No one mentioned to the keynote speaker, Sen. Joseph McCarthy, that the Washington State Press Club’s Gridiron banquet was a bacchanalia.

McCarthy’s head juddered in an I’m-a-serious-guy beat, his doughface abruptly draining of color. To the late Seattle Post-Intelligencer writer Joe Miller, the face cried out: “Jeer me.”

“Let me tell you,” McCarthy said midspeech. “I didn’t travel 2,300 miles to be a funny man.”

The air was thick with tobacco and pitched liquor, and the hoots of drunken reporters. At one point, someone tossed a chair.

McCarthy’s sole visit to Seattle on Oct. 23, 1952, to campaign for Dwight Eisenhower and the Republican ticket, was punctuated by gaffes and missteps. Along with his ill-fated gridiron speech, which questioned the anti-Communist bona fides of former Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall, McCarthy was sandbagged during his paid appearance on KING 5 television for impugning without evidence two aides of the national columnist Drew Pearson.

After McCarthy’s speech, Washington Lt. Gov. Victor Aloysius Meyers, a former band leader, traipsed across the stage and seized the lectern.

“Let me tell you,” Meyers said, addressing the Wisconsin senator. “I didn’t walk from the bar across the street to be taken seriously.”

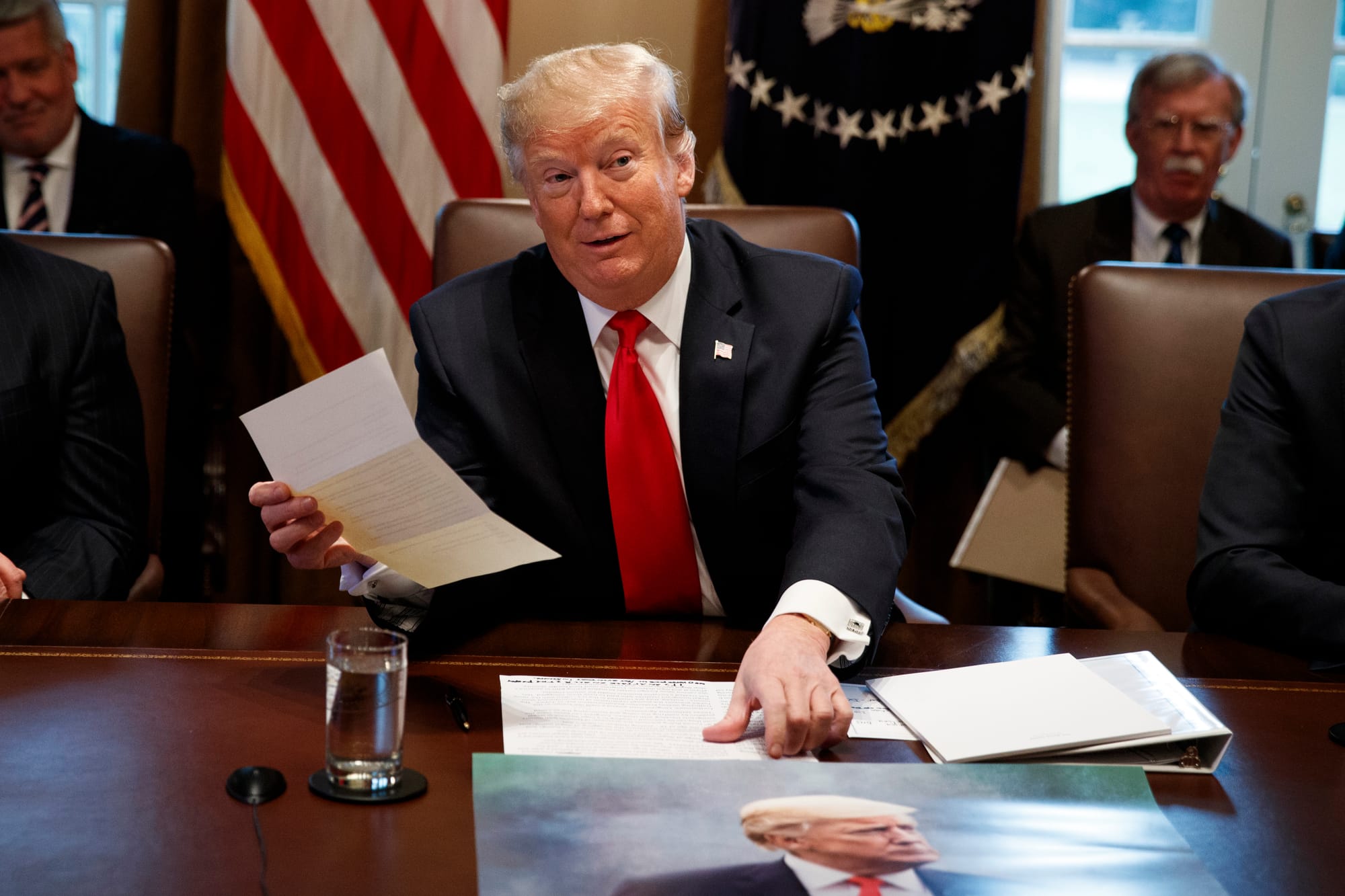

The American Experience’s latest documentary, “McCarthy,” which airs Monday, Jan. 6, on KCTS 9, brings into focus McCarthy’s demagogic legacy, just as it dovetails with President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial in the U.S. Senate. McCarthy-Trump allusions are implicit: In 1952, McCarthy was written off as a paranoid buffoon by the Northwest’s political and media elites, not unlike Trump in 2016.

But McCarthyism, like Trumpism, is a force greater than its namesake. All that’s required is a firebrand to harness extant fear and give it a shove.

By the early 1950, Northwesterners already were smarting from the notorious Albert Canwell Committee hearings. Canwell, a Spokane Republican, served only one term in the Washington state House, from 1946 to 1948, but in that sliver of time he commandeered the chairmanship of the state’s version of the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities to ferret out real and imagined communists at the University of Washington, target labor leader Harry Bridges, and, writes Jim Kershner in HistoryLink, announce that there were “24 identified communists in the Washington state Legislature itself.”

The drama and hokum inspired a play, Mark Jenkins’ All Powers Necessary and Convenient, and ruined lives. (Melvin Rader’s False Witness remains the best primary source).

McCarthyism also had a Northwest signature, a reflection of Washington and Oregon’s gravitational pull of both left- and right-wing forces. Elements of the vociferous anti-communist campaign manifested during the first Red Scare, in response to the radicalism of the Seattle General Strike of 1919, and reared their head in the notorious Goldmark libel case of 1964. State Rep. John Goldmark, a well-regarded Democrat, lost his seat in 1962 after a coordinated smear campaign by the editor of the Tonasket Tribune and members of the archright John Birch Society.

Washington’s first Palmer raid (Alexander Palmer, President Woodrow Wilson’s attorney general, zeroed in on anarchists after a bombing at his home) was launched a few days after the 1919 Centralia Massacre, which pitted American Legionnaires against members of the radical Industrial Workers of the World.

An Associated Press story, which made the front page of the New York Times, noted that 74 IWW members were rounded up in Spokane, along with the editor and a handful of reporters with the Seattle Union Record. As the AP noted, “Governor L.F. Hart of Washington announced he would start a statewide campaign to wipe out the Industrial Workers of the World, Bolsheviki, and other radicals, and called upon all state officials to cooperate in the work with federal and county officials.”

A few McCarthy-era figures still are shorthand in the political vernacular. (Read: You want to be compared to Margaret Chase Smith and her “Declaration of Conscience.” You don’t want to be compared to the vile Roy Cohn).

Cohn manifested a particular kind of evil. He was a toady to his boss and embraced his authority as McCarthy’s chief counsel to smash reputations without cause or documentation. Cohn also is the most tangible link to President Trump, serving as Trump’s mentor and personal attorney. Enraged by the Russia-election investigation, Trump demanded of his aides in 2018, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?” (It’s also the title of a new documentary on Cohn by Matt Tyrnauer.)

While fear of communism was the unifying theme of McCarthyism, Trumpism is more of a mosaic, tethered to a disgust for elites, an anti-immigrant agenda and a push to invigorate a gauzy, golden age of American exceptionalism. Historically, it echoes the populist tone of George Wallace, the xenophobic tenets of Pat Buchanan’s 1992 presidential run, the Gingrich revolution and the Tea Party movement. But it’s less definable ideologically, aligning with an American-style cult of personality, as beliefs whipsaw with Trump’s disparate tweets and remarks.

New York University law professor Norman Dorsen described McCarthyism in Bill Dwyer’s book, The Goldmark Case, as “a particularly irresponsible form of persecution for political beliefs.”

“It also conveys a total lack of due process and fairness whereby unverified allegations, made by rabid and often mercenary ideologues, are used to destroy reputations, careers, and families. Too often these tactics are used against strangers within the gates — recent arrivals to a community who are not of the dominant race, religion, or cultural background,” he said.

Trumpism and McCarthyism share tactical features, consistent with creeping authoritarianism: attacks on the free press and democratic norms, lies and falsehoods amplified by a position of authority and an absence of political courage.

In the Trump era, critics also hanker for a Joseph Welch moment, when the avuncular U.S. army lawyer chided McCarthy, “Have you no sense of decency, sir?”

The Army-McCarthy hearings were the turning point. Disenchantment — a public intolerance of intolerance — sealed McCarthy’s fate and his ultimate censure by the U.S. Senate. But the McCarthy hearings also drew an unprecedented 22 million viewers, in a less fractured media and political environment.

Moments of shame, witnessed by a huge swath of Americans, galvanized the country. Americans today, inured to Trump’s lies, bigotry and attacks, may not feel the same urgency.

Editor’s note: The author’s late father, U.S. Sen. Henry M. Jackson, served as a Democratic member of the Army-McCarthy Committee and was a target of McCarthy’s ’52 Northwest visit. McCarthy was affable in private, the elder Jackson said, but transformed into a paranoid bully in public. Jackson also was repelled by Roy Cohn’s cruelty and delight ripping apart low-level public servants sans evidence.