When Maddesyn George of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation stood in court to be sentenced last month, her attorney hoped for two things, but the most important was this: for his client to be heard and believed.

“The judge expressed understanding for the plight of Indigenous women,” said Steve Graham, George’s attorney. “We finally felt heard and listened to and understood.”

U.S. District Judge Rosanna Malouf Peterson also gave George a sentence far below the prosecution's recommendations. In her ruling, she acknowledged the uneven prosecution of the drug charges, cited the Savanna's Act and the Not Invisible Act that address the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and was critical of the prosecution’s handling of George’s case.

Graham believes that this wouldn’t have been possible without the help he received before and during the trial from supporters and advocates, particularly people working for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Washington.

“If it weren't for all the supporters and resources that they brought to the defense, Maddesyn would no doubt be serving a standard range sentence,” he said.

Early on, Graham, who is not a tribal member, reached out to Earth-Feather Sovereign, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colvile Reservations and founder of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Washington, for guidance in educating and directing him to resources and experts on issues specific to Indigenous women.

Yvonne Swan, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, speaks at a rally outside the Tom Foley Courthouse in support of Maddesyn George, Oct. 8, 2021. (Courtesy of the Free Maddesyn Coalition)

Moved to become involved

George’s case reminded Sovereign of a case involving another enrolled citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Yvonne Wanrow (now Swan) was sentenced in August 1973 of second-degree felony murder and first-degree assault for shooting an intoxicated known child molester who broke into her friend’s home and was approaching her 8-year-old son after repeatedly being told to “get out.”

“I, too, was threatened with decades in prison for fighting back against a white rapist,” Swan said in a statement to Judge Peterson. “If she and I were affluent white women, and our rapists were Native men, would the police and prosecutors have treated us so badly?”

Sovereign was moved to become involved and reached out to George’s mother, Jody George. Together, Sovereign and George’s mother gathered support from advocates, organizers, and scholars who work on issues of colonial, sexual and domestic violence; policing and incarceration; and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples. Out of this support, the Free Maddesyn Coalition was established.

Swan’s case reached the Washington Court of Appeals, where the justices had to decide whether Wanrow had received a fair trial after the judge restricted her ability to make a self-defense claim, similar to the debate in George’s case.

Swan’s case “became a powerful means of putting feminist theory into action to fight gender bias in the criminal justice system, and marked the beginning of what came to be called ‘women’s self-defense work,’ ” wrote New York University law professor Elizabeth M. Schneider in her book Battered Women and Feminist Lawmaking.

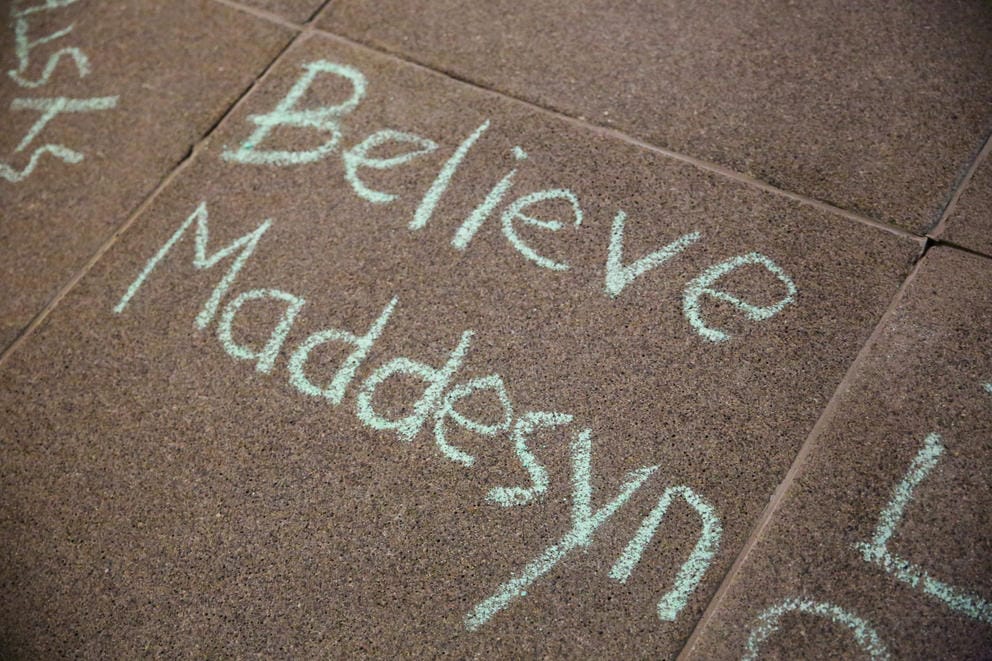

“Believe Maddesyn” is written in chalk on the sidewalk outside the Tom Foley Courthouse in support of Maddesyn George, Oct. 8, 2021. (Courtesy of the Free Maddesyn Coalition)

The bigger picture

According to a report from the National Institute of Justice, more than four out of five American Indian and Alaskan Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime, and more than one in three will be raped in their lifetime. Washington state has the second highest number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, according to a survey by the Urban Indian Health Institute. Data from the Sovereign Bodies Institute showed that Okanogan County, the county George lives in, has had the fourth highest per capita rate of incidents of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the state since 2010.

Last month, George was sentenced to 6½ years in federal prison for voluntary manslaughter and possession of methamphetamine with intent to distribute.

Her mother recalls the day that led to George’s imprisonment.

“She called me when she shot him … right after it happened” she said.

“She said, ‘Mom, I think I’m going to jail.’

" ‘Mom, he was going to kill me. He was coming through that window. All I could think of was Shynne. I can't leave her alone. She needs me. I shot him because he was trying to get me, he was gonna kill me mom.’ ”

When George was arrested, she told the Colville Tribal Police and Okanogan County Sheriff’s deputies that Kristopher Graber, a white man, had raped her the day before. The police recording of George’s account says that when she attempted to fight back, Graber pulled out a gun, left it in plain sight and raped her with a vibrator for 45 minutes. She was able to persuade him to stop by saying she was hungry and waited for him to fall asleep before escaping with the gun he assaulted her with, more than $5,000 of his money and 48 grams of his methamphetamine.

The next day, Graber looked for George on the Colville reservation with a shotgun in hand, pounding on doors until someone told him where she was. When Graber found her, she was sitting in the passenger side of a car, alone. According to the account in court documents, a witness, Martin Stanley, said Graber reached in and hit George, and then she shot him. Stanley told police that George was in danger. “It don't bother him to beat the living shit out of a woman. He's known for that,” he said.

Missing and murdered

Sovereign sees the violence that George experienced and the outcome as an extension of the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

“It doesn't just include when someone's reported missing or found murdered” Sovereign said. “It includes domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking. It includes sex trafficking. All these things that possibly lead to someone making a report that their daughter's missing.”

Because the shooting was on the Colville reservation, U.S. law required George’s case to be moved to federal court, instead of keeping it under Colville tribal jurisdiction. The Major Crimes Act removes murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny from the crimes that tribes can adjudicate in their own communities. According to a National Institute of Justice survey, 97% of crimes committed against Native victims are committed by non-Natives.

The Major Crimes Act is one of many that interfere with the tribal justice system’s ability to protect its communities by prohibiting tribal courts from trying non-Native suspects and limiting the sentencing penalty that tribal courts can impose, according to a statement from Dian Million (Tanana Athabascan), professor of American Indian studies at the University of Washington.

“We find that very few cases of rape or sexual assault are paid attention to, are prosecuted, are given the resources that they need to make our women safe on our own land,” said Abigail Echo-Hawk (Pawnee), the executive vice president of the Seattle Indian Health Board and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute. She led the institute’s “Our Bodies, Our Stories” series of reports that exposed the scope of violence against Native women across the nation.

U.S. Attorney for Eastern Washington Vannesa Waldref and two other attorneys in her Spokane office denied that race factored into George’s case, denied her self-defense claim and argued that George was lying about being raped. The U.S. Attorney's Office declined to comment to Crosscut for this story.

Maddesyn George. (Courtesy of the Free Maddesyn Coalition)

Devaluing Native women’s bodies

Echo-Hawk sees the prosecution’s actions as representative of how the federal government devalues Native women's bodies. She says that devaluation has led to Indigenous women suffering the highest rates of physical and sexual violence per capita in this nation.

“Penetration is rape,” Echo-Hawk said. “Our bodies matter. Rape survivors like myself, we see it, we feel it, and goddamnit we're gonna fight it.”

The prosecution also pointed to some of Graber’s past romantic partners who wrote letters claiming he never was sexually inappropriate with them in any way. “They could not imagine him being sexually inappropriate — let alone raping — anyone,” as evidence that he couldn’t have raped George, the prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memo.

At the sentencing hearing, the judge criticized the prosecution for not mentioning Graber’s ex-wife’s lifetime restraining order, which details her accounts of his strangling her and threatening to cut off her body parts and mutilating her. “He said if he couldn't have me he was going to make sure no one else would want me,” the police report attached to the restraining order said. Among the many accounts of abuse by Graber’s ex-wife was mention of his getting aroused by beating and strangling her.

In a letter to Peterson, the Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs, one of the oldest sexual assault coalitions in the nation and a leader in the anti-sexual violence movement since 1979, addressed the prosecution’s “miscomprehension and disregard for some of the most basic and well-researched dynamics of sexual and interpersonal violence and survival.”.

The organization also pointed out that 63% of rapes are never reported, and experience with racism and police violence make people of color even less likely to report.

According to court documents, George previously experienced police sexual misconduct and harrassment so unsettling that she moved to another town for a while.

Court documents show Okanogan County Sheriff’s Detective Isaiah Holloway coercively obtained George’s phone number and would ask her to come to hotels with him and drink, saying, “If you help me out, I’ll help you out,” according to George’s statement in September. Holloway had nothing to do with investigating the shooting of Graber, but he would have likely been the officer to respond if George had reported the rape because of how few officers work in rural Okanogan County.

Sexual assault experts call for a forensic exam by a trained sexual assault nurse examiner within 72 to 96 hours of the alleged assault to obtain physical evidence. But after hearing George’s account of the rape, and shooting, police sent George straight to Colville Tribal Jail.

Mistrust in the system

Echo-Hawk calls the whole trial and the investigation leading up to it a complete travesty.

“Instead of making sure that there is safety on our lands for our people, for our women, the Department of Justice did the exact opposite, and produced further mistrust in the supposed justice system,” she said.

The Colville Tribal Police has not returned phone and email requests for comment.

For Indigenous supporters of George, in addition to considering her one of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, the separation from her child is a visceral reminder of America’s history of separating Indigenous children from their families.

“We now have a mother who is missing from her family, from her culture, from her community, from her loved ones, from her land, because of this travesty of justice,” Echo-Hawk said. “They have taken this mother from her child, continuing a cycle of colonial violence against Indigenous people.”

George’s mother is raising George's daughter, Shynne, until her release. “I think right now Shynne is what gets me up every day,” said Jody George, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. The chatters and giggles of her granddaughter could be heard in the background, trying to get her grandma’s attention. “She's been there every morning for me, making sure I get up and keeps a smile on my face.”

“Instead of making sure that there is safety on our lands for our people, for our women, the Department of Justice did the exact opposite, and produced further mistrust in the supposed justice system,” Echo-Hawk says.

Jody George she would continue to advocate not just for her daughter, but for all Native people who are incarcerated and treated unfairly in the courts or in jail. “I’m gonna do this for Maddesyn,” she said.

Throughout the trial process, the coalition members became close. George was able to lean on them when things were hard and she needed someone to talk to. Judy George calls them her tribe.

“What we're seeing now is the love of Indigenous communities and women's advocates and other groups coming to wrap their arms around these families,” Echo-Hawk said. “Despite all of this violence, not only have we survived, but we are thriving and we will continue to do so. It's in our thriving that this fight for justice will never end. We will ensure that our women are safe. Five hundred years ago we were the safest people on this land, and we will be that again.”

Corrections: An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of George's daughter and misidentified the jail George was taken to. The story has been corrected.