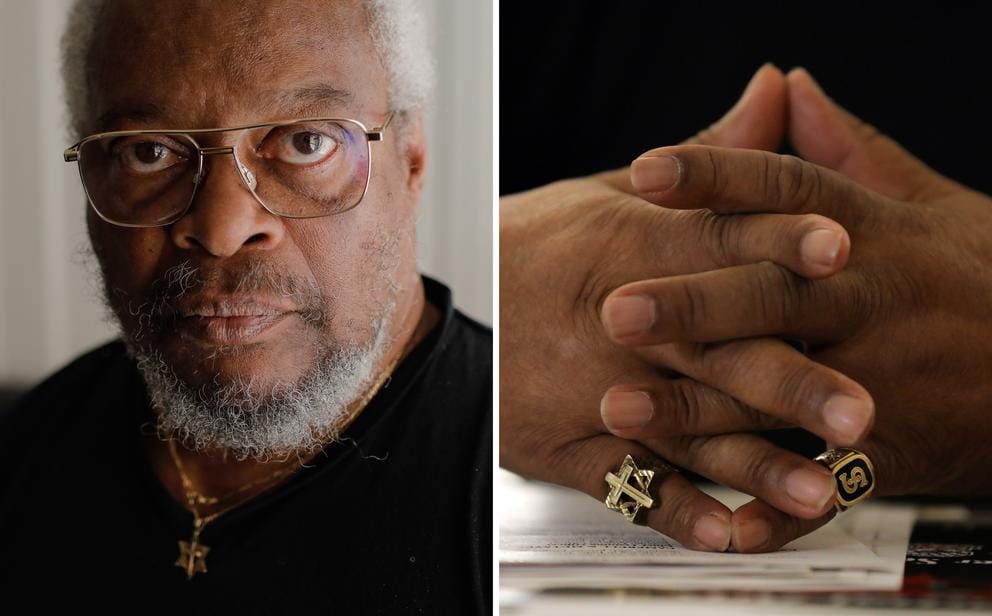

On the wall of Solomon Quick’s apartment hangs a photo of a martial arts class he taught in a basketball gym in Brooklyn. Next to him in the photo stands one of his adult sons, and in front sit several rows of elementary school students.

“I was fast as a cat and hit harder than the parole board,” Quick recalled, sitting at a desk in his small studio apartment in Capitol Hill.

Quick and his wife moved in almost six years ago, keen in retirement to escape the intensity of New York City for the fresh air, green and quiet of Washington. Now 80, Quick still prides himself on his physical training – but a stroke last summer led to him falling behind on rent.

King County Superior Court records show the building’s owner, Biltmore Associates LLC, filed an eviction complaint against the couple on Nov. 7.

Quick is one of a growing number of Washington renters at risk of losing their housing. Eviction filings in Washington more than doubled over the past six months. Monthly filings topped 2,000 in October, a rate that exceeds pre-pandemic levels. The state is on track to eclipse the rate of 2019, when more than 15,000 evictions were filed.

“The magnitude of the increase is unprecedented,” the state’s Office of Civil Legal Aid wrote in a Nov. 13 memo to Superior Court judges.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data["datawrapper-height"]){var e=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var t in a.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;r<e.length;r++)if(e[r].contentWindow===a.source){var i=a.data["datawrapper-height"][t]+"px";e[r].style.height=i}}}))}();

The sharp rise in filings comes after recent years of historic lows, held off by a combination of unprecedented federal aid, temporary moratoriums on evictions and rent hikes, and legislative reforms that fundamentally restructured the legal process landlords must clear to remove a tenant from their home.

Starting in 2020, Congress steered over $45 billion to local governments to help renters who fell behind during the pandemic, but that money ran out in July. Legal aid attorneys, state legislators and tenant advocates cite the gap it left as a major driver of the recent spike in filings. Landlord groups attributed at least some of the increase to repeated filings involving tenants who fell behind multiple times.

This story is a part of Crosscut’s WA Recovery Watch, an investigative project tracking federal dollars in Washington state.

The deluge of filings risks overwhelming the courts. The Office of Civil Legal Aid recently told the Governor’s Office it needs another $3 million over the next biennium to hire 10 more defense attorneys to comply with a 2021 law guaranteeing counsel for all low-income tenants facing eviction – or it may need to pause eviction proceedings to give attorneys a chance to catch up.

While the right to counsel and other tenant protections enacted in recent years have resulted in fewer rulings against tenants in courts, attorneys are now stretched thin juggling higher caseloads. And even if a tenant is able to avoid judgment against them, the eviction process can still derail tenants’ lives.

“We are struggling to fill the gaps right now,” said Philippe Knab, eviction defense program manager for the Office of Civil Legal Aid.

The Biltmore Building on Capitol Hill, where Solomon and Miriam Quick have lived for six years. (Genna Martin/Crosscut)

Pandemic rental aid ends

Eviction filings took a nosedive in 2020 thanks to state and federal moratoriums that restricted evictions under many – though not all – circumstances. They crept back up in 2022 but remained low relative to historic levels, a trend that continued through the first half of 2023.

Multiple factors could be driving the sharp rise in filings this year. Tenant advocates and some Democratic state lawmakers point to double-digit-percentage rent hikes that returned in late 2021 after pandemic-era restrictions expired. They accuse large corporate landlords and property management companies of gouging renters, and propose legally capping rent hikes as California and Oregon do.

Nearly all observers pointed to the end of federal rental assistance this summer as a key factor. That money dried up just as the state ended a pilot mediation program that had required landlords to notify a local dispute resolution center before filing for eviction.

Landlords who previously may have delayed filing while a tenant applied for help through a local nonprofit now have little incentive to wait, said Edmund Witter, senior managing attorney at King County Bar Association's Housing Justice Project.

“They know there’s nothing else out there for them,” Witter said.

More than $1.7 billion in federal pandemic aid flowed to Washington landlords through local governments – clearing debt ledgers for tenants who owed sometimes more than a year’s worth of back rent. That money stopped evictions that had already been filed and kept other cases out of court. But administrative challenges sometimes limited the impact of those programs, with some applicants reporting long wait lists and poor communication. Thurston County suspended its program for months after a dispute with its contractor over audit findings. And millions were lost to federal reshuffling after Spokane and Yakima counties failed to meet spending deadlines.

While the giant pot of federal aid temporarily held off evictions, it masked a deeper dysfunction in the rental market that is now reemerging, a rare point on which landlord and tenant groups agree.

Both sides said it’s possible that the current numbers represent a momentary blip and filings will level off next year. The end of the mediation program could have spurred a short-term bump, and local laws such as Seattle’s limits on winter and school-year evictions may influence when landlords file. But those local and temporary factors seem unlikely to fully account for the consistent upward trend statewide over the past few months.

Others worry that rising numbers signal a wave of housing insecurity to come as the system returns to a pre-pandemic normal, when an average of close to 20,000 evictions were filed each year.

Attorneys at the Office of Civil Legal Aid stress that while the numbers of tenants entering the legal system are concerning, case outcomes for those tenants have dramatically improved in the two years since Washington became the first state to guarantee legal representation for low-income tenants. According to a recent report to the legislature analyzing some 8,000 cases in which court-appointed lawyers defended tenants, judges ultimately issued eviction orders against just 15%. And more than 40% of cases were either dismissed or ended in a negotiated agreement for the client to stay in their unit.

While the office does not have good data from before the 2021 law to compare case outcomes, Knab said he has noticed a paradigm shift in court.

“I heard a judge once say that, ‘We’re not going to hand out writs like candy anymore,’” Knab said, referring to a writ of restitution, the legal term for a ruling ordering a tenant out of a property. “It is sometimes hard to articulate how a lot of these proceedings, and I don’t mean any disrespect to the court, but really were kind of kangaroo proceedings. These weren’t being taken very seriously until there were changes made.”

Family photos hang on the wall of the Quicks’ home on Capitol Hill. (Genna Martin/Crosscut)

A search for solutions

More eviction filings after a historic drop in rent assistance should perhaps not be all that surprising, said Ted Kelleher, housing assistance program manager for the state Department of Commerce. State lawmakers created an ongoing rent-assistance program in 2021 that is expected to distribute about $30 million per year, but that amount pales in comparison to the more than $1.7 billion of federal pandemic aid that went into rent assistance.

“The COVID funding brought us closer to what rent assistance and other assistance looks like being fully funded, and then that ended,” Kelleher said. “Those [current] investments … aren’t at a scale that is going to meaningfully change the trajectory of overall evictions.”

Funding for that new state program could also be jeopardized as its revenue source (document-recording fees on real estate transactions) has recently flagged amid a cooling market.

One obvious answer would be more rental assistance. But tenant advocates say that won’t fix the underlying problem: Rents keep going up.

“Rental assistance alone will never, ever be the answer,” said Michele Thomas, director of policy and advocacy at the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance. Thomas cited a recent survey of roughly 500 Thurston County residents who received rent assistance during the pandemic – half reported they’d already fallen behind on rent again, and three-quarters said they were spending all or nearly all their income on rent and utilities.

“In what world can the [state] legislature afford to keep up with landlords’ rent increases?”, Thomas said. “It’s just this terrible cycle where [renters] are pushed back into the same situation.”

Find tools and resources in Crosscut’s Follow the Funds guide to track down federal recovery spending in your community.

Landlord advocacy groups have vocally opposed past efforts to regulate rents, and spent heavily against a recent renter-protection ballot initiative in Tacoma. They have instead called for officials to increase subsidies to help people who can’t afford rent.

Sean Flynn, executive director of the Rental Housing Association of Washington, which represents property owners across the state, said he believed the eviction filing numbers were inflated by what he called “churn” – the same tenants cycling through the courts multiple times after having a previous case dismissed thanks to rent assistance or other legal interventions.

He said King County courts are now taking significantly longer to process cases once they’re filed, a problem he says has gotten worse in recent years thanks to tenant protections like the right to counsel.

“The 634 in King County in October, I’m sure there’s some frequent flyers in there from June and May,” Flynn said. “We’re feeding people into the system and nothing is coming out the other end.”

Democratic state lawmakers in the House and Senate say they plan to pursue legislation to limit rent increases this session. Previous efforts have failed to move forward in Washington over the past few legislative sessions, even as California and Oregon have tightened limits on rent hikes. Washington state law preempts local governments from regulating rents.

“[Rent stabilization] will be a top priority if not the top priority” this session, said Rep. Strom Peterson, D-Edmonds, who chairs the House Housing Committee. He acknowledged previous bills have stalled in recent years amid Democratic majorities, including in the committee he chairs. But he said the rise in eviction filings, coupled with constituents reporting rent hikes of as much as 50%, convinced him that now was the time for statewide policy action.

“I think we as a legislature have become better educated to what’s really happening with hardworking families and their struggle to stay housed,” Peterson said, noting the electoral success of local tenant protection measures in Tacoma and Bellingham earlier this month.

Sen. Patty Kuderer, D-Bellevue, who chairs the Senate Housing Committee, said she supports capping rent increases but prefers an incentive approach rather than a mandate. Kuderer said she plans to introduce a bill that would extend business and occupancy taxes to include rental income. The bill would allow landlords to avoid the tax if they voluntarily agree to cap rent increases.

Solomon Quick said he found a nonprofit that has offered to cover his owed rent plus three months of advance rent, but building management is asking him to pay an additional $2,377 for their legal fees. (Genna Martin/Crosscut)

Renters on the edge

State officials expect limited ongoing rent-assistance funds available will be triaged to renters like Quick, who are already in eviction proceedings.

Quick found a nonprofit willing to cover the $6,100 he owes and pay three more months in advance. But the building’s property management company, which did not respond to an email from Crosscut, told Quick he needed to pay an additional $2,377 to cover legal expenses before they could commit to accepting the money, according to text messages shared with Crosscut.

Quick had hoped to move into a less-expensive senior living community next February when his lease ends, but he said the retirement community told him they couldn’t accept him because he owed money to his current landlord. He is working with Witter of the Housing Justice Project to convince the property management company to accept payment from the nonprofit. If they don’t, that could bolster an argument for a judge to dismiss the case. His next scheduled hearing is not until April.

Quick remains optimistic despite the uncertainty, he said, comforted by his faith that a higher power will see to it that things work out. But the eviction process can often be destabilizing for tenants, even when financial resources and free legal help are available. And even if the case is dismissed or the judge rules in favor of the tenant, that legal record can follow them, making it more difficult to secure housing in the future. So each filing has repercussions.

“For us to have this conversation, there’s something wrong with that,” Quick told Crosscut. “I shouldn’t have to be going through this, that’s the bottom line.”

Clarification: This article has been updated to reflect that state law preempts local governments in Washington from regulating rents, not the state constitution.

A hallway inside the Biltmore Building. (Genna Martin/Crosscut)