People have long been fascinated with the poles, north and south, and the race to reach them. Today, the Arctic ice is melting at an alarming rate, for the first time making navigable Northwest and Northeast Passages a commercial reality. Countries across the globe are jostling to secure and expand their claims to territory, access and resources, while researchers are grappling with what a warmer Arctic and Antarctic mean for the vulnerable world.

In the Antarctic, ice was once regarded merely as a barrier to exploration. But late 20th century research has determined that the continent is vital to global health, not only because massive melting of its ice fields and glaciers could raise sea levels by up to 200 feet, but because the frigid Antarctic regulates much of the planet’s climate, making it habitable for modern civilization. The history of its waters and ice tells us much about what has happened in the past and what could happen in our future.

A pair of recent books put past and present in important context. They feature two explorers who had a profound impact on the settlement of the Pacific Northwest, and who led history-shaping expeditions to the icy kingdoms of the polar regions. The history of their work is newly relevant, as climate change has become a widely recognized existential crisis.

Probing icy depths

Captain Cook Rediscovered: Voyaging to the Icy Latitudes (University of British Columbia Press) by David L. Nicandri attempts to rescue the reputation of the famous British sea captain and explorer, James Cook, whose legacy has been battered by the reevaluation of colonialism and Cook’s impact on Indigenous peoples. Nicandri is the former head of the Washington State Historical Society and author of books on Lewis and Clark.

As the leader of three major global expedition voyages, Cook was one of the first to probe the depths of the icy southern latitudes. He set a record for reaching the southernmost latitude south of the Antarctic Circle in 1774. Cook later came to the Pacific Northwest in search of the fabled Northwest Passage, a supposed open water link through the Northern Hemisphere that connected the Atlantic with the Pacific. In the process, he helped extensively map little-known regions of the perimeter of North America, from the Strait of Juan de Fuca, up the British Columbia coast, following Alaska’s perimeter and the Aleutian Islands all the way to Siberia.

Nicandri makes the case for the importance of Cook’s polar probing as an overlooked aspect of his contested legacy. He argues that historians have adopted what he calls a “palm-tree paradigm,” favoring the stories of Cook’s first contacts in Polynesia and his death in Hawaii over many of his other geographic contributions, particularly in the polar regions. Historians, Nicandri argues, have been seduced by “enchanting island venues.” Cook’s fraught anthropological encounters have trumped arguably more important accomplishments. “That the polar zones are lightly inhabited and infrequently visited should not make them less relevant to the study of Cook," Nicandri writes. "Given the current global climate crisis, the opposite could be true.”

Nicandri concludes that Cook’s skill at reading the terrain from a ship, of scoping the waters for clues and of closely observing the icy barriers helped produce an observational legacy of enormous value. His vision wasn’t perfect — he missed the mouth of Columbia River in his voyage up the West Coast, for example —but Nicandri points out that Cook wasn’t instructed to look for the Northwest Passage that far south anyway. At that point he was mission-focused on the north.

Nicandri sees Cook not simply as an avatar of empire, but as one of the Age of Enlightenment. The world Cook observed and recorded with scientific “fastidiousness” led the way to new geographies and unparalleled global connections.

Mapping Puget Sound

In Land of Wondrous Cold: The Race to Discover Antarctica and Unlock the Secrets of its Ice (Princeton University Press), author Gillen D’Arcy Wood, a professor of environmental humanities at the University of Illinois Urbana-Campaign, looks at explorations that occurred in the first half of the 19th century by the British, French and Americans — after Cook’s southern voyages.

These Victorian era explorers, it's true, may have been looking for new commercial whaling grounds or sources of fur seals. But they were also spurred by reports of imagined islands, phantom coastlines and a desire to draw accurate maps of the region. And they wanted to know: Could the wall of ice be hiding habitable and arable land?

In America at the time, the public was gripped by the popular crackpot “Hollow Earth” theory promulgated by a man named John Cleves Symmes. He traveled the country lecturing on his conviction that the world was a series of concentric spheres, one within the other, housing rich and possibly inhabited lands. Entrances to this wonderland — and the idea, by the way, that inspired Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland — were at the north and south poles. The Earth was like a large bead with an inviting interior. The prospect rallied the American public in favor of finding the truth of Terra Australis Incognita. Thus, a nautical expedition was dispatched, in part to get answers. The voyage was led by a young U.S. Navy lieutenant, Charles Wilkes.

From 1838 to 1842, the Wilkes-led U.S. Exploring Expedition spanned the globe on a scientific mission to seek knowledge and territorial discoveries. In the course of that voyage, Wilkes explored the treacherous Antarctic and is largely credited with discovering enough land — some 1,500 miles of ice-bound coastline — to declare Antarctica a continent, rather than a mere island or remote peninsula.

While Wilkes was sailing the world, the Oregon country opened to the mass migration of American settlers — the first wagon train on the Oregon Trail left in 1836 — to counter British claims in the region. After the Wilkes expedition’s Southern sojourn, his ships sailed here to more thoroughly map Puget Sound and scope out the interior of the Columbia River country in what is now Eastern Washington. A party was also sent by land from the vicinity of present-day Portland to California. All of this was part of solidifying a U.S. presence and to conduct a more detailed survey of region.

America’s ambitions, not unlike Britain’s, were globally expansive. Mapping the planet and studying it served economic interests, colonization and human knowledge. The ships sent abroad were filled with specialists in botany, astronomy, geology and other scientific disciplines. The expensive effort to learn more about the globe and its flora and fauna was an expression of international strength, ambition and naval capabilities. Only large powers could afford to take such risks. Today, nations do the same thing, making technological statements by sending probes to the moon or Mars. So do our planet’s billionaires, like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. The subject of colonization openly rides on the heels of these missions. Are other planets habitable? Who will they belong to? What is the lay of the land? Cook and Wilkes would be familiar with these questions.

A survival story of our own

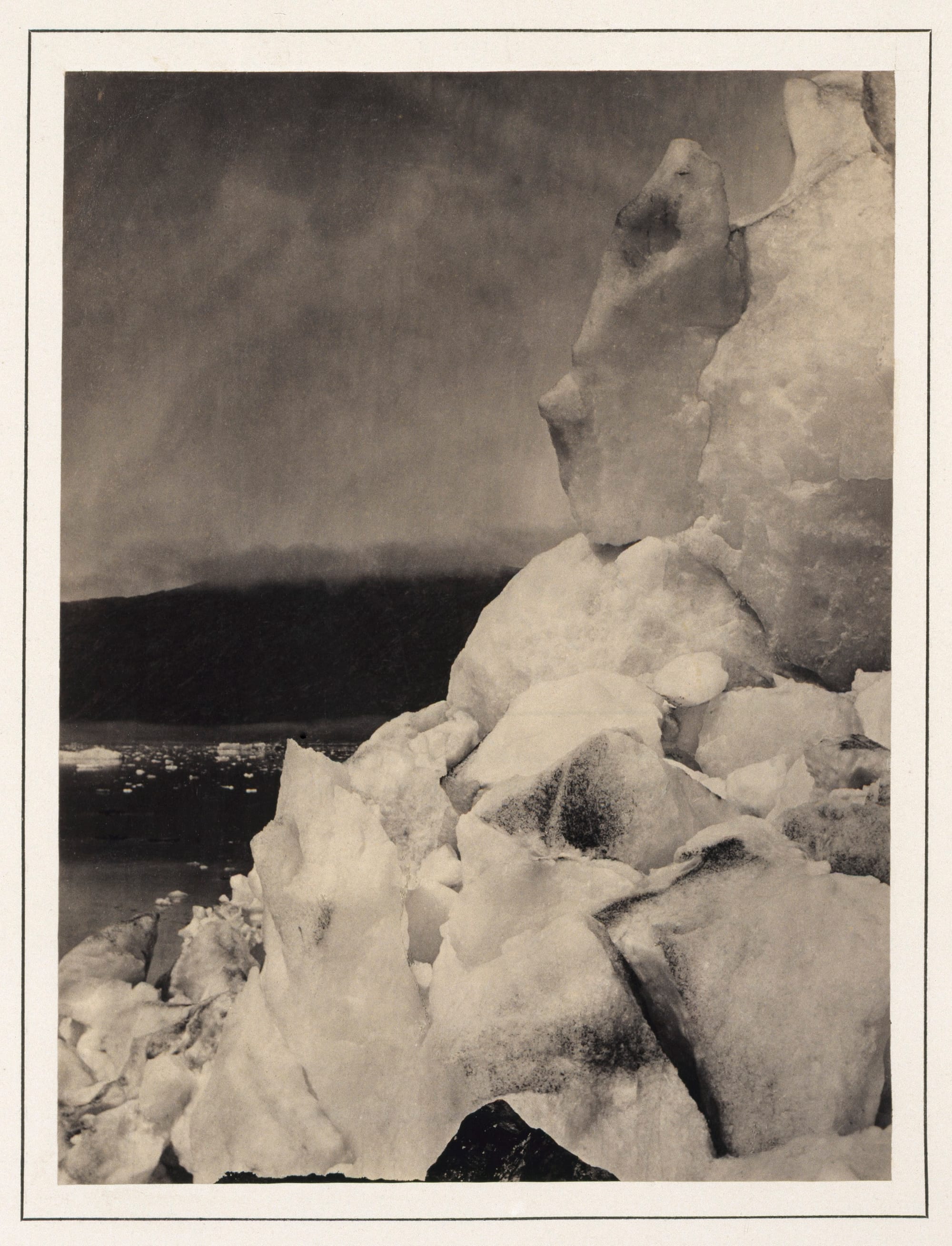

The risks of exploration were great for Cook, Wilkes and others. Wood also recounts the expeditions of British explorer James Ross and the Frenchman, Dumont d’Urville. Crews in wooden sailing ships braved unimaginably massive ice mountains and frigid winds, huge stretches of ocean uncharted, a continent undiscovered. They had relatively few instruments with which to understand what they were looking at: mirages that threw up images of ice sculptures that resembled cliffs or even cities, tricks of light, the aurora australis and frozen seas that defied then-current theories that sea water could not freeze. Was it so strange that open seawater might connect the Atlantic and Pacific at the poles? Or that a hole at the end of the earth might lead to more wonders inside the planet? The otherworldliness of the cold regions invited intense speculation.

We are finally coming to understand the real global importance of the polar regions. Antarctica’s significance did not lie in that it was a continent to settle or a gateway to earth’s interior, but rather in its ability to unlock an understanding of the world. That is why we have spent more than two centuries researching it in cooperation with scientists around the world. Locked beneath the polar ice are the secrets to the mechanisms that help run and regulate the planet, and have done so for millions of years. We didn’t colonize the ends of the world, but realized instead that these remote “wastes” dictate our future survival

Wood offers examples by interspersing in his book 20th century discoveries, such as drilling for core samples in the ice and the seabed to see what Antarctica was like when there was no ice. Or trying to assess the speed and consequences of a warming or cooling climate through the lens of past shifts, including eras when carbon in the atmosphere was at or near today’s high levels. “[T]he business of Antarctic data collection is an empire unto itself, a vast domain,” Wood writes. “Though Victorians retreated in awe from the ice continent, stymied in their efforts to make landing and claim the pole, they are its true founders as an object of knowledge.”

Both books are full of adventure and hardship — stories of people at sea in strange and often harsh conditions. But they also carry lessons about the importance of obtaining knowledge to understand better our blue marble of ice and fire, what makes it tick and how, like adventurers, we are caught up in a survival story ourselves.