When Stephanie Anne Johnson was on Season 5 of The Voice in 2013, the singer/songwriter knew exactly what they’d do with the $100,000 if they won the competition. “If I win this thing, I’m gonna pay off my grandmother’s house,” they said in an interview recorded for the show.

Ten years later, Johnson has released “Can’t Go Home,” a song about how their grandmother had to give up the family home in Tacoma. In the very first lines, the story emerges:

Cleaning out the old homestead

Nana can't afford the mortgage

Alone

You can't go home

Born and raised in Tacoma, Johnson grew up singing in front of audiences — including as a preteen at open mics — and studied classical voice throughout high school and college.

This interview is part of our Summer Artist Talks. Read more artist Q&As in the series.

It was later, while working as a lounge singer on cruise ships, that they were inspired to try out for The Voice. Watching former Stadium High School classmate Vicci Martinez place third in Season 1, Johnson recalled in a 2013 Voice interview, “I was like, if that girl can be on TV, I can be on TV!”

Judges Christina Aguilera and Cee Lo Green were impressed with Johnson’s vocals, which at times recalled the classic sound of Aretha Franklin. Despite excelling in soul and country performances, Johnson didn’t win. (After making it to the top 20, they were eliminated in the live playoffs.) But upon returning to Tacoma, they’d made a name for themselves as a versatile vocalist ready to try anything.

The summer before their appearance on The Voice, Johnson had released their first album Hollatchagurl, an eclectic record that dabbles in genres from soul to indie to Americana. The follow-up came six years later, in 2019, with backing band the Hidogs. Called Take This Love, it’s an album filled with Americana twang, the homespun sound of a pedal steel guitar and love songs — all of which reflect Johnson’s lifelong appreciation for country music.

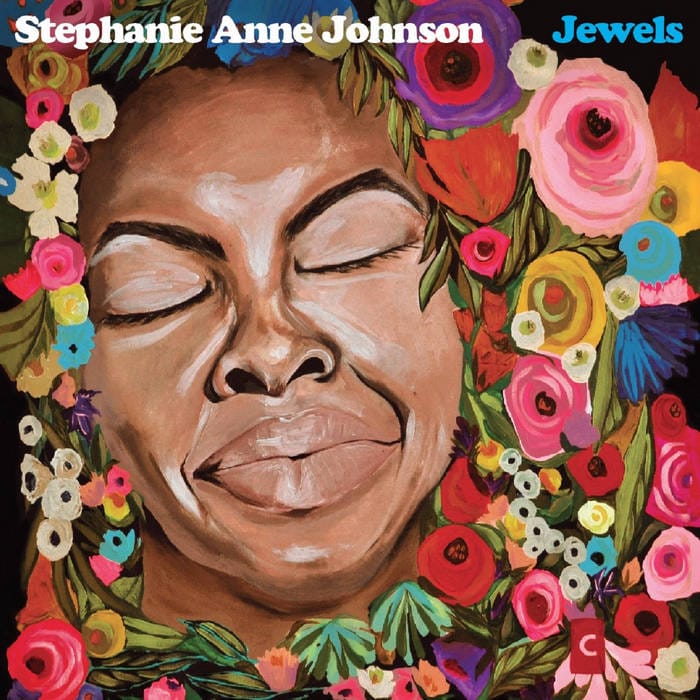

This past April, Johnson released Jewels, a soft, lightly produced record that includes romantic ballads, a mournful apology for alcohol addiction and a compassionate cover of a classical hymn, which is also the title track. The common thread is an organic sound that allows Johnson’s crooning voice and highly personal lyrics to take center stage.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Your new album Jewels is the first solo album you’ve released since 2013. How has your approach to songwriting changed over the past 10 years?

I used to write a lot of love songs — I still love love songs. There’s some great ones on this record. But I started thinking about, “What are the other kinds of love besides romantic love?”

Because we love ourselves, hopefully. We love our families, we love our elders, we love our schools, we love the Earth. And when we love and care for these things, these things flourish — and isn’t that beautiful?

So how do I write songs that people can see themselves in, whether they’re in love or not? That’s been something I’ve been fooling around with for about 10 years, but I feel like I have gotten pretty good at it with this record.

Tacoma and Seattle aren’t cities particularly known for country music. How did you arrive at the genre?

I feel like the country streak in me has been coming since childhood.

My mom was really into Willie Nelson when we were kids, so it was a lot of “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” My brother was very into Duke Ellington, my mother very into James Brown. My grandmother, Bobby “Blue” Bland is her favorite. And then my Grandpa Jack introduced me to ’50s rock, Del Shannon.

I had a beautiful musical landscape in my house, and then I studied classical voice. But as I started meeting other people that play guitar and other songwriters, that's where I found country music. Country music is just soul music for white people.

Maybe it’s because I have a wild imagination, but I’m always — no matter what I'm listening to — looking at the music and imagining myself in it.

I also see the overlap between things like the Great American Songbook jazz standards and classic country. I see the overlap between artists like Billie Holiday and Patsy Cline. [They’re] both doing the same thing — telling a story and trying to get the people to have a drink and a conversation about it.

When you’re writing a song, what comes first for you — the music or the lyrics?

For me, it's always the feeling first. What feelings am I having and then what story am I telling about these feelings?

With “Can’t Go Home” [on Jewels], one of the things I didn’t realize until the song was out was that I'm having a conversation with my brother who died about 20 years ago. The whole song is me just talking to him. So it’s definitely the feeling that happens first.

Then I imagine, where would this song be playing? If this song was in an indie movie, what would the shot list look like? What scene are we in? Who is the speaker? I love to ask myself those questions.

I remember I had a little bit of writer’s block a couple of years ago, and I went to see this poet named Naa Akua. They said to me: “You’re always just telling a story. Beginning, middle and end.” Whether you’re writing a poem or you’re writing some kind of folk, country or blues tune, it’s always just beginning, middle and end. That’s one of the things I love about Americana.

What is one of your most memorable performances?

I want to say it was 2017. I’m doing Aretha Franklin’s version of “The Weight” at the Neptune Theatre with a group that does a tribute to [music documentary] The Last Waltz every year. I kind of blacked out during the performance.

I was looking up in the air and people were loud and it was kind of deafening and I could see the atoms splitting in the air. I thought that was the experience [that] only I was having and then the write-up came out, and the person writing the write-ups had exactly the same [experience].

When I’m making music, not only am I in connection with my body and what I’ve trained it to do for the last 20 years, not only am I in conversation with the musicians on stage, not only am I in conversation with the divine, but I’m also in conversation with everybody else who’s here.

Energetically, that is a lot. I’m very grateful for those feverish states, where it feels OK to be in touch with all those things.

One of the songs on Jewels, “The Day That You Begin,” was written as part of the STYLE program, in which you wrote a song based on a children’s book and then taught students how to write and record their own songs. Why is teaching kids about music important to you?

I love to tell young people that being a musician is a job that you can have. It is not imaginary, it’s not fake, it’s not pretend. The larger culture tells us that being a person who sings or dances or writes the music isn’t important or isn’t real. I love to counteract that.

I went to school at a time [the 1990s and early 2000s] where we still had music class, and we still had choir and there was band and orchestra. … Over the years, the money for music education, which is social emotional learning, is dwindling. If we don’t have music education for young people, and we also don’t have places for young musicians to cut their teeth, where is the music expected to come from?

We have these huge school stadiums where we can watch all kinds of sporting events and pay $15 for a single hot dog, but how better could that money be spent on our young people and making sure they have the equipment they need to express themselves?

How do you feel now that Jewels is out in the world?

I got to sit with this record for six months before it got out. It was a little crazy to not be a busy bee, moving, working all the time, but it was also nice to let that record finish cooking.

When you’re putting something in the oven or you’re doing something on the stovetop, sure, you remove it from the heat, but it’s still cooking as it is cooling down. I feel like a record is that same thing. So I’m curious to see what it will continue to morph into.