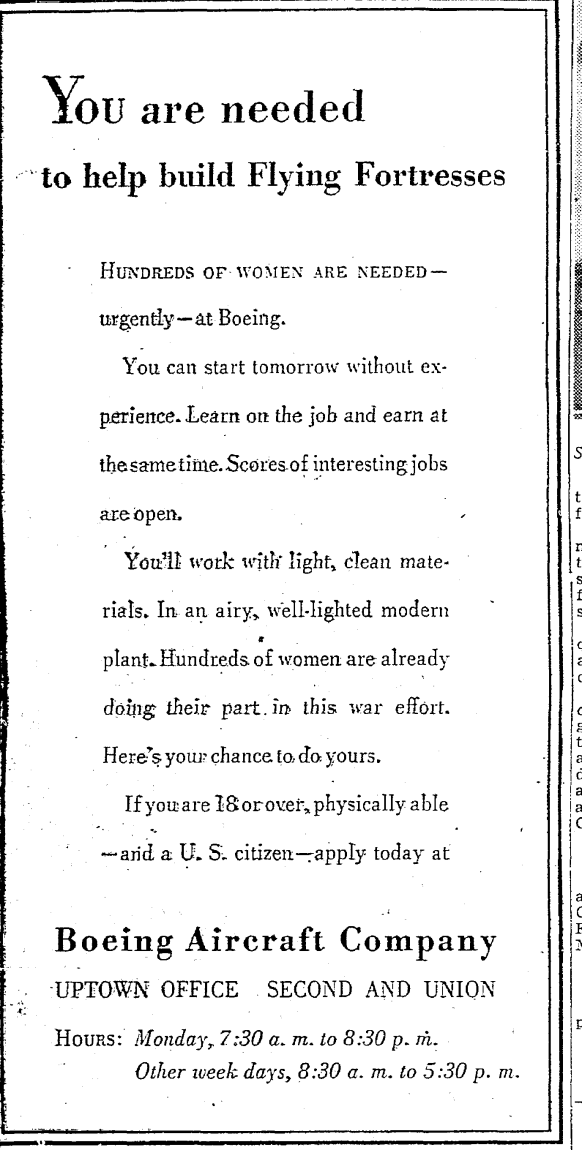

One day, there was a big splash in the Seattle papers. Boeing would be interviewing for women workers, no experience necessary. I went right to work at the end of that week in the tool room. The head superintendent said that he’d never heard of such a thing as putting women in factories, and it was certainly not going to work. He said, “The happiest day of my life will be when Boeing decides that they can’t use these women, and I can be there personally to kick them out the door!” -Inez Sauer

As local men went off to war, leaving their jobs behind, recruiters fanned out throughout the United States, encouraging willing women from the city and the country to come west, to Seattle.

The women war workers came from all walks of life. There were an awful lot of them from North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota. Some were housewives and some were young girls. There were quite a few, especially on the day shift, whose husbands or boyfriends were in the service and they were working here in Seattle. -Edith Robertson

In one month, we took applications from war workers from 38 states. These were the war workers, recruited to Seattle – to Boeing and the shipyards. We had people from everywhere – from Montana and Idaho and Minnesota, and a number from different states in the South. -Doris Eason

I was awfully bashful, and being fresh out of the country, I didn’t know city ways at all. When I got into the engineering department, I was in the flight test steno pool. The ladies’ restroom was clear across the whole engineering building. So I had to walk in front of all those engineers. And, of course, they all whistled and made comments and oh, that was so embarrassing to me. They loved to see me blush and they just kept it up, you know. -Elsie Anderson

Like all the new female recruits who joined the “soldiers of production,” black "Rosies" left their homes, came to Seattle, learned their trade and went to work. But being black shaped their wartime experiences.

Some Montana women didn’t want to work with me at Boeing because I was black. One of them said that I had a tail, you know, “black folks have tails.” And so Josephine Ryman - I never forget that lady – she said you ain’t going to talk to that girl like that! She said, I got a daughter and she is her age and I’m going to be her mama. And they didn’t never bother me anymore. -Vivian Laye

Sometimes, we black women had to do the menial jobs. If I was on a riveting job or and some cleanup needed to be done, I would have to relinquish my work and go do the clean up where another white lady would go over and do my job while I got the plane cleaned or floor swept or something like that. -Katherine Thompkins

As a black woman, I felt like we were all just about the same because they wanted to get those airplanes out. By being a young person, I could work fast. So when you worked fast and kept up with your work you had no problems with the supervisors. -Katie Burks

At Boeing, on the B-17 assembly line, we spent only forty-nine minutes at each position at peak rate, including inspection of all completed jobs. Forty-nine minutes! … And before the war, they said it had taken as long as eight hours spent on each terminal! We women worked so hard – we felt we had something to prove. -Katherine Thompkins

On the wartime homefront, Boeing and the shipyards ran three shifts a day and metro Seattle turned into a round-the-clock city. But the shortages, worries and injustice of war changed everyday life for everyone.

Most of the boys in my high school class went in the service. Some were killed. The man that I had hoped to marry was killed. I was afraid to fall in love. I was afraid that whoever I loved … would die. -Dorothy Elliott

You couldn’t get silk stockings, so they had a cream we could buy. And we used that on our legs so that they’d make them brown, and even sometimes even make the stripe in the back. It was like the seam on a stocking. But if you got your legs against anything, sometimes you’d rub your stockings off [laughing] because it was only makeup. -Betty Parks

One guy I worked with in the shipyard said to me, “You’re working overtime all the time, when do you find time for love?” I says to him, “Oh, you can always find time for that!” -Donna Bajocich

The women who became “soldiers of production” in Seattle trained and learned their jobs. Working side by side with men who were unfit to enter the service or whose jobs were classified, "Rosies" met varied experiences out on the factory floor.

Women were constantly teased on the job. Men were jealous of women but at the same time, they liked them because they could flirt around on the job. You have to be pretty strong to use the riveting gun all day. I could do that – I was the real-life Rosie the Riveter. -Donna Bajocich

With most of the men it was aIl right. But there was a few - there was jealousy – you could tell that. I never thought men gossiped until I got in there - they’re worse than women! They were a little bit jealous if you got a job that they thought they should have. Especially when we got repair work – we earned more money for that. We got $1.34 an hour. If the women got that and the men didn’t, you could tell there was jealousy. -Edith Robertson

I first started at Todd Shipyards, as a sheet metal helper. We were the first women they had on the graveyard shift and it seems to me like there were about ten of us. So the men could all choose who they wanted as their helper. This one man said, “I’ll take Pinky,” meaning me, because I had red hair, I guess. And that was all I was ever known by in there. -Edith Robertson

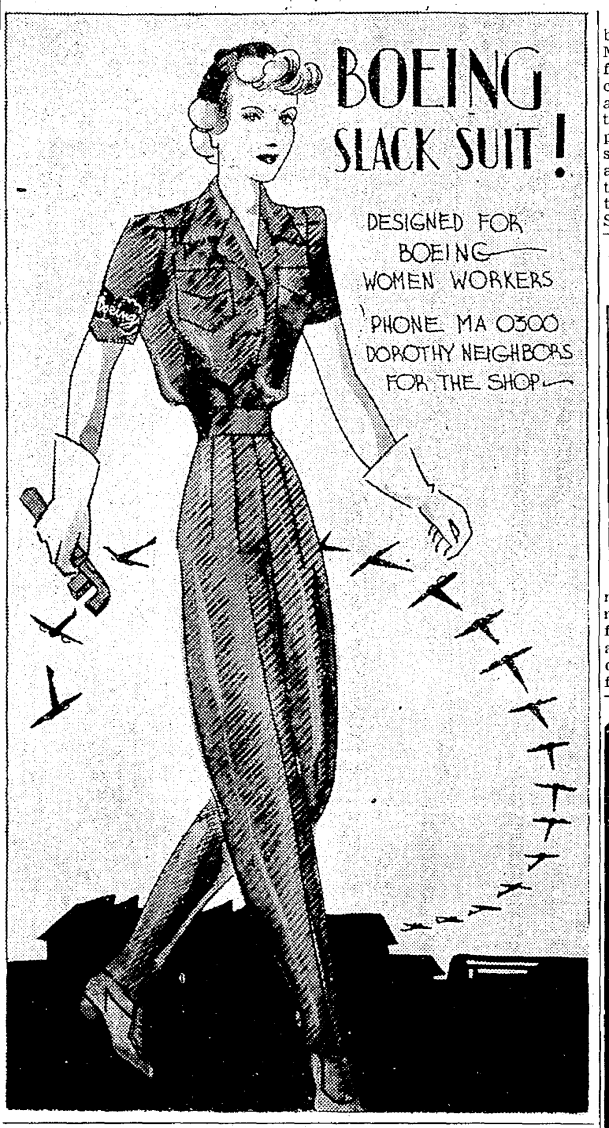

Very few women wore slacks before the war. Once the war came, then it began to be accepted. You had to dress like that, to be safe in the factory. I wore my hair up all the time, in a bandanna, to keep it out of the machinery. -Mora Gilley

I got my hair caught in the drill. But I had my bandanna on like I was supposed to, and it wound around the bandanna as well as my hair. And it took out a patch about a half-inch wide and maybe a couple of inches long. I had to go over to First Aid, and the foreman

from the safety department quizzed me.

“Well, were you wearing a bandana?”

I said, “Yes.”

“Well, how were you wearing it?”

I said, “Just like I have it on right now.”

“Well, can’t see where you were negligent or anything.”

It was just one of those things. -Margaret Berry

He and I were the best rivet team in the whole group, because we worked well together. When they finished the B-17s, I worked on the last one and then they brought in the wing panels of the B-29. -Margaret Berry

Seattle "Rosies" were proud of their role in helping to manufacture the weapons that would win the war.

Boeing production went through the roof during the war – we couldn’t hire and train enough workers! We got to the rate of fourteen B-17s a day here at Boeing Plant 2; the B-29s got up to six a day in Renton. We were putting out a lot of airplanes, and half of the workforce was women. Fully 10% were black. This was unheard of, until World War II. -Howard Hurst

I was very proud to be there, to be a Rosie. I felt like I was doing my part and we all felt that way. It was a very serious business. The war began a major change on how women were seen, and how they saw themselves. -Anne Wells

At the war’s end, when men returned from the frontlines, most women left American factories going home or going back to their old pink-collar jobs as hairdressers or waitresses. Some women bitterly resented this treatment, while others settled down in suburban households to raise families.

But they didn’t forget the independence they had enjoyed on the homefront, and many later became advocates for what was loosely termed “women’s liberation.” The war changed everything, - people, dreams and expectations. And in Seattle, it changed the future of working women in America.

--

Lorraine McConaghy is the Public Historian Emeritus at the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle. Comments? Suggestions for future entries in this series? Contact the author via editor@crosscut.com.

Photo credits:

Title photo of women making a plane + African-American women posed in front of plane: Boeing Company

Lockheed welders: Museum of History and Industry

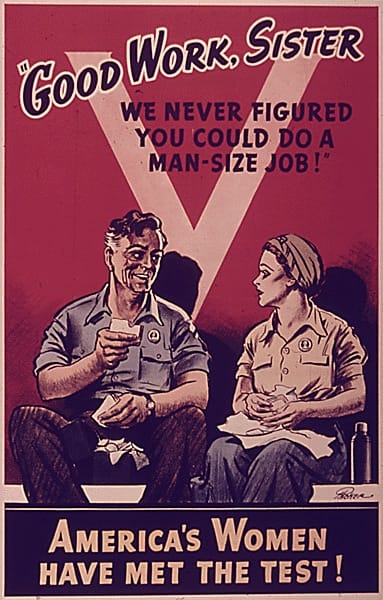

“Good Job Sister” poster: National Archives

Boeing advertisement and slack suit picture: Seattle Times

“Do the Job” poster: U.S. Government Printing Office

“The More Women at Work” poster: U.S. Library of Congress