The final print editions of Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post published Thursday, marking the end of an era for longtime readers who relied on the papers for news about the city’s Asian American communities.

In December, the papers’ leadership announced plans to sunset the print and online versions of the Seattle Chinese Post, a Chinese-language newspaper that publisher Assunta Ng founded in 1982 with the city’s immigrant population in mind. It was very hard for people who didn’t speak the language or understand the culture, said Ng, who was born in China and raised in Hong Kong.

A year after she started the Post, Ng founded Northwest Asian Weekly, an English-language sister publication. With a younger, more racially diverse readership than the Post, the Weekly will stop printing, but continue publishing online.

These papers, among a handful of Asian American news outlets in Seattle, empowered readers by keeping them looped in on issues in their communities. However, the costs of print, combined with its lack of popularity among younger audiences, played into Ng’s difficult decision to stop publishing the paper editions of the Weekly and the Post.

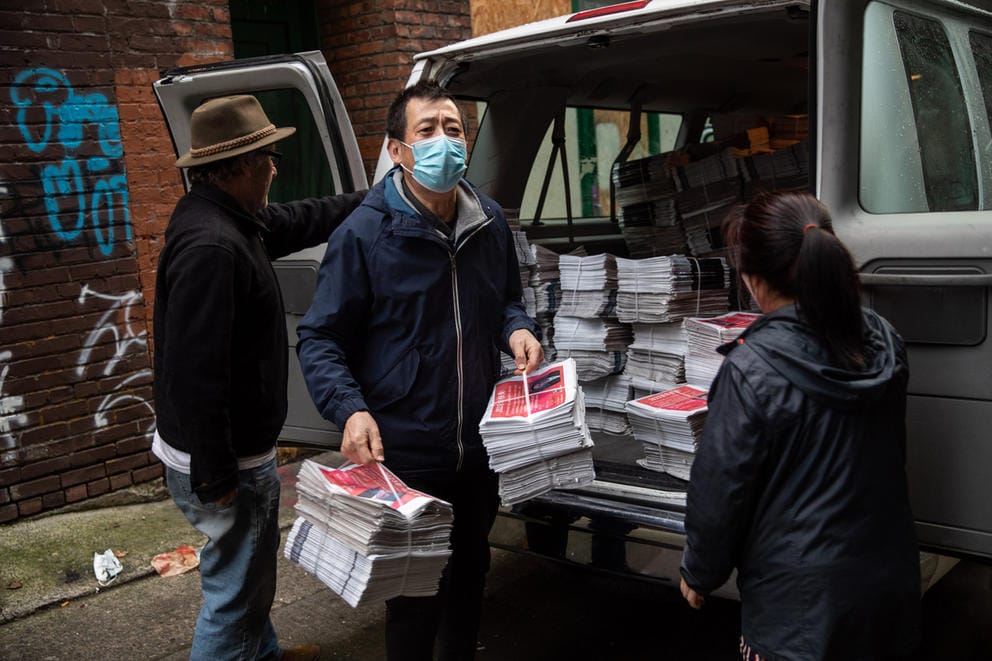

Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post prepare their last print edition. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Some community members knew these changes could be especially hard on older readers. Julie Neilson is an asset manager at the InterIm Community Development Association, a nonprofit based in Chinatown-International District.

“Young folks can get the news from [the] internet, but some senior people who don’t have [an] iPhone, they don’t get the access for local news in Chinese,” read a text message from a community member Neilson consulted. “As I know, most of the Chinese people in the community are limited [in] English and they read the Chinese newspaper like me.”

Seattle Chinese Post workers and Pacific Publishing's driver load in the last print editions of Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post at their offices in Chinatown-International District. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Building trust among Asian American communities

Former Washington governor Gary Locke, the country’s first Chinese American governor, remembered his late mother as an avid Seattle Chinese Post reader. The publication was a source of information for older community members who are homebound or didn’t get out much, he said.

The Post and the Weekly, which share a newsroom in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, galvanized and motivated the city’s Asian American communities, said Locke, who enjoyed picking up physical copies of the Weekly.

“Most of the mainstream publications don’t even cover the Asian American community or minority communities in general,” he said. “That’s why there’s such a need for ethnic community newspapers and publications.”

Ethnic media outlets like the Weekly keep their audiences informed and give readers a voice, Ng said.

Ethnic news outlets inform groups that tend to get minimal media attention and can counter mainstream narratives, according to a 2020 report from the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media.

Fresh from the printers, Ya Tong Hen loads in the last print editions of Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Northwest Asian Weekly covers national and international news highlights, while also keeping audiences engaged in local happenings through its reporting, editorials and community calendar.

Publications like the Seattle Chinese Post also make it more accessible for readers to learn about issues that affect them, Neilson of InterIm said.

“Safety is the number-one concern for people living within the CID,” Neilson said. “Without it being in [their] language, the people who are most impacted by this don’t have access.”

In its 2020 report, the University of North Carolina identified around 950 ethnic news outlets across the United States, about 35 of which were dedicated to Asian American communities. In Seattle, The North American Post, dedicated to the city’s Japanese community, and the International Examiner, a newsroom in the Chinatown-International District established in the 1970s, serve a purpose similar to that of Ng’s newspapers.

“I think there’s a lot more trust within our community to talk to somebody like the Northwest Asian Weekly,” said Jill Wasberg, InterIm fund development and communications director and a former editor-in-chief at the Examiner. “In the International Examiner, where we’ve built these relationships with people in the community, they see the paper, they see the masthead. It’s familiar to them.”

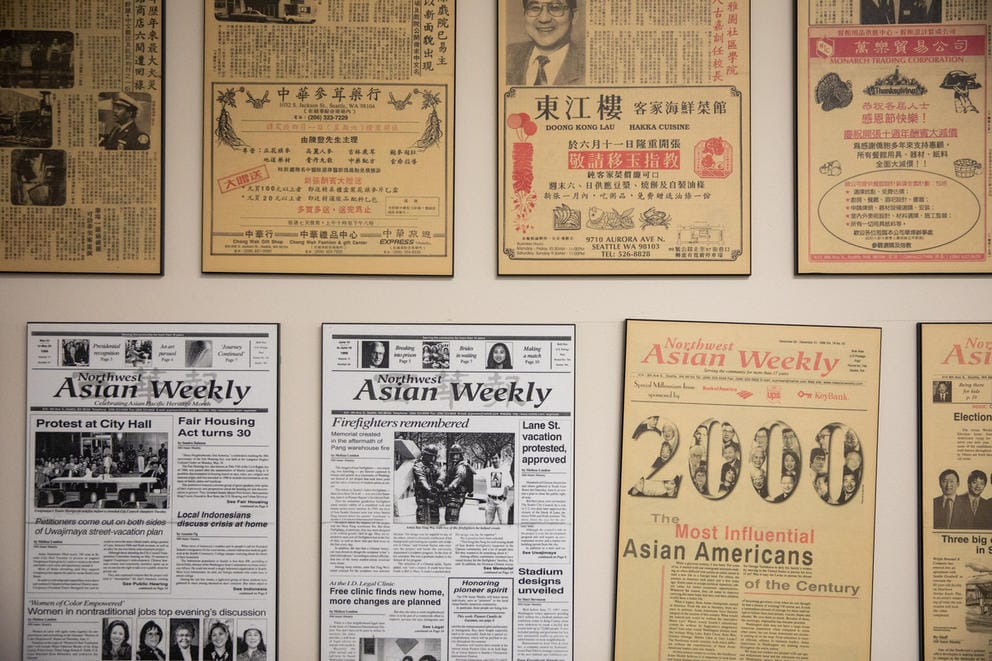

Four decades of print issues of Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post hang on the walls of their offices in Chinatown-International District. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Deciding to move online

Ng recalled one person crying when he learned of the plans to shut down print, a reaction that seems to speak to the general sentiment among readers and community members. Accompanying that disappointment, however, is understanding.

Paper isn’t always easy to operate because it can be expensive, said Tony Au, who has known Ng for decades.

Ng also said print is less popular among younger readers.

More than 80% of people in the 18-to-29 age group prefer to get their news from digital devices, compared to 25% of people ages 65 and up, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey. More than 10% of people in the older age group said they prefer print publications, a larger percentage than in any of the younger groups.

Older readers’ reliance on papers may be more than a simple matter of preference.

“A lot of people still depend on papers … It’s very convenient for the elderly,” Au said, noting older people don’t always have computer access.

The number of people aged 65 and older who have a broadband connection at home has generally trended upward since the early 2000s, according to the Pew Center. As of 2021, 64% of people in this demographic reported having home internet access, less than younger demographics (including 70% of people 18-29, 86% of people 30-49 and 79% of people 50-64).

Dr. Ming Xiao, who has advertised her chiropractic office in the Seattle Chinese Post, regularly read the paper.

“They gave us a great value,” she said, adding she received the paper weekly at her office. “Every week, when I get the Seattle Chinese Post, I’ll read through it quickly and get all the news.”

From left: Nancy Chang, R. Chan, Yuxia Li and Ya Tong Hen prepare the last print edition for Northwest Asian Weekly and the Seattle Chinese Post. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Ng’s legacy, and what’s next

After a successful four-decade run, Ng thinks it’s time to move on.

“I’ve done my part,” she said. “I think it’s time for me and my family to do something else … That will free up my time so I can pursue things that I want to do in the last chapter of my life.”

Besides, it’s not all doom and gloom for Northwest Asian Weekly.

Ng pointed out that news will come out faster now that the publication isn’t bound by a weekly schedule. And people have expressed to her that they are willing to help fundraise to sustain the Weekly.

Community members will have to adjust to the Post’s absence and the Weekly online-only model, but through it all, Ng’s contributions to the community have not gone unrecognized.

“Assunta has been a force of nature and she’s such an incredible community leader,” Locke said. “She’s the heart and soul of both the newspapers … I know that Assunta will continue to be a leader in the community. No one can silence her voice.”