Kate found out she was pregnant in August 2019 — just a few months after her father had passed away unexpectedly.

She and her husband hadn’t been trying to conceive, but once the shock wore off, it was quickly replaced by a bittersweet excitement. She and her husband had planned to have two children, and were excited to give their oldest a younger sibling, but the family recently moved back to Spokane to be closer to her family in the Pacific Northwest, and that joy was mixed with the sadness of letting go of the dream that her children would grow up enjoying nature with their grandfather.

As soon as the couple found out the baby’s sex, they named their son David John. David meant “beloved.” John meant “with God.”

Just after Thanksgiving 2019, her care team at Providence’s Sacred Heart Medical Center informed her that David John had a fatal case of trisomy — each of his genes carried three copies of a chromosome, instead of two. The best-case scenario, they told Kate, was that she would carry her child to full term, and he would live for up to 48 hours sustained only by tubes and ventilators. More likely, though, Kate’s pregnancy would naturally terminate itself at some point.

Nonviable pregnancies are relatively common, and often result in a miscarriage — the natural loss of a fetus before 20 weeks of gestation — or a stillbirth, the same result, but at a later stage of development.

As an older mother, though, and one with a “lazy uterus” (a condition that left her prone to hemorrhaging after giving birth), any pregnancy was an increased risk for Kate, and a nonviable pregnancy was even more so. The best-case scenario — giving birth to a child who survives only by mechanical means, and only long enough for she and her partner to say goodbye — was an emotional weight she wasn’t sure she could bear.

“I don’t want that for my baby,” Kate said. “They couldn’t tell me that that wasn’t going to be painful for him.”

Either of the worst-case scenarios could easily lead to her death. In one, her body would reject the pregnancy but not be able to pass it, leaving her at risk of sepsis. In the other, even if her body was able to pass the fetus, she could die of blood loss. (A risk that was later validated.)

And no matter what, she needed to be in a hospital to ensure any hemorrhaging that happened could be mitigated by professionals. If she miscarried at home on whatever timeline her body chose, she might not be able to get to the hospital fast enough to triage the bleeding. “We both could have died,” she said.

Given those choices, Kate didn’t feel like she had any other option but to terminate her pregnancy in a controlled setting.

Her hope, then, was to get a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure — a surgical abortion — performed at Sacred Heart with her husband in the room and her OBGYN on standby, a procedure the hospital’s policies allow when it’s deemed medically necessary to save the patient’s life.

But because she was pursuing the procedure before her pregnancy had become immediately life-threatening, Sacred Heart’s policies considered it “elective” and therefore wouldn’t allow it. Meanwhile, her husband’s insurance — provided through the Catholic institution he worked for — wouldn’t cover the nearly $8,000 price tag she was quoted for the procedure at MultiCare Deaconess Hospital.

And so, just a few days before Christmas 2019, Kate sat in the Planned Parenthood lobby surrounded by strangers, an IV sticking out of her arm. Her mom and husband had joined her at the clinic, but because of domestic-violence policies in place at Planned Parenthood, that support would have to stay in the waiting room. As soon as her name was called, she knew, she’d have to walk down the long hallway by herself and undergo the D&C surrounded by nurses she’d never met.

“You’re very exposed and vulnerable and you’re thinking, ‘Is this the right decision? Am I doing the right thing?’ over and over,” Kate said. Because of the stress of the ordeal, Kate says she didn’t even think to ask if her mother could stay by her side.

When a nurse told her they were ready for her, all she could think was, “This is the last time I’m going to have my very-much-wanted baby.”

When Kate made it back to the operating room, she finally “lost it,” sobbing to nurses she would never see again. She wanted her husband, wanted her mother, wanted the OBGYN she’d become comfortable with over the past few months.

She wanted to be doing this in the comfort of a familiar environment with familiar people, but here she was, alone.

What happened to Kate — whose full name has been withheld to protect her family’s privacy — is not an isolated incident.

Consolidation and Care

The Seattle Times, using data from the Washington State Department of Health and the Washington State Hospital Association, reported that “48.6% of licensed, acute care hospital beds are religiously affiliated” and deny patients various forms of care through a faith lens — not just abortion, but gender-affirming and end-of-life care as well.

The Keep Our Care Act — a bill currently in front of the state Legislature, sponsored by Sen. Emily Randall (D-Bremerton) and supported by reproductive-rights organizations like Pro-Choice Washington — frames the issue as not exclusive to faith-based hospital systems, saying 50% of hospital beds in the state are “controlled by health care systems that have policies to deny patients reproductive, gender-affirming and end of life care.” (According to Pro-Choice Washington, they rounded up the percentage cited in The Seattle Times.)

In Spokane County, exclusions like this also happen at Deaconess Medical Center in downtown Spokane and at MultiCare Valley Hospital, both owned by MultiCare, a secular, nonprofit health system based in Tacoma. MultiCare doesn’t have a specific policy banning elective abortions, but Deaconess and Valley do.

The Keep Our Care Act doesn’t seek to explicitly require hospitals to provide reproductive, gender-affirming and end-of-life care. The bill’s focus would create a sort of test and process to ensure that as large health systems buy up smaller hospitals, those systems aren’t limiting or discontinuing access to such care at the institutions they acquire.

Keep Our Care would pause health entity consolidations — the term for large corporate hospital systems buying smaller, community-based health care organizations — arguing that such consolidations diminish access to affordable quality care.

If passed, the bill would give the state’s attorney general oversight and enforcement power in cases of consolidation; require a health equity assessment before consolidations can move forward; and strengthen the community input process prior to any potential consolidations.

The process for a bill to become a law is a complex, jargon-filled gauntlet with many places along the way where legislation can be deliberately killed or left to die in committee. In the current legislative session, the Keep Our Care Act is still alive — for now. On Thursday, February 9, it passed the Senate with a vote of 28 to 21, and now moves to the House Civil Rights and Judiciary Committee. The clock is ticking, as the bill has to move through committee by February 21 to stay alive.

Sami Alloy, the interim executive director of Pro-Choice Washington, told RANGE there’s a dire need for the bill to pass now. It was introduced in 2021 but hasn’t yet survived the process to become a law. As legislators and lobbyists have pushed for the past few years to get the Keep Our Care Act on the books and halt health system mergers, more consolidations have happened.

Groups like the Washington State Hospital Association (WSHA) list protecting the ability of hospitals and providers “to continue to merge, affiliate and engage in business transactions” as one of its policy priorities for 2024. They argue that the Keep Our Care Act threatens access to local care and is “a blunt instrument that will stifle the ability of vulnerable hospitals and providers to find partners and keep providing critical services.”

“It seems to us that all parties can agree that we want people to access … high quality and affordable health care services in their communities. As it is currently written, the bill fails to achieve this aim,” said Beth Zborowski, spokesperson for WSHA. “Our concern is that adding several layers of process and cost to an already significant review by the Attorney General puts access to all health care services in some communities at risk.”

Supporters of the Keep Our Care Act think the bill would do the opposite — protecting, not threatening, critical access to care.

“We remain hopeful that our legislative champions will continue taking action to pass this bill because it is a shared priority for Washingtonians,” Alloy said. “But the Washington State Hospital Association is wielding its vast influence and power in the interest of profits over patients. If they continue to stall and delay this bill, patients seeking gender-affirming care, rural patients, low-income patients, will be the first patients hurt by future consolidations.”

Zborowski responded to Alloy’s assertion that failing to pass the bill would harm access to care. “With the current fragility of the health care system in Washington State, clinics and hospitals may not have the resources needed to make it through the process. The alternative to partnership may not be the status quo, but closure.”

“We have tried to work with the sponsor and the bill’s proponents to amend the bill in ways we believe would achieve the oversight the sponsor seeks while adding an expedited emergency review for failing physician practices or hospitals at risk of closure,” Zborowski said. “We’re disappointed that the bill moved out of the Senate in its current form.”

While some smaller hospital systems are struggling, the institutions doing the purchasing are often massive. MultiCare — which became one of two large systems in the Spokane area almost overnight in 2017 after buying the Deaconess and Rockwood systems — had $4.3 billion in revenue in 2022; reported net revenue of around $50 million, the most recent year for which tax documents are available; and describes itself as “the largest community-based, locally governed health system in the state of Washington.” That same year, Providence, Spokane’s other large system, had $6.3 billion in revenue.

Often, though, the issue is that the hospital being purchased is on the verge of insolvency, Zborowski said, citing the example of Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital, which MultiCare purchased in January 2023. “At the time MultiCare came in, the hospital had about 30 days’ cash in reserve and was closing services to stay afloat.”

Yakima Valley Memorial is the only hospital in the area, and MultiCare’s policies for the facility state that “Pregnancy termination may be performed by some Yakima Valley Memorial physicians in very specific circumstances.”

And while the phrase “hospital consolidations” might sound blandly economic, these mergers have real impact for people. Consolidations lead to less competition among systems, resulting in less consumer choice in mid-sized cities like Spokane and the Kitsap Peninsula and even monopolies in less populous areas like Yakima — all of which have been shown to lead to higher prices, higher readmission rates and lower quality of care.

“We can’t undo hospital consolidations once they happen, so every year the Keep Our Care Act doesn’t pass is another year that a community and its patients could be stripped of quality health care options for the sake of corporate control,” Alloy said. “As more and more patients from Idaho and around the nation access care in Washington because of their draconian bans on care in their own states, it’s absolutely vital that we protect care in Spokane and throughout Eastern Washington as a sanctuary for those patients.”

“God bless mergers”

During the final floor discussion before the February 8 Senate vote, a group of mostly Republican lawmakers spoke against the bill, calling it unnecessary and potentially damaging to communities served only by small hospitals that might need bailing out by larger systems.

“This isn’t needed. It’s not needed. If it is, you can do it another way,” said Sen. Shelly Short of the 7th district, which covers much of northeast Washington. “Don’t bludgeon an entire system because of the few that may indeed be impacting access.”

Sen. Keith Wagoner from the 39th district (which covers rural parts of King and Snohomish Counties) said that in 1986 he was melting lead in his basement when it exploded and blinded him. He got care at United General Hospital, a 35-minute drive away. About 20 years later, that hospital almost went under, but was saved by a merger with PeaceHealth.

“These hospitals are important. They’re important to folks like me whose career could have been over,” Wagoner said. “So God bless United General and God bless mergers, because I don’t know if that would be allowed under the policy we’re considering.”

Also speaking against the bill during the debate on February 8, Sen. Mike Padden from Spokane Valley — who has sponsored bills this year to ban gender-affirming care and make performing an abortion a felony — read the First Amendment aloud on the floor, stating that he thought the Keep Our Care Act ignored “freedom of religion.”

“Certainly, these hospitals should be able to continue to honor their mission and provide care and a lot of charity care to folks,” Padden said. “I do not want to see the First Amendment violated by this bill and I’m afraid that the attorney general, whoever she or he may be, [would be] given potentially unconstitutional authority to approve or deny mergers based on violation of the First Amendment.”

In Washington, 41% of hospital beds across the state belong to Catholic health care facilities like Providence, which operates Sacred Heart Medical Center, where Kate had planned to have David John. Many of the major mergers that have drawn attention in the past few years have been Catholic health systems acquiring smaller health systems that are not religiously affiliated.

While Washington is often touted as a sanctuary state for patients from other states to access reproductive, end-of-life and gender-affirming care, that access is often the first thing to go under religious hospital policies, and Washington has one of the country’s highest rates of religiously affiliated hospitals. Four cities and their surrounding communities have access only to a Catholic hospital: Bellingham, Centralia, Walla Walla and Yakima.

Besides Providence and MultiCare, Spokane is also served by CHAS Health, which provides access to low-barrier, nonprofit care, including gender-affirming care, but does not perform “elective” abortions. Tamitha Shockley French, spokesperson for CHAS Health, clarified in an email that because CHAS Health is a federally qualified health center (FQHC), it is “subject to legislative mandates including the prohibition of providing abortions,” under the Hyde Amendment.

Deaconess’ policies also do not allow doctors to perform abortions or prescribe Death With Dignity medications.

Kevin Maloney, MultiCare’s spokesperson for the Inland Northwest and Central Washington regions, didn’t answer RANGE’s direct questions for why at least some MultiCare facilities in Western Washington allow for these procedures but their Spokane County facilities explicitly don’t, but provided the following statement:

“MultiCare providers can offer a range of maternity services and referrals at their discretion but are not required to do so. We encourage patients to have this conversation with their individual provider to develop an individualized health care plan that fits their needs. This is not a new position for MultiCare, but one that we have been committed to for decades as a community-based, secular, not-for-profit health system.”

Kate told RANGE that, though Deaconess’ posted policies don’t allow for “elective” abortions, staff told her they would have been able to help her terminate because it was a “nonviable pregnancy.” She ultimately chose not to get the procedure done at Deaconess because her husband’s insurance would not cover it, and out-of-pocket it would’ve cost her around $8,000 there.

According to Spokane City Council Member Paul Dillon, who previously worked for Planned Parenthood, the Planned Parenthood clinic is the only place in Spokane where someone could get an abortion deemed “elective.”

“Our U.S. healthcare system is set up in a way where abortion providers are very much singled out. There’s the Hyde amendment which bars federal Medicaid funding from going towards abortion providers. There are really burdensome codes and regulations that chip away at access and prevent a lot of providers from having the ability to provide care,” Dillon said. “Planned Parenthood has had to step in despite insurmountable odds to provide safe, accessible abortion care.”

You don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone

Options are also limited for transgender teens seeking gender-affirming care in the region.

Teens who spoke with RANGE, though, described CHAS Health as a bastion of care. Most pediatric providers in Spokane don’t offer gender-affirming care — like prescribing testosterone and medicines colloquially known as “blockers,” which prevent puberty from starting — to individuals under 18. While telehealth has become a more widely available option since the COVID-19 pandemic, many teens want or need care in-person, with someone who can closely monitor their patients.

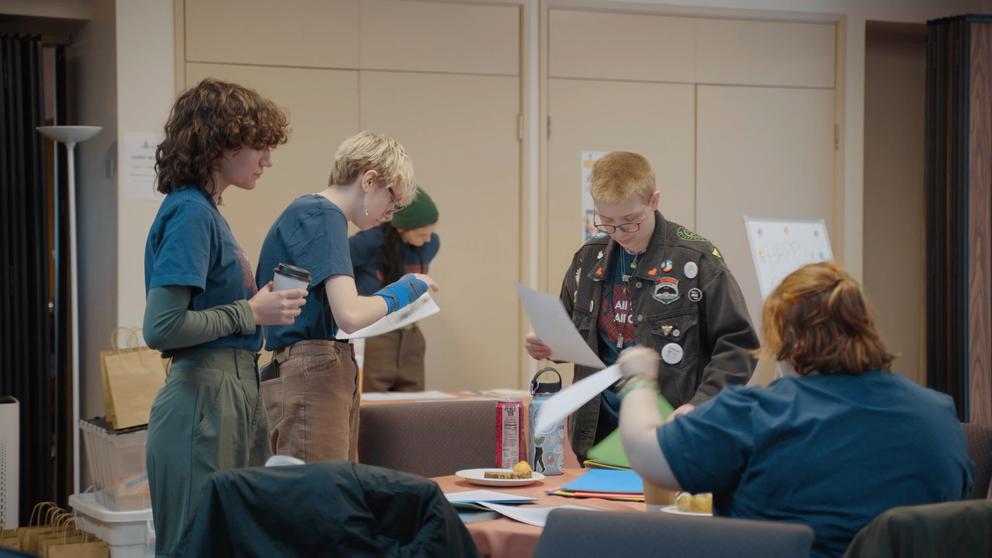

Students from The Community School in Spokane prepare to talk to legislators in Olympia. (Joseph Peterson for RANGE Media)

Albert, a student at the Community School whose full name is being withheld to protect his privacy, is one of those patients. He, and two of his classmates, see the same doctor at a CHAS clinic: Dr. Sasha Carey — one of the only providers in Spokane who offers gender-affirming care to minors.

As part of his transition, Albert takes testosterone. But even though Albert has a supportive family and medical provider, Carey is so booked up it’s difficult to keep Albert’s care plan on track.

“It’s just been difficult to stay on schedule,” he said. “I was supposed to start weekly injections at my six-month mark, and I started them at my nine-month mark because we just couldn’t get an appointment because she’s so busy.”

At one point, Carey went on leave because of a death in her family. Albert had been hoping to get his dose of testosterone upped, but when he called CHAS, he was told the only option was to wait for Carey to return. No one else there could prescribe his medication.

Albert, and his classmates at the Community School, fear that if hospital consolidations continue to happen, their already limited access to care will only decrease.

“My quality of life was significantly worse before I went on testosterone,” Albert said. “It’s lifesaving care that is really important to a lot of people, and if we lost access to that care, that would be detrimental to so many lives. It would be really bad.”

That passion spurred Albert and his classmates to go with Pro-Choice Washington to Olympia to try to persuade legislators to pass the Keep Our Care Act this year. The students met with legislators to share their personal stories and hopes for the bill to pass.

“It matters more than the average person might think it would, because you can think, ‘Oh, hospital consolidations, all these big things are above my pay grade, it’s not my thing to deal with,’ but it really is. Because it affects the entire community,” said Sadge, one of the other teens in Albert’s class.

Sadge’s job on the lobbying trip was to offer a quick, concise explanation of why hospital consolidations mattered — complete with a Pac-Man-like hand gesture to show larger hospitals “gobbling up” smaller ones, creating a monopoly in a region.

“It’s one of those things where you don’t really realize it until you’re in a position where you need access,” Sadge said. “And by then, it’s kind of too late.”

“I’ve always wanted to tell this story”

Kate echoed this perspective: She didn’t realize the restrictive policies of the hospital providing her maternity care would lead her to a Planned Parenthood operating room, saying goodbye to her son alone.

She also sees parallels in her story with another Kate — a woman from Texas recently denied an abortion because politicians didn’t think she qualified for a lifesaving exemption. For the Kate in Spokane, though, it wasn’t elected officials who denied her an abortion — it was a hospital.

She chose to share her story now in the hope that it will push lawmakers to pass the Keep Our Care Act to help protect others from experiencing the suffering she endured.

“Publicly, I still can tear up about it sometimes, if I really think about what it was like,” Kate said. “But I’ve always wanted to tell this story because I know that not everyone feels comfortable when these things happen and it needs to be known about.”

It wasn’t long after that Christmas in 2019 that she and her husband found out she was pregnant for a third time. Kate was still grieving, and her previous experience cast a pall over the early days of that pregnancy.

“I didn’t allow myself to feel good or hope that she was going to be fine until she was way past the 15-week mark,” she said.

It was a nerve-wracking birth: the baby had fluid in her lungs when she was born and, because of her condition, Kate hemorrhaged “a Nalgene’s worth of blood.” At the end of that short, traumatic labor, though, Kate was overjoyed to hold her daughter Ellie, who has grown into a healthy and rambunctious child.

When she thinks about David John, who she still calls her middle child, Kate imagines him in heaven: “I think that our son David is up with my dad, fly fishing and getting all the grandpa time.”

This story was originally published by RANGE Media on Feb. 11. Sign up for RANGE Media’s free newsletter to get news and tools to make the Inland Northwest a better place right in your inbox.