In the early days of July 1938, a pair of visitors from Germany arrived in Seattle, where they were entertained by local members of the German American community. The two Berliners — Georg Herbert Mehlhorn, a doctor of law in his mid-30s, and his sidekick, Werner Heydenreuter, a tall, blond, 27-year-old athletic trainer — were supposedly on their way to Alaska to hunt after having crisscrossed North America. Starting in New York City in the fall of 1937, they’d logged over 28,000 miles, much of it by car, in a nearly yearlong journey to Cuba, Mexico, Canada, and all across the United States.

During their Seattle visit, locals took them to lunch at Blanc’s, a downtown restaurant favored by the local German business community. They sailed on Lake Washington and visited Mount Rainier. They hobnobbed with prominent Seattle German Americans, talking politics with the likes of Hans Otto Giese, a lawyer and outdoorsman who did work for the German consulate, and Dr. Carl Leede, one of the founders of Swedish Hospital.

Dr. Mehlhorn even gave a brief, if barely willing, interview to an unnamed Seattle Times reporter who visited the pair at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel on Fifth Avenue. The journalist was given a cool reception. “I don’t like reporters,” Mehlhorn said. “They want to know: ‘How about the war situation?’ ‘How about Hitler?’ ‘How does Germany compare to the United States?’ It is annoying to be asked constantly about the ‘war situation.’ We in Germany do not want war.”

The Germans, he averred, are “peace-loving people.” He made no comment about Adolf Hitler. He claimed that Germans know as much about America as does a native of “darkest Africa.”

Mehlhorn might not have liked being questioned, but his real purpose on this epic trip was to get answers. He was not here as a hunter or a tourist. His intended cover was that of a graduate student, but some documents list him as a government official. He was actually a member of the Nazi Schutzstaffel, better known as the SS. His rank at the time of his visit was Standartenführer, the highest field officer rank.

He’d played a large role in expanding the Nazis’ internal takeover of German life. He was one of the founders of the SS’s intelligence service, the feared Sicherheitsdienst (or SD). An early and ardent Nazi, he’d worked for the SD since the early 1930s and rose with the fledgling organization to become administrator of its headquarters in Berlin by the mid-1930s. He mentored Walter Schellenberg, who later ran Germany’s foreign intelligence service. Their boss was the notorious SD leader Reinhard Heydrich, and according to Schellenberg’s memoirs it was Mehlhorn’s administrative skills that “built up for Heydrich the machinery with which he could secretly survey every sphere of German life.” Creating the Nazi police state was just the first phase of his career.

In 1937, Mehlhorn was sent to America by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and architect of the Final Solution, and eventually the most powerful man in Nazi Germany next to Hitler. Mehlhorn’s assignment was to gather intelligence on subjects such as “the Jewish problem in the United States,” “the Negro problem,” the unemployment situation and the state of Bolshevism, the capitalist “desertification” of the soil, and whether ethnic Germans in the U.S. would like to be repatriated to Germany. On entry papers Mehlhorn listed his race as “German” and listed his reason for travel as “pleasure.” It was, however, a work trip.

Mehlhorn’s original reports and correspondence from this mission survived World War II and were recovered by the Soviets. They include a brief summary of his Seattle visit. Copies of these files can be found in the archives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. They run to hundreds of pages and have not been translated from German. Curious to know what he was looking for here and what his impressions were, I asked a local professional translator to translate the section related to Seattle for Crosscut.

Here’s what Mehlhorn said about the people he met in Seattle:

“We established quite good relations with the Germans. In the process, we mainly met only decent people with very clear vision and quite a bit of influence. Of course, as always, the conversations essentially revolved around politics. In line with our previous tactics, we would always just nudge them and then listen carefully to what they said.”

What was Mehlhorn learning? He was taking the temperature of attitudes toward Germany and its treatment of its Jewish population. He reported:

“Now we are in a region where human life is much more pioneering, and therefore the comments are much more open than otherwise in the States. The country is still quite young in its development, and perhaps that is why political involvements are easier to recognize. In any case, communism is strong, and there is an even stronger defense against it here.

“The views of reasonable people here coincide almost completely with what I wrote to you from New York about my view of America’s future. One is almost even more pessimistic. In particular, I’m always reminded of the sentiment against Germany.”

There was strong anti-German sentiment in America during World War I, inflamed by propaganda and anti-immigrant feelings. In some places, speaking German was banned.

“It has been explained to me many times, and without any prodding from me, that the agitation and the actual mood against us are far worse than at the outbreak of the war [WWI]. The Jews and the English are considered responsible. With regard to the former, I am reminded that a possible defense, enabled by the secret anti-Semitism of every American, has been made more and more difficult, especially in recent times, by the fact that even well-meaning Americans no longer believe the assurances about the actual conditions in Germany because individual events in Germany are repeatedly cited as a counter-argument. Especially with the latest Kurfürstendamm history.”

This reference to the Kurfürstendamm appears to refer to Stormtrooper riots along Berlin’s premier shopping avenue in July 1935, which have been described as the most brutal public anti-Jewish attacks since Hitler’s rise to power. The attacks spurred some of the American Jewish community to renew calls for economic boycotts against Germany, and they outraged many outside of Germany, including Americans.

About the Kurfürstendamm incidents, Moshe Gottlieb, in an article entitled “The Berlin Riots of 1935 and Their Repercussions in America” in the American Jewish Historical Quarterly, wrote: “The Berlin Riots mark the turning point in the final annihilation of German Jewry; for these attacks led directly to the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws, the Kristallnacht episodes of 1938, and the ‘final solution’ of the 1940’s.”

According to Mehlhorn’s correspondence, Seattle Germans apparently recommended to him that the Nazis soft-pedal — proceed in a “cool and inconspicuous manner” — when it came to oppressing Germany’s Jews.

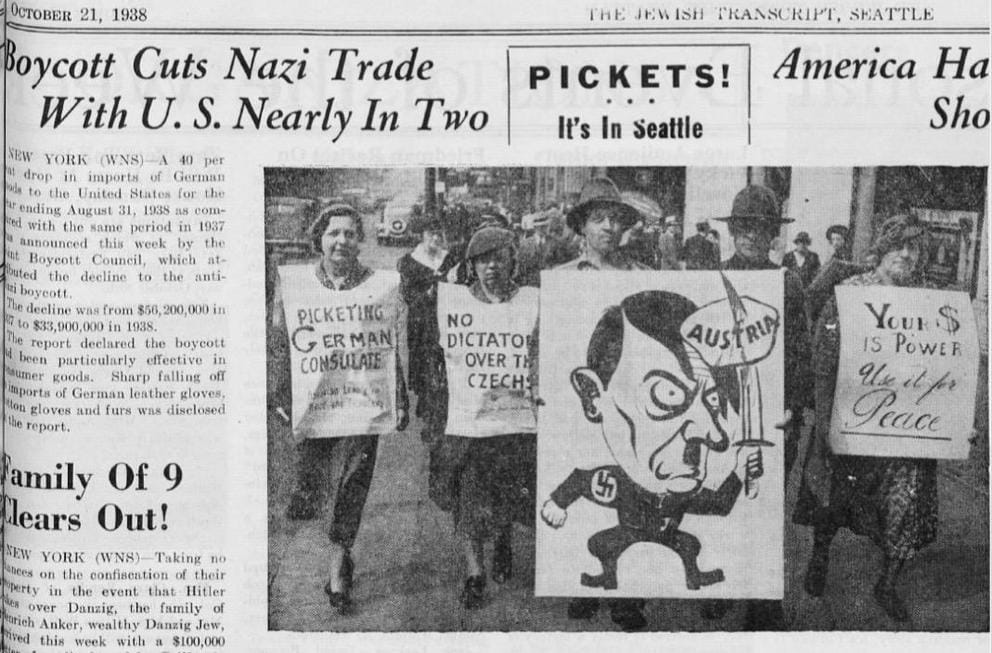

A page from the Jewish Transcript, a Seattle newspaper, dated October 21, 1938, leads with an image of local protesters calling for a boycott on trade with Germany.

“I have, of course, expressed my opinion on this,” he wrote, “and left no doubt that we will by no means be guided in our measures by the blathering of the world. However, it is difficult to fight the argument that we in Germany do have order and that we should be content with the Jewish laws that we ourselves have enacted or else to officially change them.”

Mehlhorn seems to worry that even anti-Semitic Americans were beginning to doubt Nazi intentions. He appears to conclude that this was a public-relations problem perpetrated by Jewish and British propaganda.

Another bit of intelligence, gathered from local German Americans and even some unnamed local “wealthy and influential Chinese” and duly reported to SD colleagues, regarded the timetable for “peace-loving Germany” to prepare for war. Mehlhorn wrote:

“As for the other point regarding the English, the people here are probably right. Those bastards are seriously going to jump down our throats as soon as they get a chance. The general view is that Germany must be ready with its evolution before 1940, and not only in purely military terms, since the decision is expected here for that year.” He was apparently told that the British would move to protect their $2 billion investments in China, which at the time was an ally of Germany. Mehlhorn concluded events were moving quickly and wrote, “We have no time to lose, also not in our internal reorganization of all things!”

Mehlhorn’s takeaway seems to be to make haste for war preparation and speed the reorganization of Nazi Germany. One example of that reorganization was having all police, Gestapo and intelligence services united under SS command.

Mehlhorn’s return to Germany in 1938 plunged him into the thick of German war preparations. He was promoted to the SS rank of Oberführer, roughly equivalent to a senior colonel, and in 1939 was asked to organize the false-flag so-called Gleiwitz incident, in which Hitler faked a Polish attack on a German broadcast station to justify the invasion of Poland. Mehlhorn avoided running the whole operation, believing that his boss Heydrich was planning to eliminate him during the false attack, by claiming he was too ill. He fell out of favor with Heydrich and left the SD.

After leaving the security service, he maintained good relations with Himmler and was appointed to a key administrative post in the occupation of western Poland, which was annexed to Germany and called the Reichsgau Wartheland, or Warthegau. The goal was to Germanize this region through the resettlement of ethnic Germans, in essence to fully absorb western Poland into Germany and replace the majority of Poles with Germans. It was an exercise in ethnic cleansing.

The leader of the effort was the Nazi Arthur Greiser, the Reich Governor of the annexed territory. He appointed Mehlhorn as a deputy in charge of general, domestic and financial matters, and charged him responsible for “all Jewish questions” in the region. Catherine Epstein, history professor and dean at Amherst College, has written that Mehlhorn “exemplified the well-educated, technocratic and fanatically Nazi sort of police official” Himmler liked.

As such, Mehlhorn helped organize the mass murder of Jews, which included the apparatus for rounding up Jews into ghettos. The major one in his administrative area was Lodz, renamed Litzmannstadt by the Germans. The ghetto, second in size to Warsaw’s, became a major source of forced labor, and most of the 200,000 people held there were sent to death camps. Warthegau, Epstein has written, “served as a model for developing the genocide of Jews.”

Early experiments with gas vans — trucks designed to be mobile gas chambers by feeding van fumes into a hermetically sealed compartment — were used in Warthegau in 1941 to kill the disabled, the elderly, women, and children under 14 who were deemed not capable of working. Use of the gas vans broadened to kill Jews, Roma, Sinti, Polish resisters, and some Soviet POWs. A site was created at a vacant estate in Chelmno, where people from surrounding villages and ghettos were transported, stripped, herded into vans, gassed and taken to an area surrounded by forest for secret burial. All of this was done under Mehlhorn’s responsibility for the region’s “Jewish questions.”

While mobile Nazi death squads had been mass-murdering Jews and others in Russia, Ukraine and Poland, Chelmno — called Kulmhof by the Germans — was the first stationary facility to which Jews were transported for the sole purpose of mass killing by gas. The gassing began more than a month before the infamous Wannsee conference where top Nazis planned the implementation of the Holocaust.

The first official extermination occurred on Dec. 8, 1941 — the day after Pearl Harbor. In the first year, according to SS figures, 145,000 died there. Some estimates double that number by 1944. Patrick Montague, in his history of Chelmno, describes it as “a literal death factory” and “the first death camp established by the Third Reich during the Second World War.”

While Mehlhorn was administering genocide, he is known to have one notorious direct connection with Chelmno. Adolf Eichmann was ordered by the head of the Gestapo to visit Chelmno. He watched the extermination process — the screaming of gassed victims in the trucks, the looting and dumping of bodies. He later said “it was the most horrible sight I had seen in all my life.”

Mehlhorn called in forester Heinz May, whose job included the reforestation of the region’s steppe land, and ordered him, under threat of death, to plant trees on the mass graves to further camouflage the operation and mitigate a horrendous stench that threatened the camp’s secrecy. Mehlhorn said if the plantings didn’t work and the graves were discovered, they would insist they were the bodies of dead German nationals. The planting program was unsuccessful, so the dead were disinterred, cremated, and their remains crushed mechanically into dust. This too became part of a template copied at other death camps.

At least one witness reported seeing Mehlhorn at Chelmno in his SS uniform, but others ran the death camp. However, his influence was generally known, if overshadowed by other war criminals. William Shirer, in his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, wrote that Mehlhorn was a “notable instigator of Gestapo terror in Poland.” Units of the SS, Gestapo and police carried out the death policies administered by Mehlhorn. His work was also noted by Hitler: In 1944, Mehlhorn received Germany’s War Merit Cross, a medal created by Hitler himself, which was often awarded to war criminals, including Eichmann, Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller and Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, among others.

The Mehlhorn who visited Seattle in 1938 was a dedicated Nazi, part of a class of SS officers who later felt perfectly comfortable implementing the Final Solution. One wonders if the Seattleites who entertained Mehlhorn in 1938 ever knew of his later role in the Holocaust, or if they ever had second thoughts about the time they spent with him. His real identity wasn’t always a secret, however. Dr. Carl Leede, who took Mehlhorn and Heydenreuter to visit Mount Rainier, revealed in 1943 that he visited Mehlhorn in Berlin at “Gestapo headquarters” in 1939, where they had “a pleasant chat.”

Mehlhorn’s intelligence reports on Seattle shed light on Nazi views of the prevalence of American anti-Semitism and how easy it was to tease out political advice and find quiet support for Germany’s actions against its Jewish population, as well as to spread the idea that Germany’s greater intentions were peaceful.

Mehlhorn survived the war. Contrary to rumor, he was not executed by the Poles, but returned to Germany and resumed legal work. He was reportedly a consultant for Mauser, the arms manufacturer. He died in 1968. A fuller picture of his career and influence is warranted.

Some of the history of pre-WWII Seattle is hidden. Some pro-Hitler local Germans were incarcerated and tried, others changed their views, and after the war, there seemed to be little appetite for an accounting of prewar Nazi advocacy. In recent years, neo-Nazis in the Northwest and the U.S. have become a major topic as the ideologies of the Third Reich are echoed in our country and our region, not only in rural enclaves but pushing their way into our mainstream politics.

The visit of Herbert Mehlhorn, however, was largely forgotten, and his later role in the Holocaust devolved into mentions of a paragraph or two in many books on the Nazi intelligence apparatus and more recent books on Chelmno and its key role as a precursor in what was to come. But the reminders of the ideology he represented are all around us today.

The three-episode U.S. and the Holocaust will premiere on KCTS9 on September 18, followed on the 20th and 21st by episodes 2 and 3. Translations of Mehlhorn’s report by American Translators Association certified German-to-English translator Melody Winkle.