The founding of Seattle’s first town in what is now Pioneer Square mirrored that of the rest of the country when violent settler colonialism forced Seattle’s first people off their ancestral lands. After a law was passed that made it illegal for any person from the Duwamish Nation to be within city limits after dark, Pioneer Square settlers burned the nation’s traditional cedar canoes, longhouses and potlatch houses, along with all the possessions that remained in their homes.

More than 100 years later, in the heart of Pioneer Square, Chief Seattle Club has opened 80 new affordable housing units in a building they are calling ?ál?al, the Lushootseed word for “home” (roughly pronounced “allall”).

?ál?al is suffused with Indigenous art, culture and culturally sensitive services. Even the building’s construction began with Native tradition.

Before construction started, traditional herbal medicine was put down in the four corners of the ground, and elder Glen Pinkham, Yakama Nation, blessed the ground that ?ál?al would soon be built on. Once ?ál?al was finished, Pinkham followed up with a Yakama cleansing ceremony. Starting from the rooftop, Pinkham went room by room and shared prayers of healing for the future residents. The seven medicines that were put into the ground are now the names of each floor: sage, sweetgrass, cedar, nettle, salmonberry, bear root and yarrow.

At the end of the hallways on each floor there is also a small gathering area with a couch, more art and a large window.

“Those little rooms are very ceremonial,” Chief Seattle Club Executive Director Derrick Belgarde (Siletz/Chippewa-Cree) said. Communal gathering spaces are all seen as ceremonial opportunities for healing, including the residential community room on the third floor. This is a typical amenity space in apartment buildings for birthday parties and other gatherings.

“A birthday party is just as much a part of the healing as the planned-out ceremonies with all the medicines because if you've been on the street for 15 years, your birthday parties have been a lot about self-medicating to get through the fact that the sun's gone around again, and you're still on the street,” said James Lovell (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), Chief Seattle Club development director.

A Chief Seattle Club program manager will also use the residential community room to run programs for everything from moccasin- and ribbon skirt-making to drum and talking circles and support groups.

A depiction of a matriarch in the brickwork, designed by Jones & Jones Architects, outside the newly opened ʔálʔal housing development, the Lushootseed word for "home," Feb. 3, 2022, in Seattle. Designer Johnpaul Jones is Choctaw. (Jovelle Tamayo for Crosscut)

Healing begins with housing

Of the 80 housing units, 10 are reserved for veterans. The focus on housing for Indigenous people was important because while American Indian or Alaskan Native individuals make up just 1% of the King County population, according to U.S. census estimates, they made up 15% of the homeless population in 2020. Indigenous people consistently experience homelessness at high rates. This is further compounded for Native veterans. “This really ensures that we're going to always keep an eye on our veterans in our community,” said Belgarde.

Sixteen other units are designated for double occupancy, and are a little larger to accommodate couples, elders and others who have caretakers. Fourteen units are Americans with Disabilities Act accessible, and eight others can be converted, but every room includes additional safety features for the stovetop, oven and heating. With mental health in mind, large windows were intentionally installed in each room to allow as much sun as possible to shine in. The rooms are furnished with a new bed, table and chairs, and Chief Seattle Club provided welcome kits with the necessary kitchenware and cleaning supplies so residents can prepare their own meals

The former executive director of Chief Seattle Club, Colleen Echohawk, is now the CEO of Eighth Generation, a design and lifestyle company owned by the Snoqualmie Tribe. She had gifts of wool blankets and Eight Generation coffee mugs brought to each room to welcome up to 96 residents into their new homes.

Belgarde believes that housing is just the beginning of true healing for Indigenous people. Having a stable place to sleep and a community that cares is an important step, but it doesn’t address the issues and trauma that resulted in their recent circumstances. Until just over 40 years ago, traditional Indigenous spirituality and cultural ways were illegal to practice in the U.S., which is what Indigenous people would have turned to for healing after the historical trauma of mass genocide from colonization, according to Belgarde.

Because Indigenous people were denied the right of freedom to believe, express and exercise the traditional religious rights and cultural practices, they were unable to heal. Belgarde has said this trauma was compounded by the Termination Act of 1953, which sought to disband tribes, sell their land and relocate them to urban areas, where they were promised housing, job training and prosperity, but were trapped into poverty with no social network, no community and nothing to fall back on.

Belgarde’s father, his family and so many others became urban Indians because of the Termination Act. The fallout of these laws still impacts Indigenous people today. Indigenous people have the highest poverty rate of any racialized group in the country. In King County alone, Indigenous people represent 30% of those experiencing chronic homelessness.

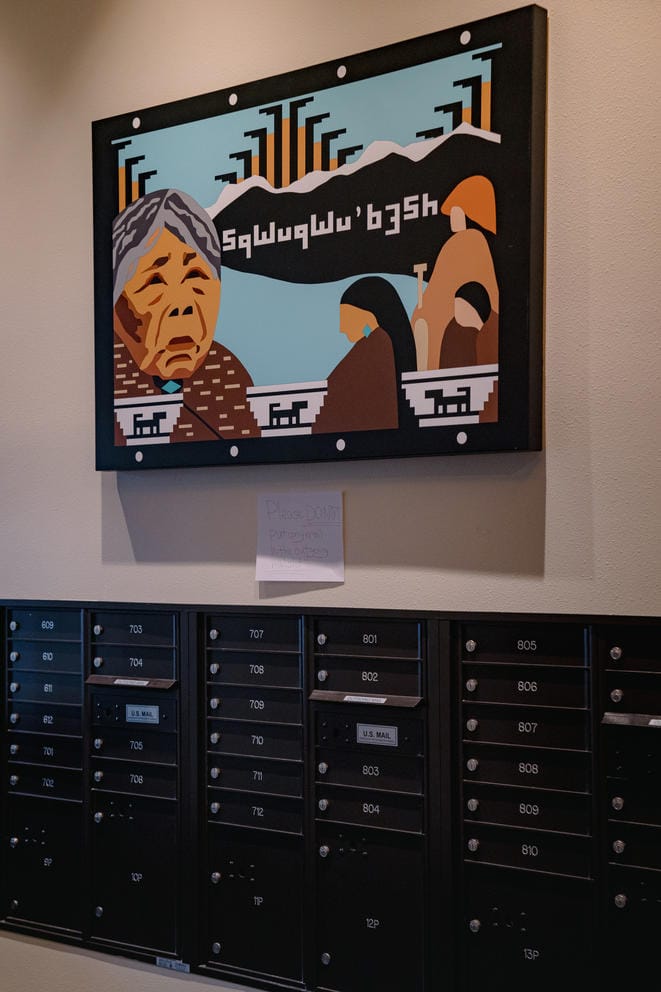

An artwork by Denise Emerson, who is Skokomish and Dine, sits over mailboxes at the newly opened ʔálʔal housing development, Feb. 3, 2022, in Seattle. (Jovelle Tamayo for Crosscut)

A sacred space

Tailored, culturally appropriate, trauma-informed services are crucial to true healing for Indigenous people, according to Belgarde. Staff and member’s shared experiences allow Chief Seattle Club to make policies, system changes and roll out services that serve nearly half of the 574 diverse federally recognized tribes throughout the country with varied customs and cultures.

Chief Seattle Club, a nonprofit dedicated to providing a “sacred space to nurture, affirm, and strengthen the spirit of urban Native people,'' opened in 1970 and has been serving Seattle’s growing population of Indigenous people experiencing homelessness ever since. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, its Pioneer Square Day Center served breakfast and lunch, offered showers and provided a laundry and mail service, job training and even a gathering circle — a traditional Indigenous form of group therapy.

More than anything the Day Center has given the urban Natives a sense of belonging. “I just love the community out here, the connections,” said Martin Spotted Bear (Blackfeet Nation). “It makes me proud to be a Native.”

“The laughter you hear, the stories, just people coming together, it's just really beautiful,” said Belgarde. “I can't wait to get back there.” The Day Center’s services are limited right now because of the pandemic and a remodel.

These familial community bonds are what Belgarde hopes to duplicate at ?ál?al. A major part of creating that community was “Indigenizing” the space, according to Belgarde. Anywhere you stand in the Day Center there is Native art. The intentional representation and atmosphere were meant to help make their members feel at home, “just like if you're in the auntie's house,” Belgarde said.

A unit in the ʔálʔal housing development, Feb. 3, 2022, in Seattle. Lifestyle brand Eighth Generation donated goods to the housing development, including the blanket seen here. (Jovelle Tamayo for Crosscut)

Shared experiences

That familiarity was important for people like Spotted Bear, who grew up on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana. Spotted Bear suffered from addiction and was living on his cousin's couch until he came to Chief Seattle Club. He received housing and job support and will be attending Wellbriety meetings, the Indigenized version of Alcoholics Anonymous that incorporates sweetgrass and traditional talking and drum circles. “It's good medicine,” Spotted Bear said. “It’s good healing.”

This model was applied to ?ál?al right next door. A gallery of Native art from a diverse range of tribes is represented within a few steps from every unit door and down each hallway.

Native art is just one step of many that Chief Seattle Club has taken to make ?ál?al a sacred healing space. Through Indigenous ways of knowing and thinking about healing, Chief Seattle Club created a home for Seattle’s Indigenous population struggling with homelessness by holistically caring for mind, body and spirit.

Belgarde understands the importance shared experiences make in building trust and accepting support because he experienced homelessness and struggled with addiction himself. Due to his distrust in the systems, he wouldn't seek support or stay in any of the local shelters.

“To live without hope, to just give up on yourself, give up on the idea that you can have anything better and just to be trudging along,” Belgarde said. “That is the worst feeling.”

His estranged wife suggested he check out Chief Seattle Club, where he found community in shared experiences and felt safe enough to receive the care he needed. “It really felt like home,” Belgarde said. “A place where I could be safe, not judged. Even those that I knew weren't active alcoholics or addicts, like the staff. I knew they weren't judging me. I knew that they had love. I could see it. I felt right at home.”

Belgarde moved on and went back to school to get his master's degree in public administration and then started working as the program manager at El Centro de la Raza. It wasn’t until a position opened up and his wife suggested he apply that he found his way back to Chief Seattle Club. Belgarde believes the Creator is working in ways that allow him to be where he is supposed to be.

Chief Seattle Club Executive Director Derrick Belgarde shows a unit within the ʔálʔal housing development, Feb. 3, 2022, in Seattle. (Jovelle Tamayo for Crosscut)

A model for the future

Lovell believes these shared experiences are what leads the nonprofit’s Indigenous members to open up to the case managers who connect them to mental health and domestic violence support, eviction prevention and more.

The ground floor of ?ál?al connects to the Chief Seattle Day Center. where members come for services. Case managers will be able to meet folks at the Day Center and make connections until members become comfortable enough to be guided to ?ál?al, where they will be able to speak with their case managers one on one in “talking rooms.”

“Sometimes it's these little margins that are so critical, like having a private space to talk,” Lovell said. “That's where you're going to say, ‘I don't do well with mental health.’ ”

A Seattle Indian Health Board nurse or minor care expert will also be at the Day Center, getting to know folks as a way to connect members to the clinic at ?ál?al, which will provide medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral health and traditional medicine services.

Indigeous people die at higher rates of preventable diseases like diabetes and suicide and have a shorter life expectancy than any other racialized group in the U.S. So having the clinic in the building was especially important to Chief Seattle Club leadership. “Having someone from the health board here get to know them, talk to them, I think that's gonna make a big difference,” Lovell said.

?ál?al is the first of many big plans for the Chief Seattle Club. There are plans for a 125-unit permanent housing project in Lake City called Sacred Medicine House. It will also provide wraparound services tailored for Indigenous people experiencing homelessness with the addition of traditional longhouses on-site for community gatherings and ceremonies.

Belgarde hopes to help other cities duplicate this model in the future.

“When I talk about stabilizing our community, I don't mean Seattle, I mean throughout the country,” Belgarde said. “So we have a lot of work to do, not just to build houses in Seattle. Our community is suffering in all these cities throughout the country.”