When Alice Lord arrived to Seattle from New York around 1892, she and her husband were joining the flood of newcomers drawn to the western boomtown. In the years to come, the Gold Rush would put Seattle on a wave that lasted a decade, as more than 100,000 would-be miners coursed through the city, outfitting themselves, buying meals, hotel rooms, and their passage north. Lord would hold one of the many jobs benefiting from this golden wave, waiting tables at a downtown restaurant.

Waitresses were usually unskilled and single at the time, their “pink-collar” job seen as just one step up from domestic service. Like many of the city’s female typists, store clerks, laundry workers, and more, the waitresses were newcomers far from home, drawn from farms and villages to the bright lights of the big city. Most elite restaurants employed male waiters, and waitresses tended to work in second and third tier eateries. To keep their jobs they did what they were told, walking endlessly, fetching, and often being called to wash dishes and mop floors.

In general, middle-class society regarded waitresses with suspicion – after all, these women were usually single, serving meals to dozens of strangers each day and coming home alone at all hours of the night. Even if the waitress wasn’t a woman of easy virtue or a prostitute, no respectable girl of a good Seattle family would risk the appearance of immorality in that way.

A single waitress, a woman on her own, could not stand up against the authority of her boss and the censure of her community at the time.

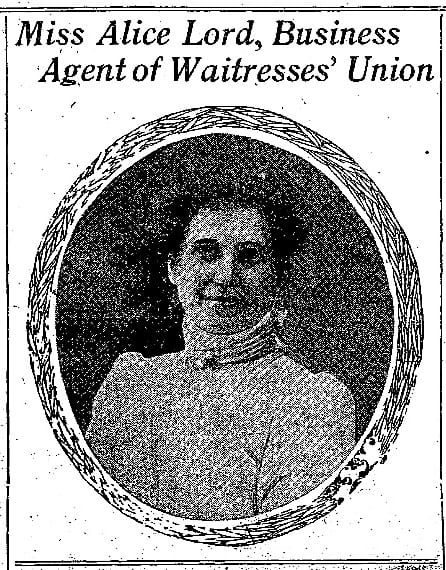

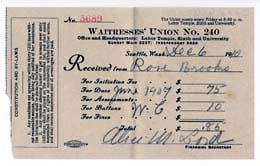

Alice Lord changed that. In March 1900, Lord and 64 other local women founded Waitresses’ Union, Local 240, one of the earliest women’s unions to gain their charter from the national American Federation of Labor (AFL). Lord was elected president shortly thereafter, and represented the city’s waitresses as union president or business agent for nearly 40 years. And in turn, she became one of Seattle’s most prominent advocates for women’s rights, working to improve conditions at home, in the factories, and especially in Seattle’s restaurants.

Members of the Waitresses Union Local 240, in a Labor Day parade circa 1905.

--

The fights Lord waged came on many fronts. There was the issue of wages, for example. At the time, waitresses in the city worked a twelve-hour day for a weekly wage of $5 or $6 – half the wage paid to an unskilled male laborer at local shipyards or factories – and worked seven days a week. Lord tartly pointed out that even horses received one day of rest per week. Her union flexed their muscles, organizing a strike against restaurants that hired non-union waitresses and paid them poorly.

During the fight, Lord herself entered a restaurant staffed with non-union labor, recruited five waitresses to the union on the spot, then returned the next day during the lunch rush and demanded that they walk out, leaving customers unfed at their tables. The owner complained to a reporter that Lord didn’t play fair, and that she pursued a policy of “rule or ruin.”

But she had demonstrated that the union could support waitresses on strike, and withhold their labor until working conditions improved. Through these tactics, Seattle’s waitress union turned 95 percent of the city’s restaurants into closed shops. On the front page of the Seattle Times, on December 8, 1907, Alice Lord declared victory over the “greedy restaurant owners,” saying that “We have met the enemy and he is ours.”

To organize, women working as waitresses needed to perceive themselves differently – that they were more than temporary workers, unmarried and unskilled, incapable of organization. Lord helped them to see themselves as competent and capable, women who could join together to support one another, to power the “union with grit.” The wage fight showed these women they could win.

Then there was the treatment of waitresses by Seattle’s police officers and civilian members of the local so-called Purity Squad. Waitresses returning home at the end of night shifts were often questioned closely by the police – What was their name? Their age? Where did they work? Where did they live? Why were they walking alone?

The clear implication was these women were prostitutes, walking the nighttime streets hunting for customers. In some cases, the police officer insisted on accompanying the woman back to the restaurant to verify her employment, or to her home, to verify her character with the landlord.

Embarrassed and angry, a widowed single mother who worked at a downtown oyster house testified before the Seattle City Council that the police humiliated and intimidated her. She remarked, “I have gone home from my work at 1 o’clock each morning for many months, but not until last week was I insulted when homeward bound and it remained for an officer of the law to commit the offense.”

Alice Lord took up her case before the Council, arguing that working women should be able to commute to and from their homes and places of work at the end of their shift, without harassment.

Alice Lord in her desk in the Waitresses Association of Seattle offices. The union's banner hangs over a piano to the left.

--

Lord eventually became the only woman usually mentioned in newspaper coverage of the area’s labor leadership; she was certainly the best known. Appointed sergeant at arms of Seattle’s Central Labor Council, and then elected vice president in 1905 for several successive terms, Lord participated in every Washington State Federation of Labor convention starting in 1903, well into the 1920s, often giving the benediction at the conclusion of a meeting. She also served as secretary on the board of the local Union of Hoboes, and worked at their homeless shelter.

Her principal focus, however, was always on waitresses, and bettering their working conditions and compensation. This included giving them an eight-hour day, a six-day workweek and a minimum wage. In her advocacy, she eventually galvanized women across the state to push for these issues.

In 1907, Seattle’s Woman’s Century Club recommended passage of the eight-hour day for women, and brought the matter before the city’s Federation of Women’s Clubs, requesting that a King County legislator sponsor the bill. Eventually Washington’s Federation of Women’s Clubs endorsed the eight-hour initiative. The Waitresses’ Union led this coalition, a remarkable alliance of women from every class joining forces to improve their working lives.

Representatives of statewide women’s clubs also joined Lord in advocating that the state Bureau of Labor hire a woman as assistant labor commissioner, who would be familiar with the needs of working women.

More than a militant union advocate, Lord helped waitresses gain respect in the community, and to be seen as a part of it.

--

While identified as a labor organizer, Lord also joined Seattle’s Commercial Club, organized Seattle’s WWI Red Cross headquarters in her office at the Labor Temple, and became an articulate advocate for children’s playgrounds in the city. Lord put a human face on women’s labor issues, and she emerged as a valuable civic activist, equally at ease speaking about issues to the Daughters of the American Revolution or the Seattle City Council.

A tireless advocate for women’s issues of all kind, she was also a figure in the suffrage movement, pushing to give Washington women the right to vote. This was another initiative that bridged the gap between society women’s clubs and the working women’s labor movement.

In 1906, the Washington Equal Suffrage Association held their annual convention at the Labor Temple in Seattle, and Lord was a prominent speaker on the program. When Washington women achieved the vote by statewide referendum in 1910, they exercised their new franchise to elect legislators sympathetic to their issues, including wage and workplace concerns.

Six years later, Lord decided to dive into state politics herself and ran for her district’s Republican nomination for the State Senate. Despite the endorsement of the Central Labor Council, she lost in the primary.

In Olympia, Lord became so identified with the eight-hour day initiative that the legislation, when introduced in 1905, was widely known as the Waitresses’ Bill. One waitress remembered lobbying the legislators, saying “We’d buttonhole those old legislators with their whiskers and long beards, and we’d talk to them until they finally gave in!”

The story widely told of Lord – that she walked from Seattle to Olympia to save her union the cost of carfare – dates from this period. In 1911, the Waitresses’ Bill became law. In 1913, the Washington legislature enacted a $10 per week minimum wage for women, with a few exceptions for agricultural workers. And under Lord’s leadership, the Waitresses’ Union participated in the 1919 General Strike in Seattle – the first in North America – organizing kitchens and “eating halls” throughout the city to feed striking laborers.

Minimum wage, the eight-hour day, and the six-day work week were opposed by a spectrum of Washington manufacturers, who threatened that they would either be driven out of business or forced to hire non-union Japanese labor. Lord rebutted that “if we have to sacrifice the honor of our women for the sake of bringing manufacturers to our state, then we should do without them.”

But Lord was no saint. For example, she fully participated in the anti-Asian racism of her day, shared by labor and management. Seattle’s labor newspaper, the Union Record, referred to a “Mongolian invasion” driving down wages in California, and lectured its readers that “No true unionist will patronize a Chinese laundry” and that good union members would rather “live on two meals a day if getting three necessitates eating in a Japanese restaurant.”

Lord was convinced that competition with Asian men made jobs scarce for white women, and supported exclusionary policies in restaurants. Well into the 1920s, as historian Dana Frank points out, Seattle’s Waitresses Union, under Alice Lord’s leadership, barred Asian-American and African-American waitresses from membership.

--

Lord was not without her critics, though they focused on her gender, not her racial bias. A Seattle editor commented in 1908 that when Alice Lord had the “unblushing, immodest temerity to stand up, the only woman amongst 250 men, and pronounce the benediction (at the Washington State Federation of Labor conference), she has lost all sense of appreciation of modesty and propriety.”

Aside from Lord’s unconventional outspokenness, she didn’t rebut all the era’s gender norms. As late as 1912, the Washington State Federation of Women’s Clubs – Lord’s political allies – pronounced that “home is the natural place for woman and home duties are her natural sphere.”

Lord herself was convinced that housewives were working women in their own right. Consequently, she believed married women belonged at home and should not compete with single women and WWI veterans for scarce jobs. Lord went so far as to assert that married working women were responsible for some of Seattle’s unemployment.

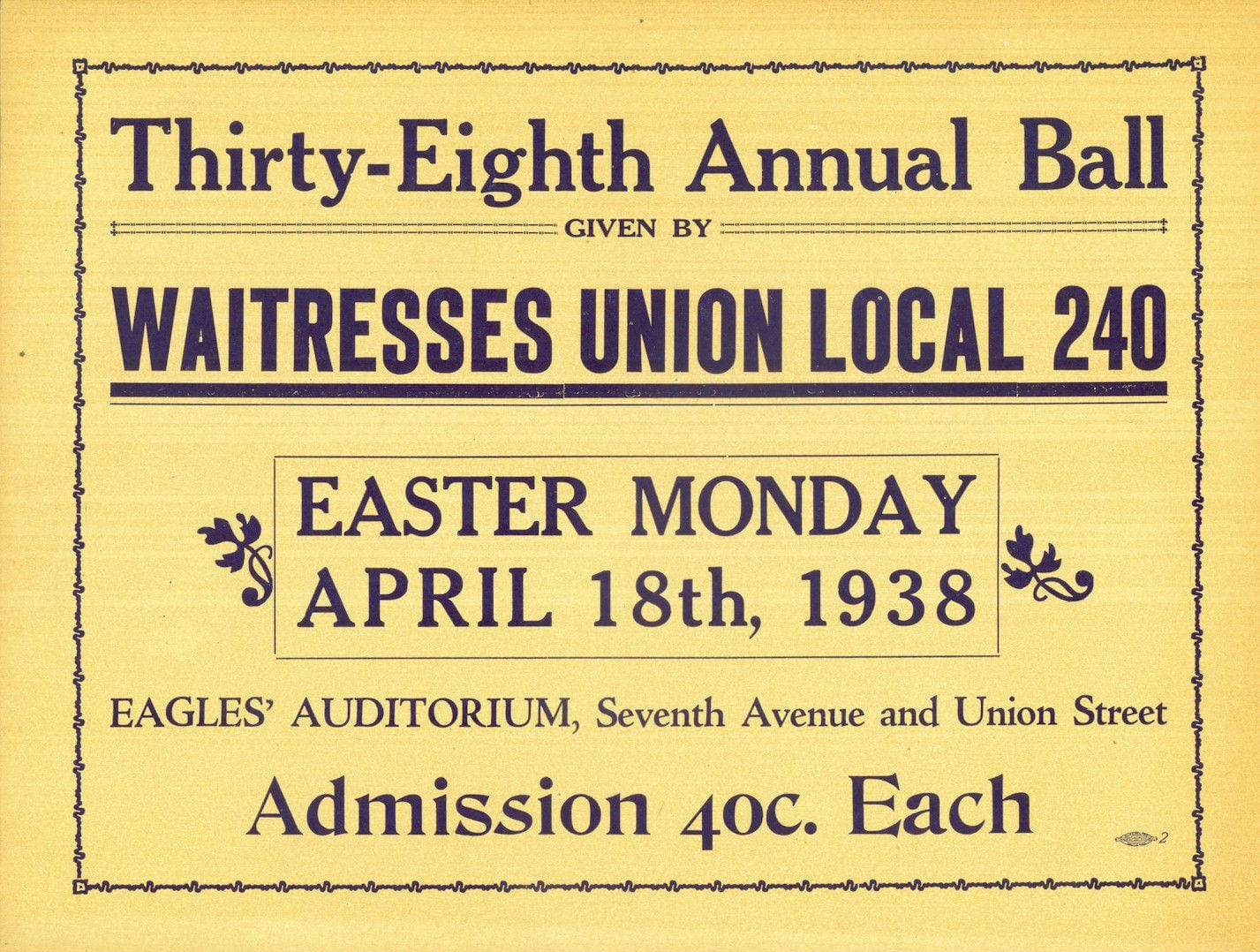

Lord seemed militant and inflexible – even alarming - to her opponents, but her friends and her fellow waitresses saw another side of her. Lord loved card games with her “working girls,” feasts of crab and beer, and singing and dancing. The Waitresses’ Union monthly dances at the Labor Temple were well-known for good food and good music. The Union Record advised its male readers, “Get acquainted with the girl who serves you in the restaurant, and if you’re real good, maybe you’ll receive one of the coveted invitations” to the Waitresses’ dance.”

Asked whether the clouds of cigar smoke at the Labor Council bothered her, Lord laughingly replied that she loved the aroma – but only if it was a union-made cigar.

With other progressive Seattle women, Lord was a founder of the Seattle Industrial Union and Trade School for Girls, where dressmaking, millinery and other industrial trades were taught, to make girls “ready for life.” In cooperation with local church and club women, the Waitresses’ Union purchased a home on Capitol Hill, to serve as a shelter for ill or unemployed waitresses, and it became a haven and social center for luncheons and parties.

And Alice Lord was no prude. She sat for years on Seattle’s film censorship board, and often took the minority position when that august body condemned plays as “unwholesome. One suspects she liked beer too much and social control too little to find Prohibition worthwhile — she recommended to women that they instead devote their energies toward “relieving suffering occasioned by merciless employers,” rather than stopping the sale of alcohol.

Lord would eventually marry Walter Dunn, her second husband, when both were in their 60s — the fate of her previous marriage and longtime single status were generally unremarked upon. That was 1934. Only six years later, Lord passed away.

Members of the Waitresses Union at Lord’s funeral.

--

A decade following her death, a waitress who helped Lord found the waitress’ union remembered “the not-so-good old days,” how “long and hard” Lord worked “in the hardest fight of all” – to get the eight-hour day for women.

“Look what we have gained,” she continued, “the five-day week, premium pay for split shifts, paid vacations, time-and-a-half for holidays, and more wages in one day than we used to make in seven.”

By 1950, Alice Lord’s little union — which began with 65 brave women — was the third largest local of its kind in the United States, with 3400 members.

Lord’s place in Seattle history is both major and largely unrecognized. A central figure in metro Seattle’s high water mark for unionization, she and her “working girls” brought women together in a way not thought possible at the time, and forced society to grant them some of the equal treatment and respect they were due.